More Strong Shocks Likely, Scientists Say

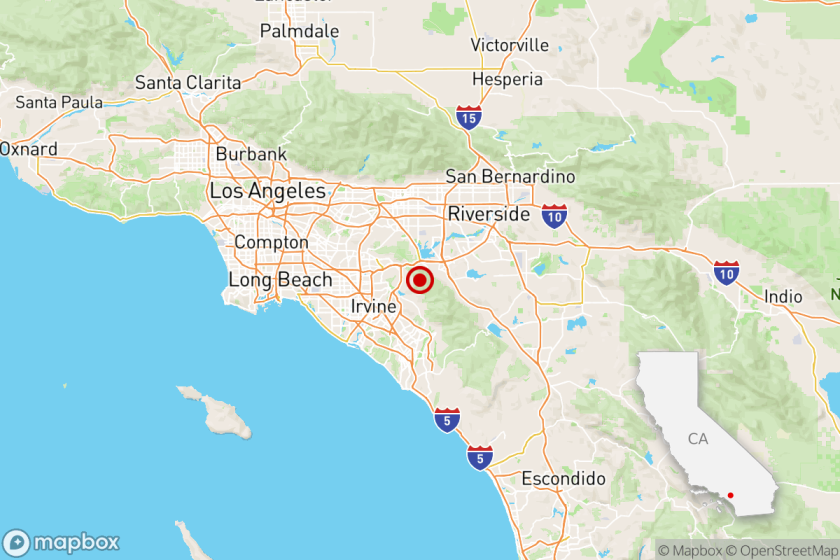

The U.S. Geological Survey warned Sunday that the “aftershock sequence (that) has developed just east of Los Angeles” after Thursday’s 6.1 earthquake “is likely to extend over several days and possibly weeks.”

Eight hours after Sunday morning’s strong aftershock, the Reston, Va.-based agency issued a statement which, in part, said:

“Individual earthquakes in this sequence may (continue to) cause moderate to strong, widely felt ground shaking, similar to that experienced Sunday morning. This shaking may in turn cause some additional damage, particularly in already weakened structures.”

Aftershocks, the statement noted, are a common occurrence after a sizable earthquake, and are caused by strain and instabilities introduced in the Earth’s crust by the main shock.

The Survey cautioned that “it is impossible to predict when aftershocks will occur.”

But, the agency said, it would not be unusual for an earthquake of magnitude 6 to be followed by more than one aftershock in the magnitude 5 range and many of magnitude 4 or less. It added that they tend to decrease in magnitude and frequency with time.

Sunday morning’s aftershock registered 5.5 on the Richter scale at Caltech’s seismology lab. The Survey’s earthquake center in Golden, Colo., put it at 5.3. Often, distance and varying interpretations of preliminary readings lead to different assessments of quake strength by seismological stations.

Despite the assurance in the statement that such aftershocks as Sunday’s are common, the agency’s senior seismologist in the Los Angeles area, Lucille Jones, said the actual timing of aftershock activity subsequent to Thursday’s quake has been “extremely abnormal.”

Release of Energy

“The average energy release after the main shock is usually a significant fraction of the energy of that shock, perhaps a third to a half,” Jones explained in an interview. “Up until (Sunday) morning, in this quake it had been 1% or less. That’s really strange.”

Sunday’s aftershock, she added, coming after two and a half days without many aftershocks, caused her to feel “somewhat relieved,” because “the energy release is now somewhere in the normal range.

“There may now be more aftershocks,” she said. “We can’t predict, but we would expect to continue to have aftershocks, perhaps moderately large, that will do damage.”

Generally concurring in this assessment was Caltech seismologist Kate Hutton, who said, “It’s certain that we can have more aftershocks in the 3 and even 4 range, and we can’t rule out those in the 5 range.”

Hutton said prudent Los Angeles area residents “will be very wary of damaged buildings and be careful dealing with bookcases” in coming days.

Meanwhile, as teams of government and private quake experts continued to investigate Thursday’s temblor and its aftermath, Jones said that a horizontal fault--of a type that has only in the last 10 to 15 years come to be appreciated by seismologists--may have been responsible.

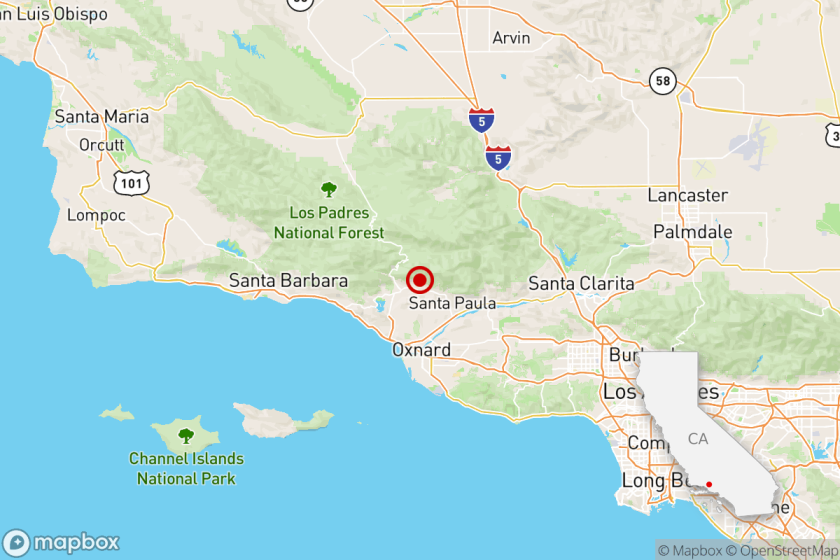

“These earthquakes have been off the end of the Whittier Fault,” Jones said. “Perhaps the most we can safely say is that they are in the Whittier Fault zone.”

Thrust From Beneath

Unlike the known, vertical orientation of the Whittier Fault and other mapped faults in the Los Angeles area, the slippage in Thursday’s main shock and Sunday’s aftershock was not so much a noticeable offset on different sides of a surface fault line as it was an up-and-down thrust from a shallowly dipping plane extending well beneath ground surfaces, Jones said.

According to this scenario, the land to the south and southeast of epicenters of the quakes of the last several days, such as the area of Whittier and the Puente Hills, was thrust upward, while areas to the north and west, such as Alhambra and Pasadena, may have sunk.

Jones said that such thrusts occurring in the distant past may have been responsible for building hills, known as anticlines, in the vicinity of the present quake activity. One such anticline, she said, is the low hill line extending west from Monterey Park into Los Angeles, a few miles west of the recent quakes.

Caltech was reported Sunday to have a graduate student’s paper on file that shows small anticlines developing in the immediate vicinity of the Rosemead, South El Monte, San Gabriel and Temple City epicenters of the main shock and various aftershocks.

Link to Earlier Quakes

Jones said that seismologists have concluded that similar horizontal or shallowly dipping faults were responsible for the 1983 Coalinga quake and the 1971 Sylmar quake.

Discovering and mapping such horizontal fault lines may greatly complicate the work of seismologists and others trying to assess earthquake risks, particularly in populated areas, according to experts who have recently become more aware of the importance of such faults.

For instance, Jerry Eaton, a USGS research seismologist at the agency’s Menlo Park office, said over the weekend that it used to be considered adequate if all observable faults were mapped along their lines of surface rupture. In the light of what is coming to be known, he said, costly additional research will now be mandatory to see what is going on underneath the Earth miles from the surface faults.

Jones said Sunday that the main shock and aftershocks this last week in the San Gabriel Valley have occurred six to eight miles underneath sediments where no faults have been mapped.

“Who really knows what the fault structure is there?” she asked. “We are going to have to examine ground water barriers and other kinds of phenomena before we can determine the seismicity of that region.”

As for some reports by Whittier homeowners that they have observed surface ruptures, Jones discounted these. She said that small cracks are not a conclusive sign of surface offset necessary to conclude that the traditionally known vertical faults have been responsible for the temblors of recent days.

More to Read

More to Read

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.