A Matter of Getting Us Covered : Insurance: Preventive measures now could help reduce losses in earthquakes and make California homes and businesses more insurable.

The specter of earthquake insurance will no doubt be raised soon in Sacramento.

There will be calls for California’s insurance companies to assume more responsibility for the staggering losses from the San Francisco Bay Area quake. Legally, the insurers probably won’t have to. Only about 15% to 20% of Californians have earthquake insurance. Those that have fire but not earthquake coverage may be out of luck, even if their homes burned down because of gas leaking from temblor-broken gas mains.

California insurers have generally resisted earthquake insurance. While such a policy might seem the epitome of corporate greed in an earthquake-prone state, it’s not hard to understand the reasoning. You see, insurers are in the business of investment, risk assessment and yield. And they like predictability. In other words, they like to insure sure things.

When assessing risks, the closest insurers can get to sure things is to employ the law of large numbers. The Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences describes this law as “a probability as a strong limit of relative frequencies.” In other words, if enough occurrences of a loss-causing event can be found in history, one can predict the number for a future period with reasonable accuracy.

Not only do insurers want to know how many loss-causing events will occur, but also how severe they will be. Insurers refer to this as “exposure,” or incidence times severity.

Some types of exposure are easier to predict than others. The less predictable perils--like earthquakes--are another story. We have a lot of information about earthquakes. But we still don’t do a good job of predicting their occurrence, magnitude and intensity.

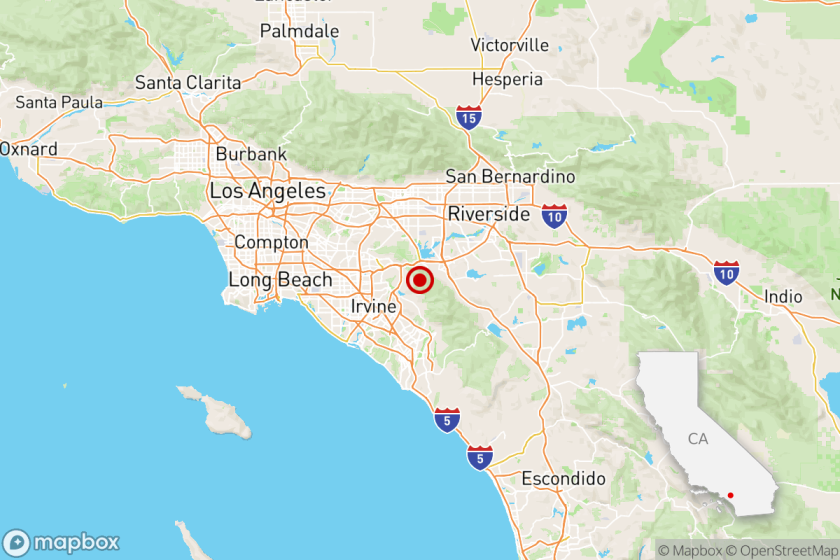

Seismologists tell us that there will be a major earthquake in the Los Angeles area within 30 years. By major, they mean 8.25 magnitude, or many times the intensity of the 7.1 quake that hit the Bay Area. There is no disagreement that the destruction would be unimaginable. Distribution of the losses would vary, depending on the time and day of week that the quake struck. There would be life, automobile, fire, health and accident claims in any case, and if the temblor occurred during a work day, more workers’ compensation claims. Damages exceeding $50 billion is the estimate that I hear most, an amount that would exhaust all resources of California’s insurance companies.

Still, California insurers probably won’t have to pay for last week’s earthquake-caused property damages unless policyholders have specific earthquake coverage. The antecedents of that fact go all the way back to the Great Quake of 1906. In that disaster, a heating and ventilating shop was destroyed--not by shaking, but by a fire that was moving from building to building. The shop owner had fire insurance so he filed a claim for damages. His insurer denied the claim since the fire was caused by earthquake. They went to court.

The case made its way to the California Supreme Court, which in effect said to the insurer, “you wrote the policy, so you should have said that you wouldn’t cover fire damage after an earthquake.” The court relied on a longstanding principle that contracts should be construed against the drafter.

Over the years, the reasoning of this case grew into the doctrine of concurrent causation. In simple terms, this is the idea that if a loss has two causes--one covered by insurance, the other not--the insurance should cover the loss.

From an insurer’s point of view, it’s easy to see why the doctrine of concurrent causation could foul up your expectations. The problem erupted again after the Coalinga quake of 1983. Many of the victims didn’t have earthquake insurance but they looked to their insurers for what they believed their policies covered. The insurers initially balked at paying. When they eventually gave in, they also went to the Legislature for future protection from concurrent causation and a requirement that they offer earthquake insurance. And now, according to a reading of the legislation, if you don’t have any earthquake coverage, the insurer has no obligation to cover you.

In these days following the Bay Area quake, expecting the Legislature to unilaterally force insurance companies to absorb earthquake losses is unrealistic, both from a financial and political perspective. But we can use the impetus of this latest disaster to better equip ourselves against the next earthquake, and in doing so, create a more reasonable risk for insurers to shoulder.

Specifically, we can begin to view our state as the Japanese view their volatile island nation. Just as we severely limit development in floodplains, the Japanese restrict construction on the types of land that have been shown to be especially unstable during earthquakes. We can also begin to retrofit structures that don’t meet current earthquake standards.

We still don’t know when or where the Big One is going to hit. But isn’t this as good a time as any to try to cut our losses? The more we do, the more acceptable the risks will be to insurers and they can begin to act like insurers. Preventive work done before an earthquake is expensive, but it’s much less costly than what comes after.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.