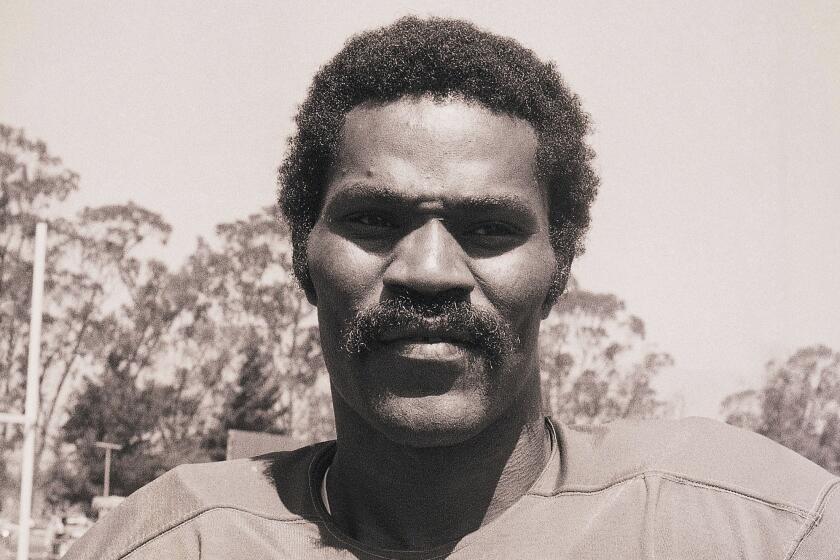

Fires: First to Lead, and Often to Finish

The starting gate sprung open and a horse named Pull the Lever seemed to explode out of it in a recent race at Gulfstream Park. His rider was pushing with his hands and arms, vigorously and rhythmically, then cracked the horse twice with his whip. Jockey Earlie Fires wanted to be in front, as usual.

One of his rivals, Manuel Santos, had the same idea. He was driving his mount, Always Beige, to get the lead, and the two horses sped away from the field at a suicidal pace. If they went much farther at this rate, they would both collapse, long before the 1 1/16th-mile race was over.

It was a classic game of brinksmanship, one that Fires has played thousands of times before.

“You see if you can take the play away from the other horses,” he says. He wasn’t going to back off. If one could have read Santos’s mind at this moment, he was probably thinking: “This madman is going to destroy us both.” Almost imperceptibly he took a tighter hold on Always Beige, easing him back. And Pull the Lever suddenly was in front by himself.

Now that he had secured a clear lead, Fires could permit his mount to relax. Pull the Lever wasn’t challenged again, winning by four lengths.

By most standards, this was an ordinary race won by an ordinary horse; even Fires barely remembered it when he was asked about it a few days later. Yet it was also a classic illustration of the role of raw speed in American racing.

Every fan and bettor appreciates the importance of speed. No type of horse is more formidable than a front-runner who takes an uncontested early lead. Conversely, no type of horse is vulnerable to more forms of misfortune than one who tries to come from far behind.

The only members of the racing community who seem oblivious to these axioms are the jockeys. Most riders are reluctant to make all-out efforts to use their horses’ speed--perhaps because they know they will be second-guessed (or fired) by the trainer if the tactics fail. So bettors are constantly cursing jockeys for being too patient, too passive, too cute, too clever when they fail to go to the front with a horse who ought to be there.

That’s why serious horseplayers love to watch and bet on Earlie Fires. They know he will come out of the gate in high gear; if his horse loses, he’ll go down fighting.

Casual fans might think that such a strategy is too simplistic to get results, but Fires’ whole life is a testimony to the efficacy of speed. When he led all the way to win the last race here Wednesday, it was the 4,841st victory of his career. He ranks 11th on the all-time race-winning list, one position below Chris McCarron and a couple of spots ahead of Eddie Arcaro. At age 43 he still looks so robust and powerful that he is going to win many more before his career is over.

Fires’s style doesn’t stem from any philosophical conviction about the importance of speed. Instead, he said, “Basically, I always ride a horse the way the trainer wants. I started riding at a bush track, Miles Park, and if you got the lead there you’d have a big edge. You’d ride all-out from the start, and I’ve always ridden that way.”

Fires gained a reputation as a “speed rider,” the successor to the great front-running jockeys of the last generation, Bobby Ussery and Walter Blum. And the reputation became self-fulfilling.

“When people ride me,” Fires said, “they usually tell me to put the horse on the lead. That’s what they want.”

While the reputation has helped him enjoy nearly 25 years of success, it has worked against him, too, for trainers and owners don’t want a supposedly one-dimensional jockey riding for them in big stakes races.

The last top-class horse for whom Fires was the regular jockey was In Reality--in 1966. That is why, even after 4,841 victories, he is little-known outside of Florida, Kentucky and Illinois, where he does most of his riding.

Moreover, Fires’ special talents are ones that are too easily taken for granted. When jockeys gun their horses to the front, racing fans tend to think it is a matter of will rather than skill.

But Blum, a Hall-of-Fame rider who is now a steward at Gulfstream, says, “There’s a real knack to getting a horse away from the gate quickly, and Earlie happens to be an exceptional gate rider. He transmits a certain calmness to the horses so they’re not fidgety in the gate. He makes them stand with their four feet solidly on the ground and their head straight. That’s why they’re so quick to get in stride.”

Fires couldn’t have found a better showcase for his skills than Gulfstream Park this winter. The track has been highly speed-favoring for most of the season. The riding colony is populated by big-name New York jockeys like Richard Migliore, Randy Romero and Jean Cruguet, who almost never gun their horses from the gate. (When the agent for a New York rider was upbraided because of his rider’s reluctance to go to the front aggressively, he replied, haughtily, “We don’t ride that way in New York.”)

This passive group has constituted a perfect foil for Fires, and he is the leading rider at Gulfstream this winter. His success demonstrates that, for jockeys at least, good things happen to those who don’t wait.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.