Low-Key Approach Keeps Search Organizer on Top of Rescue Missions

After lurching down snowy trails and ducking 100-m.p.h. gusts of wind for two days, a member of the Sierra Madre Search and Rescue Team at last came upon a pair of missing hikers huddled in the snow below the Mt. Baldy summit.

The searcher couldn’t restrain himself. “We’re with them!” he shouted into his walkie-talkie. “We’re with them!”

But if he had expected an effusive response from Arnold Gaffrey, manning a search command center down the mountain, he was out of luck.

“With who?” asked the ever-methodical, never-take-anything-for-granted Gaffrey, one of the state’s preeminent mountain search organizers.

That attitude--a world-wise understanding of the way things can get turned upside down in a snowy wilderness--can dump a lot of ice water on people’s emotions, Gaffrey’s colleagues say. But it’s precisely what is wanted in a person running a search-and-rescue operation.

“It takes somebody with a real dogged determination to maintain objectivity,” said fellow team member George Duffy, a U.S. Forest Service ranger.

Few operations leaders are as enduringly objective as Arnold Gaffrey, the team’s low-key planning ace, whom colleagues good-naturedly refer to as “Spock.”

“Arnold approaches it with the old Yogi Berra thing of ‘It ain’t over ‘til it’s over,’ ” said Duffy. “He doesn’t anticipate the success of the search and thereby limit his thinking. He’s a wizard.”

The Sierra Madre team, one of the nation’s most innovative mountain rescue teams, has been plying the slide-prone slopes of the San Gabriel Mountains for 40 years. Team members were the first to use helicopters as rappelling platforms, sliding down ropes to inaccessible wilderness locales, and the first to attach a rubber wheel to a wire stretcher, turning it into a kind of labor-saving wheelbarrow for the injured.

The team’s 18 volunteers have joined searches in the High Sierra and Baja California. But mostly they pry fall victims off the rocks in the team’s own back yard or spend long, frustrating hours scouring the forest between Mt. Wilson and Mt. Baldy for errant hikers. The Angeles National Forest is, for all of its dangers, a playground for about 27 million, often ill-prepared visitors a year.

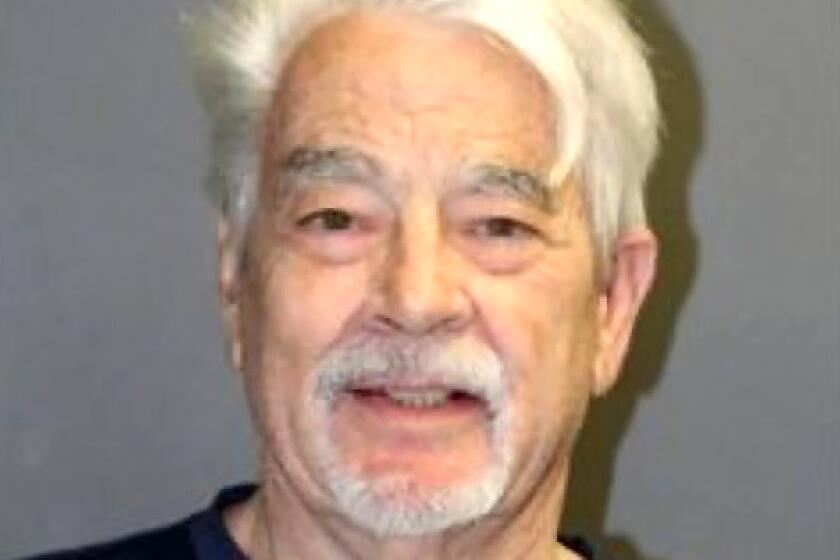

Gaffrey, 40, a thin, graying man who instinctively dodges the spotlight, has been in the thick of it for 19 years. He has done his share of traipsing up and down steep, boulder-strewn slopes, leading lost Boy Scouts back to civilization and transporting climbers with broken limbs to hospitals.

But as often as not nowadays, it’s Gaffrey in the team’s communications van, dividing maps into sectors, keeping track of the searchers in the field, summoning helicopters or bloodhounds or reinforcements on the van’s nine shortwave radios and--like an experienced chess player--planning the next series of moves.

“You’re a sort of coordination point between where the city stops and where the mountain starts,” said Gaffrey, an insurance agent in Sierra Madre.

The idea is to run “surgical searches,” he said, paring down the search area to the narrowest possible swath on a map before the team even gets into the field.

Gaffrey knows his turf, fellow team members said. But perhaps more important, he’s an instinctive diplomat, using that unexcitable personality to establish trust between the team and the public agencies with the big resources.

“Say you want to secure some helicopters,” said team member Phil Lester. “Go through channels and you get into the typical paper trail and, you know, 400 phone calls. But Arnold knows who to call directly.”

A member of a rescue team can expect to be rousted out of bed at least eight or 10 times a year to go stumbling along dark, treacherous trails, for no recompense. An understanding employer and, usually, a long-suffering spouse are necessary.

Gaffrey’s wife, Gail, said she has gotten used to the late-night calls.

“A lot of times he doesn’t leave right away, but mentally he’s gone immediately,” she said. “He gets so pumped up, getting it all planned, looking at maps, that he can’t sleep. I just tune it out to a degree. I know he’s gone.”

“Arnold’s usually the single person who’s most concerned about the victim,” said Steve Millenbach, the president of the team. “He’s not into ego trips.”

For Gaffrey, the idea of a rescue effort as a big collective effort, with individuals subsuming themselves into the whole, is almost a religion.

Ask him if he’s proud that, out of a search party of 70, his own team was the one to find those lost hikers early this month on Mt. Baldy. “Not really.” he said. “Everybody who took part did it. There were all these other assignments that people had to do, and if they hadn’t, our guys never would have gotten to the victims. I really believe that.”

Why has he persisted for 19 years? Gaffrey flounders for a minute. “I should really have an answer,” he says. “I guess it’s because humans are bred to help each other. This is my way of satisfying that need.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.