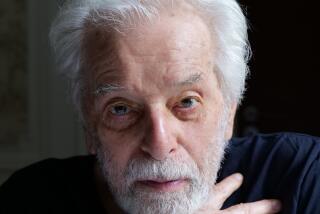

Golijov, steeped in a tale of Lorca

Three years ago, Osvaldo Golijov’s scorching setting of St. Mark’s Gospel, “La Pasion Segun San Marcos,” made him a new-music star, but only now has he written another large-scale score. On Sunday night, the Tanglewood Music Center -- the teaching wing of the Boston Symphony’s summer home in the Berkshires -- premiered “Ainadamar,” Golijov’s first opera.

Given the added attractions of a libretto by popular playwright David Henry Hwang (“M. Butterfly” and the recent updating of “Flower Drum Song”) and a leading role written for soprano Dawn Upshaw, the sold-out, steamy old 700-seat theater at the center seemed to be bursting at the seams with members of the musical. New York and Los Angeles have already gotten into the act. The 70-minute opera was given in a co-production with Lincoln Center, the Brooklyn Academy of Music and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, which will stage “Ainadamar” at Walt Disney Concert Hall in February.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. Aug. 13, 2003 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Wednesday August 13, 2003 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 1 inches; 40 words Type of Material: Correction

Britten opera -- A review from the Tanglewood Music Center in Massachusetts in Tuesday’s Calendar mistakenly said that Benjamin Britten’s opera “Peter Grimes” was commissioned by Tanglewood “nearly half a century ago.” In fact, it premiered there in August 1946.

There is no getting around Golijov’s appeal. When the Argentine-born composer, who lives in the Boston area, came onstage for his curtain call, he received a rapt, standing ovation. The opera does, indeed, contain beguiling, original, moving, memorable music. But the fact that his work could prove winning despite an inept production and a mediocre libretto makes Golijov seem only that much more a phenomenon.

“Ainadamar” was presented on a double bill with another new opera, “Rage d’Amours,” by the young Dutch composer Robert Zuidam. Zuidam and Golijov studied at Tanglewood in the late ‘80s and have maintained a close connection with the center since. And making these premieres all the more intriguing, this is only the second time Tanglewood has commissioned an opera. The first, nearly half a century ago, was Benjamin Britten’s “Peter Grimes.”

Something strange happened with the new commission. Two composers from very different cultures and with very different musical styles independently found their subjects in Spanish history and set their operas in Granada. “Rage d’Amours” deals with the mad, sexually obsessed Spanish queen known as Juana La Loca. “Ainadamar” concerns the great Granadan poet and playwright Federico Garcia Lorca and his execution in 1936 by the fascists at Ainadamar, the Fountain of Tears, during the Spanish Civil War.

More specifically, “Ainadamar” revolves around the actress Margarita Xirgu and Lorca’s play “Mariana Pineda,” about the early 19th century Granadan heroine who conspired to overthrow Spain’s tyrannical King Fernando VII. The opera begins with Xirgu, who had created the role of Pineda, looking back on her life, wishing she could have saved Lorca: Had he accepted an invitation to tour South America with her, he would not have been captured. A younger Margarita appears in flashback scenes with Lorca, while the older Margarita looks on, observes and interacts (the same device used in Bright Sheng’s opera “Madame Mao,” which had its premiere two weeks earlier in Santa Fe, N.M.).

Lorca, who is portrayed by a mezzo-soprano (an allusion to Lorca’s bisexuality, perhaps?), comes back from the dead, and the three women sing an ecstatic, Straussian trio. The opera ends with old Margarita dying on stage, only to rise again and be joined once more by Lorca. The stage darkens, and their clasped hands are illuminated, through a Robert Wilson-like effect, in a square of light.

Hwang’s contrived libretto, originally written in English and then translated into Spanish by the composer, does have the advantage of allowing for chunks of unadulterated Lorca to be included. The text of Margarita’s final aria is taken from “Mariana Pineda,” as are lines sung by a small women’s chorus at the beginning of each of the opera’s three sections.

The score is more subdued and less varied than “Marco,” influenced more by Spanish music, particularly flamenco, than South American. It is full of stunning things. The vocal writing is passionate, and Upshaw, as the older Margarita, sang the role rivetingly. The student cast was excellent, particularly mezzo Kelley O’Connor as Lorca.

Although balances between stage and pit need further work, Golijov’s orchestral writing is often special. The rhythmic groove in the bass, the dancing distant trumpet lines and the intensely expressive wind solos were just a few of the things that carried this gratified listener along. Robert Spano conducted with graceful enthusiasm, and the student orchestra played with considerable refinement, if not quite enough abandon.

The production team looked impressive on paper. Chay Yew has close ties to the Mark Taper Forum and the East West Players. Ostling did the sets for Mary Zimmerman’s “Metamorphosis”; Anita Yavich, the costumes for many fine Francesca Zambello opera productions.

Yet staged on a nonrealistic set consisting of a raised platform but with conventional costumes, the production proved the worst of both abstraction and tradition. This is the only time I can recall Upshaw being theatrically unconvincing; she was forced to rely on cliched, clenching gestures. And then there was the dancer wearing a sculpted horse head. She kept popping up as if Martha Graham were getting a free ride back from the dead along with Lorca.

“Rage d’Amours” will not accompany “Ainadamar” to New York or L.A., and there is no reason it should. This time, the central role was divided among not two but three sopranos, one of whom was the wonderful Lucy Shelton. Here, though, the main attraction was Zuidam’s sinuous instrumental writing, which sounded like early music that had gone through modern spectral shifts; it was very well-conducted by Stefan Asbury. But it was also unchanging, and the libretto, written by the composer in French, was far too reductive to make much of its intended shocking sexual allusions. The production team took a more realistic approach than in “Ainadamar,” but it was no more effective.

Undoubtedly, there are better operas than these in Zuidam and, especially, Golijov, and astute collaborators might have steered the composers in a more successful direction. I don’t know how much the L.A. Philharmonic has invested in the “Ainadamar” production, but I do know that it was not nearly enough. At this point, the Phil should think seriously about bringing in another director and creating a new production.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.