Success hasn’t spoiled skating champion

It’s barely 7 a.m., but the Pickwick Ice Center in Burbank is a maze of skaters, some so newly awake that pillowcase creases are still imprinted on their faces.

One girl in a pink-striped shirt and ponytail stands out. She soars toward the ceiling when she jumps and turns into a colorful blur when she spins, swift and sure and confident.

Just like a champion.

Which she is.

Mirai Nagasu is also a freshman at Arcadia High, and her mother, Ikuko, waits for her with a pink, monkey-patterned blanket and an anxious expression. Winning the U.S. figure skating title is no excuse for being late for school.

Nagasu, who will be 15 in April, is the second-youngest woman to win the U.S. championship, a stunning achievement in her senior-level debut.

She is everything this faltering sport could wish for: charming, unspoiled and tremendously talented. The daughter of Japanese immigrants who operate a small sushi restaurant, she’s the American dream in a 4-foot-11, barely 80-pound package.

Thanks to her victory, she’s also a celebrity among the kids at school. “They say I look tall on TV and then when I get off the ice, they say, ‘Wow, you’re so small,’ ” she said.

Not to worry. Nagasu stood tall atop the podium last month and will soon have another chance to rise above the pack.

Although she’s too young to compete at the senior World Championships, Nagasu will pursue the world junior title beginning Friday in Sofia, Bulgaria. She will be old enough for the big show next year, when it will be held in Los Angeles and could launch her toward the 2010 Vancouver Olympics.

“I haven’t really thought of it, but at nationals I had a glimpse of a thought because I saw myself on the poster,” she said of an advertisement that features her image. “The reason I noticed it was the person was wearing my dress. I was like, ‘That’s me!’ ”

No mere picture could capture the depth of her will. She looks delicate but is strong-minded enough to have succeeded in a sport that can be cut-throat and capricious, exhilarating one moment and heartbreaking the next.

Although she fell on the first jump of her free skate routine at the U.S. championships, she rebounded with spirit, skating with speed that her rivals can’t match as well as impressive technique.

“She’s extremely bright. She certainly has a determined streak,” said Bob Paul, one of her coaches for eight years. “She used to fall a lot and got over that fast.”

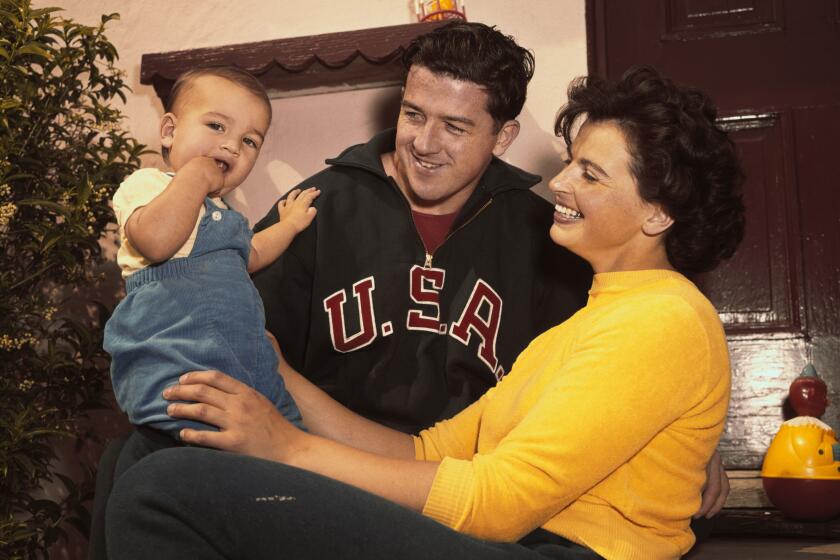

Paul has a singular perspective. An Olympic pairs gold medalist in 1960, he helped smooth and style the programs of medalists Peggy Fleming, Linda Fratianne and Dorothy Hamill, among others.

“They had that god-given talent,” he said. “But how many take that talent and follow through with it?”

Nagasu could be one of them, though it’s unfair to create such expectations so soon.

Countless kids who easily reeled off triple jumps when they were 13 have become has-beens at 16, undone by puberty and physical changes. It’s a treacherous time for any girl to navigate. Skaters navigate it publicly.

“No one can see into the future,” said Charlene Wong, Nagasu’s primary coach the last 18 months and formerly an elite-level skater for Canada. “It’s possible there still may be challenges as her body changes. It could be more empowering.”

Wong leads Nagasu’s team of five coaches and renowned choreographer Lori Nichol. Paul recommended Wong after seeing Nagasu repeatedly stumble at preliminary competitions. “The mental game is the whole game and it’s what Mirai didn’t have,” Paul said. “She didn’t get out of sectionals.”

Wong didn’t have to teach her to jump. Nagasu knew that.

“What had been lacking in her career was direction,” Wong said. “I still feel there’s a lot of learning to be done, but the results have been good so far, so I’m not complaining.”

Nagasu’s parents aren’t complaining either, another refreshing twist.

Ikuko and Kiyoto Nagasu aren’t crazed youth-sports parents. Nor are they looking for a meal ticket.

Ikuko won’t identify the family’s restaurant even though publicizing the name might make cash registers ring. Concerned for her only child’s safety after media reports that Mirai slept in a made-over closet in the restaurant, Ikuko said the arrangement has been changed but wouldn’t be more precise.

Ikuko politely declines interviews except to thank the skating community for its help -- Mirai has been aided by a skating foundation and patrons of her old rink in Pasadena -- and to say her daughter is “a regular kid” who makes the bed “not every day” but often enough.

“Mirai’s family are very private people,” Wong said. “I think her mother is shy, but from my understanding she feels this is her daughter’s time and there’s no need for her to share the limelight. . . .

“The way I like to put it is Mirai’s in the driver’s seat, Ikuko is in the passenger seat and I’m directing traffic.”

The signpost ahead points toward the 2010 Olympics. Nagasu would be 16, probably her prime. Three of the last four women’s gold medalists were teenagers: Oksana Baiul was 16 in 1994, Tara Lipinski was 15 in 1998 and Sarah Hughes was 16 in 2002.

“I certainly know she wants to be on the Olympic team,” Paul said. “But I think her family had no idea it was going to come this fast.”

Nagasu is driving in the fast lane, but she’s being smart.

“Right now I’m taking each thing step by step and trying to do my best at each competition,” she said, composed as always.

Whatever happens, may she always be this grounded and sane.

--

Helene Elliott can be reached at helene.elliott@latimes.com. To read previous columns by Elliott, go to latimes.com/elliott.

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.