A fence goes up to deter school shootings, and a neighborhood loses its park

Joaquin and Jude Perez, like many children in their Long Beach neighborhood, learned how to ride their bikes on the blacktop at Fremont Elementary School. The school grounds have long been their de facto park, where they play with friends after school and on weekends while parents chat.

But last week, Fremont Elementary parents were notified that the school would soon become a “closed campus.” New fences would secure the school and after-hours public access would be blocked. A few days ago, a school police officer asked 6-year-old Jude and his dad to leave while they were playing soccer with friends in the evening.

The new security measures are designed to keep campuses safe from violence in an era when protecting children from violence and mass shootings is a top priority, Long Beach Unified School District officials said. Fremont will join most of Long Beach’s 85 other campuses that are fenced in and require visitors to enter through a single front office door, often armed with a buzzer and camera.

“Some of our campuses have been fully enclosed for decades,” district spokesman Chris Eftychiou said in an email. “But two months after [the] Parkland [shooting in 2018], our school board voted to provide additional fencing so that we could fully enclose the remainder of our campuses.”

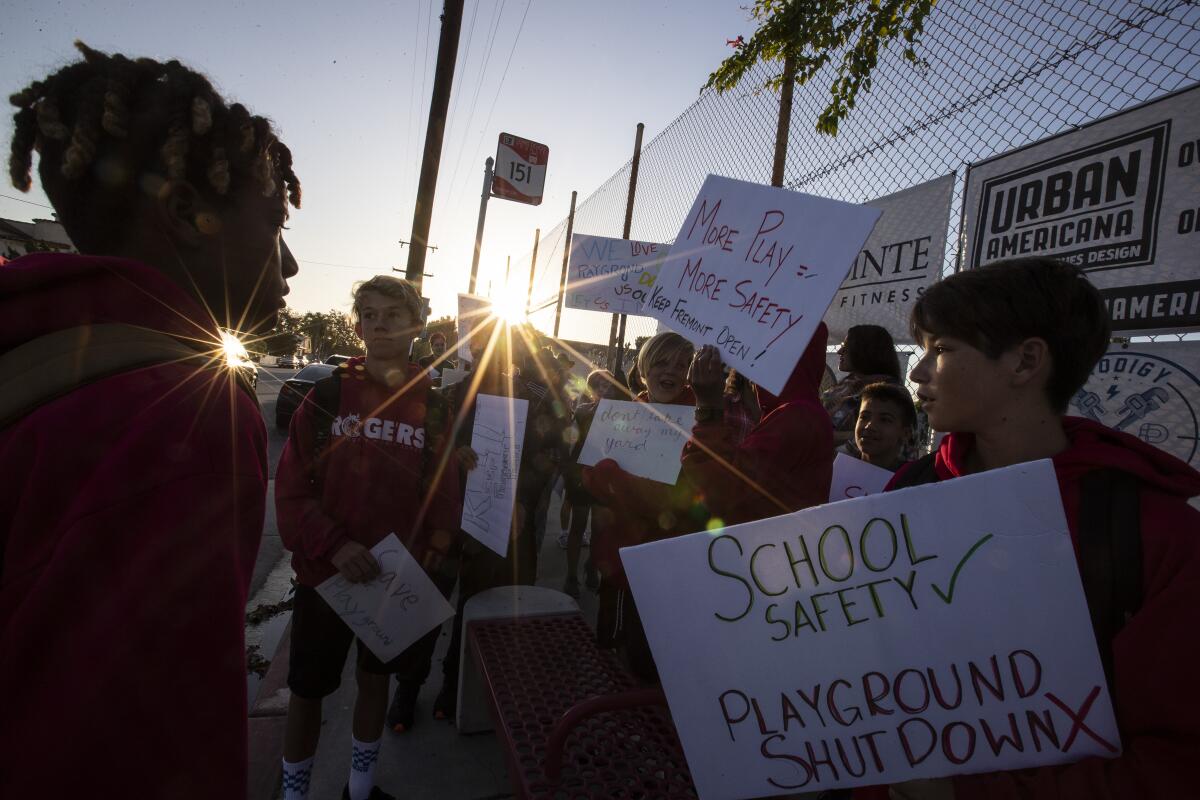

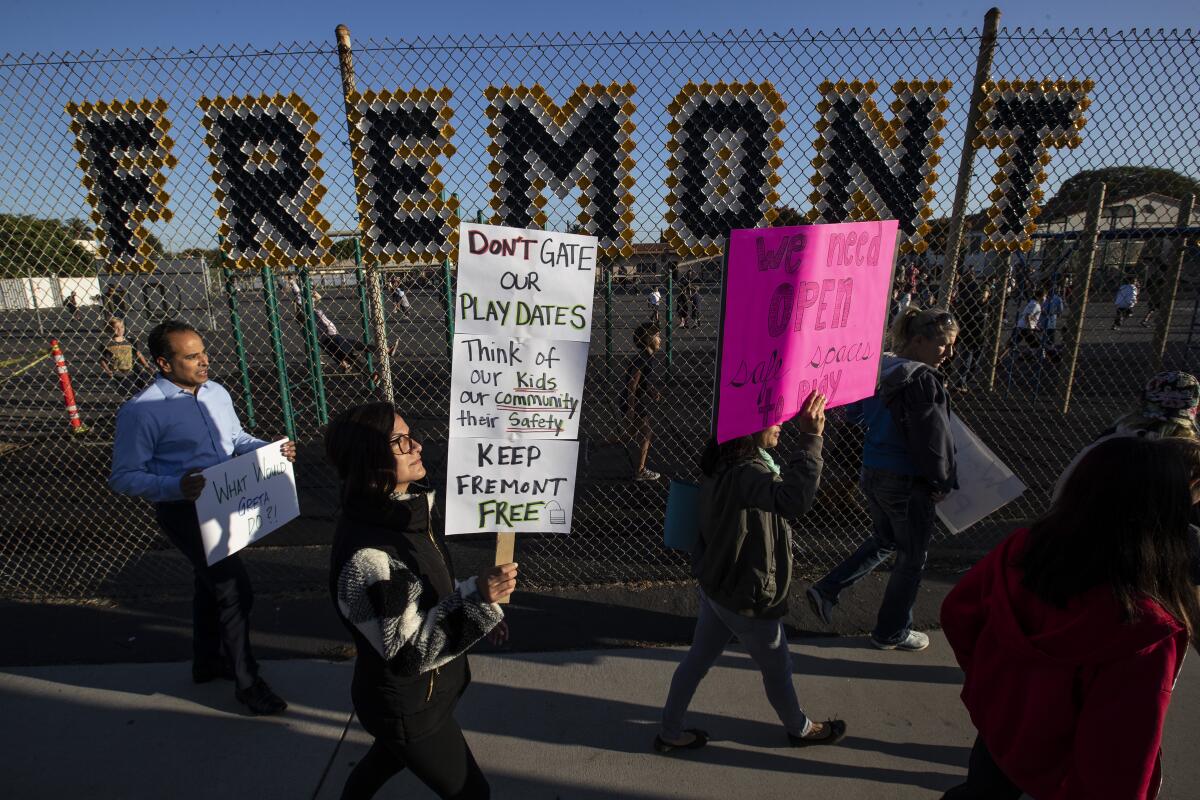

Many in the community, however, see the closed campus as a loss worthy of protest. Fremont offers the only large play area within walking distance of their homes.

On Wednesday, Perez and dozens of other parents, students and community members took to the streets, picketing in front of the school with signs that read “Keep Fremont Free” and “Save Our Fremont Community Playground.” They marched, chanting “Don’t fence us off” and “What do we want? Play space! When do we want it? Every day!”

The discord in Long Beach comes as two movements collide. School leaders are acting to address compelling safety issues, while public health researchers and community activists push for more open space for play and exercise and stronger neighborhood ties to campuses, especially in low-income neighborhoods.

Opening schools up to the neighborhood helps families feel comfortable and moves them to become involved, said Jeff Vincent, director of the Center for Cities and Schools at UC Berkeley, a policy research center focused on developing family-friendly cities centered on high-quality school access. But the “hardening of schools” that’s happening as a result of school safety initiatives post-Parkland might deter such involvement, he said.

“If you look at movements in education and school improvement … there’s been a focus on family connections and even community connections — that those things, when done well, raise achievement,” Vincent said. “So how do you have a hard or safe school from a shooter and yet still retain community connections and parents can sort of flow in and out?”

Across the country, in urban and rural school districts, educators and city officials are working to find ways to keep schools open on the weekends and after school, recognizing that safety is paramount.

In Los Angeles, Mayor Eric Garcetti committed to opening 25 community school parks by 2025 “to provide access to school yards over the weekends in neighborhoods where green space is not yet in walking distance from most families.”

Cities have come on board in part because it’s less expensive to take on some of the cost of keeping a school open than it is to build a park, said Cesar De La Vega, an analyst at Oakland-based ChangeLab Solutions, a public policy and health equity nonprofit.

Darla Nash, a Fremont parent, supports the district’s decision to enclose schools. In 2012, after the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School that killed 26 people, including 20 children, the community “said through tears they would do anything in their ability to protect their children,” Nash said. Her son, too, learned to ride a bike at Fremont, but she would rather have a school that’s always closed than one where officials have not done everything possible to secure the campus. Parents can take their kids to the park less than a mile away, she said.

But what about the kids whose parents work late or on the weekends, or don’t have bikes, or are too young to travel that far alone, countered Jyoti Nanda, a mother who was one of the protest organizers.

“They don’t have parents to drive them to Lagoon Park, they’re latchkey kids,” Nanda said.

Parks are least available per capita for African Americans, Latinos and low-income residents in L.A. County, according to a 2016 report from the county’s public health office. The kids of Fremont are not the most heavily affected by a lack of park access, but there is a need.

Fremont’s school community is mostly white and Latino, and about 1 in 5 students are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, a poverty marker. The school is nestled in a suburban neighborhood of single-story homes and small apartment complexes, many of which don’t have open space.

The Trust for Public Land rates Long Beach high in terms of access to parks — most residents of all races, age groups and income levels are within a 10-minute walk of a park, according to the nonprofit land protection organization. Part of the Belmont Heights neighborhood near Fremont, however, is rated as high need in the group’s 2019 analysis.

Fifth-grade Fremont teacher Kristal Cheek said she feels safer knowing that there will be one entrance to the school but also enjoys working on a campus where community members know one another and treat the school like a park.

“There’s two sides to it,” Cheek said. “I mean, there’s safety issues while we’re in school.”

Schools across the country have taken a similar approach to Long Beach since the shooting in Parkland, Fla., said Ken Trump, president of the consulting agency National School Safety and Security Services.

Many, especially in Florida, are erecting fences around campuses, installing buzzers and instituting a “single point of entry.” These might work for some schools. But Trump suggests investing in training front office staff and said there’s no safety reason related to mass shootings to block playground access during non-school hours.

“What’s your real drive here?” he asked. “Is it really security, or is it security theater?”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.