Wave goodbye: Long Beach breakwater won’t be removed

When Kelli Koller decided to open her Long Beach surf shop with a friend in late 2012, she knew it was a bit improbable in a city where the waves never rose more than a foot.

But her store reflected a sincere hope that rolling waves would finally return to the city’s 5½-mile shoreline.

At the time, Long Beach was swept up in a push to remove part of the 2.2-mile breakwater that hems in East San Pedro Bay, blocking any significant wave action. “Break the Breakwater” bumper stickers spread. Surfers talked about riding waves for the first time in five decades, restoring Long Beach’s moniker as the “Waikiki of Southern California.” Other advocates hoped more free-flowing surf would reduce poor water quality plaguing some local beaches.

Yet, over the years, efforts stalled amid studies and questions. Two years ago, Koller closed her Seventh Wave Surf Shop.

And now, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has concluded that any changes to the breakwater would be too costly and could hamper Navy operations there, as well as at the ports in Long Beach and Los Angeles, the oil islands and Long Beach’s Carnival Cruise terminal.

The agency used wave models to simulate how changes to the breakwater could affect existing infrastructure. The data showed that the oil islands — which were created to conceal offshore drilling operations — along with the Shoreline Marina and the port would all need additional armoring if the waves returned, officials with the corps said in an interview this week.

“We’ve been working on the analysis for some time,” said Raina Fulton, who oversees the corps’ project considerations. “We didn’t have complete answers based on data until recently, but we’ve had concerns all along.”

The agency instead proposed an initiative, dubbed the Reef Restoration Plan, to cultivate 201 acres of aquatic habitat with kelp beds, rocky reefs and eelgrass to improve water quality and support habitat biodiversity in East San Pedro Bay.

If agreed to by the Long Beach City Council and approved by Congress, the initiative would be the corps’ first open-ocean ecosystem restoration project in the nation, officials said.

The plan could be a model worldwide, experts say. The project “provides habitat for key life stages of a diverse population of fish and other aquatic species, primarily by providing foraging, sheltering and critical nursery functions that support population health and growth,” the study says.

The restoration plan is projected to cost nearly $141 million. The federal government’s share would be about $91.5 million, while Long Beach would be responsible for $49.3 million. Before anything is finalized, the corps is seeking feedback from the public on results of the study.

“It has to be a project that both entities can support to move forward,” City Manager Tom Modica said. “The city could select a plan that includes changes to the breakwater, but that would not be one the corps would support.”

The report included six options to improve the ecosystem along the coast: one that proposed no changes to the area, three that focused solely on restoration and two that included restoration efforts and removing parts of the breakwater to allow wave action.

One proposal with modifications to the breakwater included a process called notching, which removes two 1,000-foot sections in the middle of the barrier. Another option called for removing one-third of the eastern end of the breakwater. Those plans would cost $993 million or $670 million, respectively, according to the corps’ analysis.

Ultimately, the results of the study showed that modifying the breakwater — constructed in the 1940s in part to shelter the fleet of Navy ships that dock in Long Beach — would hurt naval operations, including activities in support of national security and other missions. The Navy operates an explosives anchorage used to transfer ammunition between vessels inside the breakwater. Those ships need calm water to conduct operations safely, according to the report.

“Because of its purpose as a strategic contingency asset, the anchorage must be available for use on short notice at any given time,” the report says.

City leaders and some residents had high hopes that waves in Long Beach could be an economic stimulus for the area, bringing increased tourism and recreational activities that could put more funds in city coffers for improvements and other projects. A previous city-funded study said the uptick in tourism could draw up to $52 million a year in local spending and $7 million annually in taxes and parking fees.

Army Corps officials contend the impact on the ports would probably outweigh any local economic benefit achieved by removing the breakwater.

Long Beach Mayor Robert Garcia, who has long championed the effort to modify the breakwater, said in a statement that he was disappointed with the results of the study and had been “hopeful that breakwater modification was possible while protecting coastal homes and our port complex.”

He added that the city should be guided, however, by the data included in the reports that showed wave action could also contribute to coastal erosion and flooding in some areas — a longtime concern for residents with oceanfront property.

U.S. Rep. Alan Lowenthal (D-Long Beach) also expressed disappointment.

“I’m aware that the U.S. Navy had some concerns, but I do not believe that they rose to the level that would forgo any reconfiguration options,” he said.

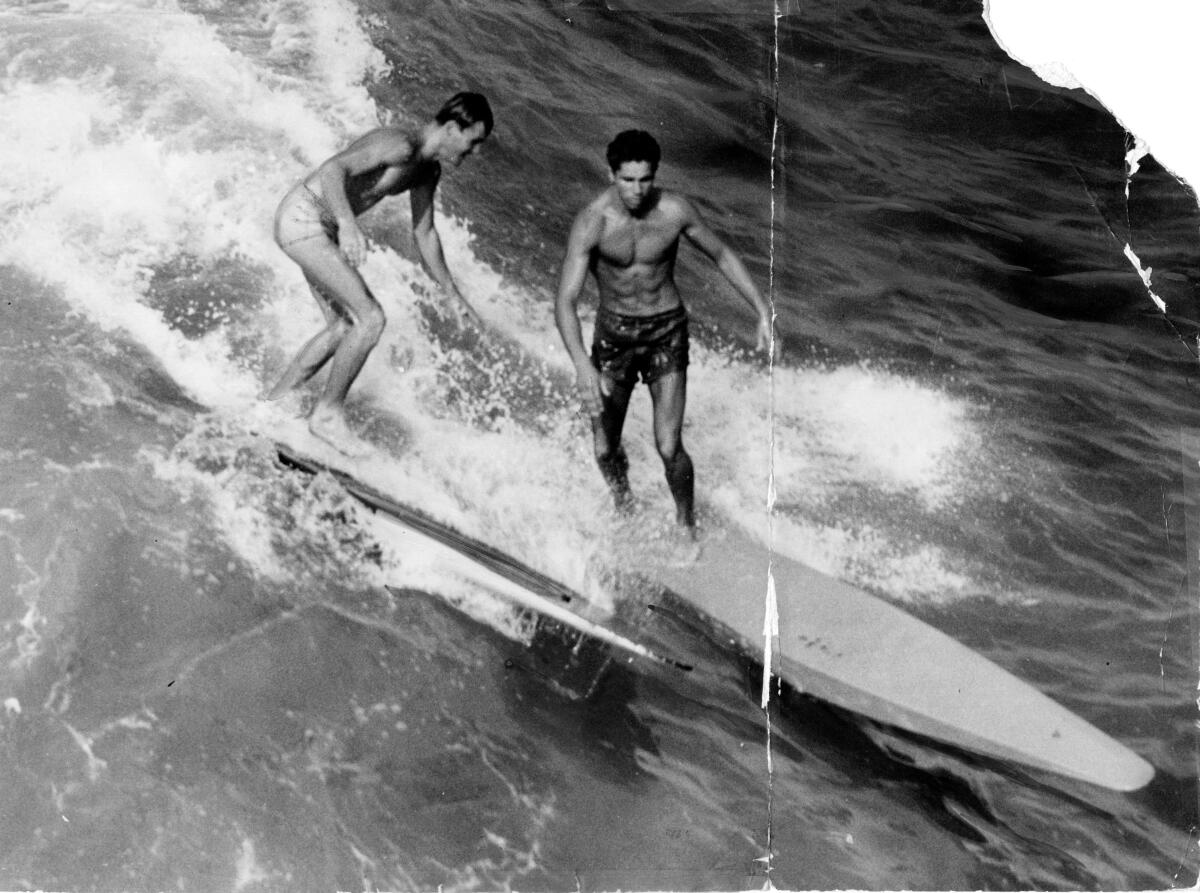

Long Beach was once something of a surfing mecca, known for its roaring swells that attracted surfers from across the region. In 1938, the city hosted what’s been billed as the first surfing contest on the United States mainland, according to local historians.

The event was memorialized in a black-and-white photograph that more than 80 years later continues to circulate as a rallying cry among a community of surfers hoping to bring back the waves. In the photograph, the surfers are lined up shoulder to shoulder along the Long Beach shore with massive wooden surfboards behind them in preparation to launch into the water.

Three years after that contest, work began on the Long Beach breakwater. After it was completed in 1949, the waves vanished and surf-loving crowds migrated to nearby spots like Huntington Beach or Manhattan Beach.

In 1996, the Long Beach chapter of the Surfrider Foundation formed and began publicly calling for removal of the breakwater. The chapter’s chair, Seamus Innes, said the organization was concerned with the Army Corps’ approach to the study and was reviewing its options.

“We’re disappointed that the Navy has put a nix on any sort of activity with the breakwater,” he said. “We’ve been working on this for more than 20 years, and this may put the kibosh on us going forward.”

Advocates for the removal of the breakwater have long contended that the structure traps urban runoff and stormwater from the Los Angeles River, diminishing water quality at local beaches. Tests in the last several years show the water in Long Beach is safe for swimming, except during the rainy winter season.

A beach report card released in June by the nonprofit group Heal the Bay gave two beaches in the city an A grade during the dry summer months. The stretch of beach at the Belmont Pier earned a B, and three other locations earned C grades during the same period.

One beach, though — Long Beach City Beach at Coronado Avenue — received an F grade, earning it a spot on the group’s Beach Bummer list. The report indicated that water quality at that beach was degraded by dry weather runoff, which flows into the ocean through a storm drain on the beach.

Although water quality rankings show it’s safe to dive in, the lack of waves and a muddy tint to the ocean along certain stretches of beach are enough to turn some people away, even during the sweltering summer months, Koller said.

“It can be hot as hell and there’s almost no one in the water,” she said. “I’ve done it because we’ve done paddle-outs for Surfrider, but we all paddle on our knees. I’ve never wanted to get all the way in.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.