Cal State board delays decision on extra math requirement until 2022 amid controversy

Students won’t be required to take a fourth high school math class to be admitted to a Cal State University — for now.

Faced with intense opposition, the Cal State Board of Trustees decided Wednesday to wait two years before voting on whether to require a fourth class in math, science or quantitative reasoning for acceptance into any of the 23 campuses in the nation’s largest public university system. The proposed requirement would affect students entering the university in fall 2027.

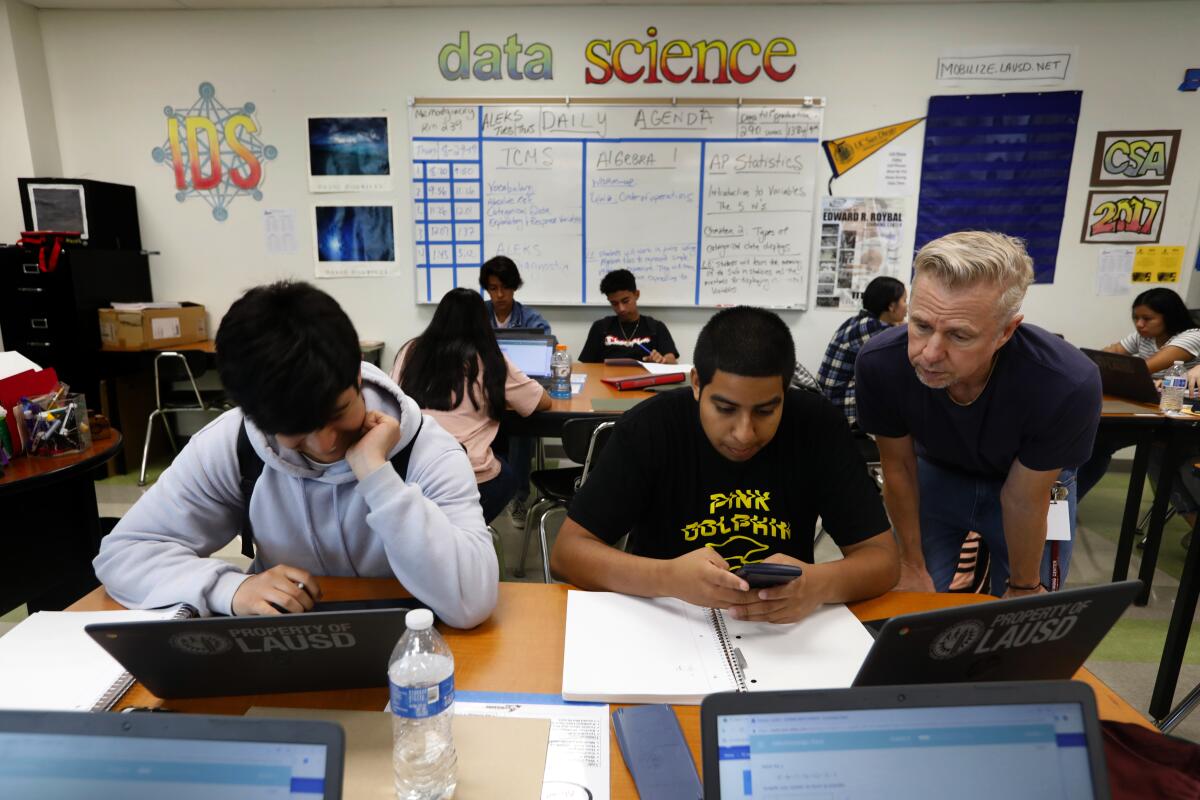

Many community advocate groups and school districts, including Los Angeles Unified, have fought the plan, saying it would hurt black and Latino students and those from low-income families because of disparities in access to math and quantitative reasoning classes and the lack of qualified teachers.

The trustees instead approved, 20-1 with one abstention, a plan by Chancellor Timothy White for a “phased implementation,” which calls for more study on the issue and a final vote in spring 2022. The chancellor will update the board on the study and progress on building teacher and course capacity through January 2022.

A steering committee — to include the head of the board of trustees’ educational policy committee, the state superintendent of education, a Cal State student and a public school district superintendent, among others — will meet twice a year to monitor the “impact and effectiveness of the requirement.”

The chancellor’s office introduced the additional-math proposal in 2017 with the support of the Academic Senate as Cal State educators sought to raise standards and academic preparation for all students, especially in math. Cal State data have shown that students who enter their first year of college having taken an additional quantitative reasoning course are more likely to complete their general education math requirement, return for their second year and graduate.

Outside and inside the board meeting Wednesday, activists and current and former CSU students rallied in support of delaying the decision and called on the university system to offer more resources for the most underserved students.

“We remain unconvinced” that an additional math requirement in high school will lead students to be more successful in college, Michele Siqueiros , the president of Campaign for College Opportunity, told the trustees during public comment. The nonprofit advocacy organization has been one of the leading opponents of the requirement.

“We hope the independent research can quantify what impact this solution would have in terms of access and admissions to the CSU for Latinx, black, Native American, Asian American and low-income Californians,” Siqueiros said. “How will we ensure that any proposal does not have the effect of disproportionately impacting students by race ... ethnicity, income status or ZIP code?”

Cal State Long Beach student Guadalupe Morales told trustees she was speaking to them on behalf of about 250 high school students in Los Angeles who opposed the requirement.

“We want to make sure the study isn’t only being done in affluent communities where the results will show some kind of bias and will only prove their points to be correct,” Morales, 18, told the board. She also asked the board to offer more support for first-generation college students.

The new plan calls for the CSU system to continue partnering with high schools to increase course offerings, and to amp up their own training for math and science teachers. If the requirement is ultimately approved, it could be met by an additional year of math or science, an elective with quantitative content such as statistics or computer science, or some career and technical education courses. An exemption would be allowed for students who cannot meet the requirement because their school doesn’t offer a qualifying course.

Supporters of the additional math course say it is one part of the university system’s plan to eliminate achievement gaps.

“To conceive that disparities in high school preparation are acceptable and inevitable is, frankly, in my mindset, offensive,” Loren Blanchard, executive vice chancellor for academic and student affairs, said during the educational policy committee meeting before the vote Wednesday.

Even after almost two years of discussion about the topic, trustees were split on the issue Wednesday. Student trustee Juan Garcia asked what data would be examined in the study and said student voices should be included in the steering committee — CSU leaders did not yet know who would conduct the study or what it would include.

Trustee Hugo Morales, the executive director and co-founder of Radio Bilingüe, said the additional year of math could negatively affect English-learner students, who in some schools have even less access than other students to these extra math classes. Morales was the only trustee who voted against the proposal Wednesday. Trustee Jeffrey Krinsk abstained.

Some voted yes while expressing caution, worried that even if CSU demanded better preparation and offered help with the goal of pushing school districts to change, they could not ensure that would happen.

“We as the CSU can recommend, we can cajole, we can dangle a carrot or wield a stick, but at the end of the day I don’t know that we have the power to make L.A. Unified School District, the largest school district in California, provide the courses” that students would need, said Lillian Kimbell, the vice chair of the board.

Other trustees, including Long Beach Unified Supt. Chris Steinhauser, reaffirmed their support of the proposal.

Long Beach schools phased in an additional math requirement over four years, and the share of students graduating eligible for Cal State schools has increased during that time, Steinhauser said. Others echoed the sentiment — Peter Taylor said that school districts would rise to the challenge as they did when the Cal State and University of California systems implemented the “A-G” admissions requirements, which many saw as too challenging.

In an impassioned impromptu speech, state Supt. of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond, an ex-officio trustee, admonished board members for suggesting that increasing its standards would necessarily result in better outcomes for black, Latino and low-income students, who suffer because of the effects of systemic racism. There is still a disparity in who is eligible for college in California — about half of the graduating seniors in California met CSU entrance requirements in 2019, and the share was lower for black, Latinx and Native American students.

“There’s no question that decisions about money and race and racism have contributed to the gap that our students experience in this state and this country,” Thurmond said. Increasing standards is a worthy goal but is not enough to ensure the success of historically disenfranchised students, he said.

He has always supported the proposal to add a fourth math class, he said, but cautioned the trustees to focus on implementing the change with adequate support to help K-12 schools prepare students fully.

“Let us not fool ourselves that just by doing this ... we will close the gap,” Thurmond said. “It’s the right thing to do. We set the bar high and then we give our students the resources that we need to get [it] done.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.