Life wasn’t easy on the streets. But, for a time, it was at least predictable.

Terrance Whitten would hang out all day at Farmers Market, the Beverly Center or the Fairfax Library. Then he’d catch the bus to his secret sleeping place: the storage unit where he kept his belongings.

His future brightened when his case manager told him he’d been matched to an apartment in Glassell Park. He filled out the paperwork and previewed the unit.

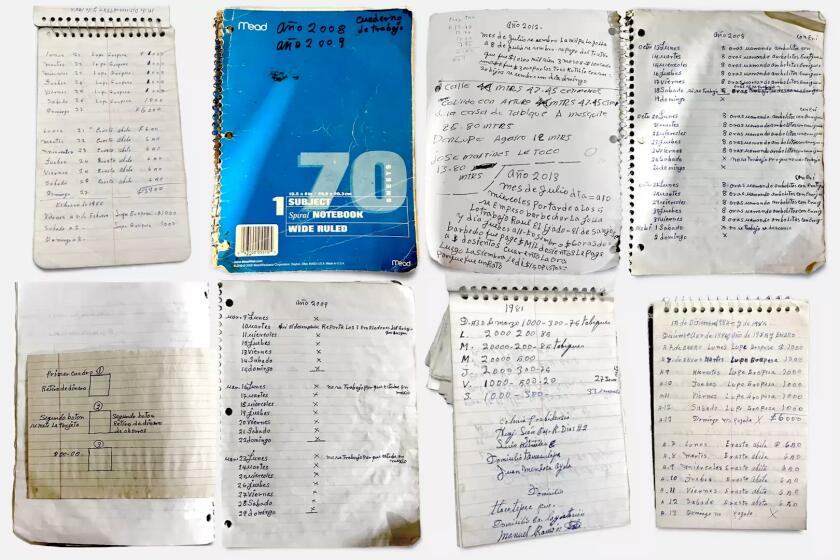

His written record of what came next screams with all-caps pain: “LIBRARIES CLOSE!”; “ALL CITY AGENCIES CLOSE!!!!”; “NOWHERE TO GO.”; “ANGRY DAY.”; “RAIN.”

Those exclamations are mixed with plaintive lowercase: “Gay Center in Hollywood closes.”; “Should have had appointment @HACLA for Section 8 certification!”; “Should have moved into Teague Terrace.”; “speak w/ Denise & Patrick w LAHSA re: hotel room w Project Roomkey.”; “Awful days.”

Whitten’s awful days ended in the last week of June when he moved into his new home, Unit 108 of the Teague Terrace supportive apartments, 127 days after it was reserved for him.

His four-month wait, while the apartment lay vacant, reflects a persistent failing of the countywide system to get homeless people into housing. Even before the novel coronavirus made every step of the process more difficult, apartments routinely remained vacant for 90 days or more, officials with the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority acknowledge.

With an inventory of more than 10,000 units of supportive housing, each of which typically becomes vacant every seven years, the delay means that up to hundreds of units are vacant at any time waiting to be occupied by someone living on the street.

LAHSA, the homeless authority, made fixing that problem a priority late last year and set up a task force to find and eliminate the bottlenecks.

The goal is to leave no unit vacant more than 20 days, said Sarah Dusseault, chairwoman of LAHSA’s governing board.

The task force, called the Housing Central Command, was just making progress when the coronavirus brought it to a halt and put new obstacles in the way. Mandatory in-person interviews at the authority were suspended. Paperwork now must be routed to workers stuck at home.

But that does not justify Whitten’s protracted wait, Dusseualt said.

“Fundamentally, this is not acceptable,” she said. “We have to do better. What we’ve seen in context of COVID is we have to do more to clear regulatory hurdles.”

I proceeded to have a nervous breakdown and tried to kill myself.

— Terrance Whitten

Whitten, who is slight of build and walks with a cane, is articulate, organized, proficient in the bus system and quick to respond to his case manager’s requests. In short, he couldn’t have been an easier client to serve.

An artist who makes vibrant color pencil drawings on symbolic themes, the Detroit native arrived in Los Angeles in 1999 by way of New York and Seattle hoping to get traction on another artistic pursuit, his un-optioned screenplay for Ayn Rand’s novel “The Fountainhead.”

To get by, he worked at Borders, then, after becoming disabled from a slipped disc, taught English as a Second Language for a Korean school. He lived in low-income housing at the Rosslyn Hotel downtown.

His slide began in 2011 when the U.S. government required all teachers who taught English to foreign students to have Teacher of Foreign Language certificates. Without one, he was laid off and unable to find a new job.

“People can’t hire me because of insurance,” he said. “They just don’t want an injured worker.”

When his unemployment ran out in June of 2014, he surrendered his lease at the Rosslyn and moved his belongings into storage.

His next situation ended when a friend who had put him up ran out of money and jumped off the Colorado Street Bridge in Pasadena.

“I proceeded to have a nervous breakdown and tried to kill myself,” Whitten said. That led to the first of two commitments, the second precipitated by his eviction from his storage unit.

“The manager at Farmers Market Self Storage started finding reasons to evict homeless people and people they didn’t want on the premises anymore,” he said. “I was one of them.”

He moved his things to storage in Venice and found that local gangs made camping on the nearby streets impossible.

That’s when he improvised a lifestyle.

“Once I had everything set up I realized I had space to lay down in,” he said. “I said, ‘Do it.’ It’s so profoundly quiet at night in those spaces. You can hear your blood going through your veins.”

For about a year he used Metro to spend pleasant days at USC’s Doheny Library until a security guard handed him a letter from the chief librarian asking him not to return.

A spokesman for USC said he could not comment on an individual but provided a statement saying the university will issue a stay-away order “if a person has repeated complaints or instances of harassment of students and staff.”

“They thought I was a vagrant,” Whitten said.

Last September, he saw an opening to a better life and went for it. He approached an outreach worker at the Fairfax Library. His age, 67, coupled with his disability and suicidal episodes, gave him high priority for housing. The outreach worker, Cindy Ramirez, called him on Feb. 18 with the good news that he was matched to a vacant apartment.

On Feb. 25, Whitten took the bus to the downtown office of the People Concern homeless services organization to fill out paperwork certifying his disability and verifying his homelessness. The forms would require signatures of the medical and homeless services providers who could vouch for his status, a tedious job for his caseworker.

On March 5, he previewed the one-bedroom unit and was delighted with its good feng shui. He filled out his rental application and returned a week later to meet his caseworker from Housing Works, the service provider for Teague Terrace, and fill out a lengthy application to the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles for a Section 8 rental subsidy. But the application couldn’t be completed without all the signatures on the homeless certification.

The next step would have been an in-person interview at the Housing Authority. It never happened because the coronavirus forced the agency to send its workers home.

With all his haunts closing, Whitten began an eight-week stay in and around Pan Pacific Park, where he sat under a tree for much of the day until it was time to take the bus back to his storage unit in Venice. The conversion of the recreation center there into a pop-up shelter — which he declined to use — shut him out temporarily from one of his amenities, the shower. His complaints were finally heard, and he was allowed to shower on March 31.

Then it rained. April 9 and 10 were low points: “RAIN, stood all day. Awful days.”

By then Whitten was on the waiting list to be moved into one of the hotels leased by the county for vulnerable homeless people like him. But as leasing for Project Roomkey lagged, he waited for weeks.

Ramirez, the People Concern outreach worker, joined him at Teague Terrace on April 16 to fill out a new form certifying that he alone would live in the apartment and to fill in some missing details on his application to the Housing Authority.

Then another three weeks passed waiting for the Housing Authority to conduct a mandatory inspection of the unit and review the application. When the application came back with corrections, Whitten went to Teague Terrace for the fourth time on May 8 to re-submit it.

The wait was typical of the bureaucratic checkpoints that slow the housing process, leaving hundreds of units empty for weeks or months. Multiple outreach workers and case managers from different agencies fill out documents with signatures from the client, case managers and others who knew the client. IDs and Social Security cards have to be gathered, background checks to be done.

The Housing Central Command was created to apply disaster management procedures to the problem. It assembled officials from nearly a dozen agencies that manage housing supply or work with people who need the housing. The group met daily to identify and open up bottlenecks.

It achieved some quick fixes, such as persuading all 18 housing authorities in L.A. County to accept digitized identification so that clients don’t have to produce paper ID at every step.

Some bottlenecks are out of local control. LAHSA is seeking permission from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to let clients move in first and track down their Social Security cards later. Meanwhile, HUD has allowed case managers to present copies of Social Security cards, but there is still no solution for those who don’t have cards to copy.

“In this moment where getting to a Social Security office is incredibly difficult, we’ve got to think of ways to place people quickly without hurdles,” said Dusseault, LAHSA’s chairwoman.

The effort came to a standstill when LAHSA shifted its focus to getting the most vulnerable population into shelters during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It has recently regrouped, holding Friday digital conferences with housing officials. They have been working on streamlining forms and background checks, Housing Central Command Director Amy Perkins said. But to reduce vacancies from months to days, she said, a deeper change is needed. The process needs to be turned around so that all the documents needed for a complete application are in hand before a client can be matched to an apartment.

Whitten’s case shows what happens when they aren’t.

On May 8, Whitten went to Teague Terrace for the fourth time to fill in missing pieces in his application to the Housing Authority.

With his move-in date still not in sight, he got a call from Ramirez on May 11 with some good news. She had arranged temporary housing through Project Roomkey in one of the trailers the city placed in the parking lot of Friendship Hall in Los Feliz. The next day he took the bus there.

“BY THE RIVER!” he wrote.

Ramirez dropped by his trailer two times, on May 26 and June 4, to update the certification forms that had expired, she said.

On June 5, Whitten received bad news from Ramirez: there was a delay at the Housing Authority and she had accepted a new job with L.A. County’s Housing for Health program.

On June 17, he met with Ramirez for the last time to fill in a missing signature to his income form.

“Cindy Ramirez gone. Can’t communicate w/her. BUMMED,” he wrote two days later.

But she didn’t just drop him. On June 23, Ramirez called to say he had cleared all the hurdles and could move in.

He signed the lease six years to the day after he became homeless, fulfilling for him a sense of a loop being closed.

In his first week in his apartment, he set up his drafting table to resume his artwork while he waits for the break he hopes will get his screenplay optioned.

He’s happy but not entirely at peace at times, when his Catholic guilt kicks in.

“There are painful stories that are out there,” he said, “People out there in far worse shape to use these resources on than me. I had the wits to be able to survive to some degree.”

But then he backtracks. “You got this. Enjoy it. Get back to work.

“I don’t know if this sounds heartless, but I had to come to the realization that all that pain out there is not my responsibility. Whose responsibility is it?”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.