California approves ethnic studies curriculum for K-12 schools after years of debate

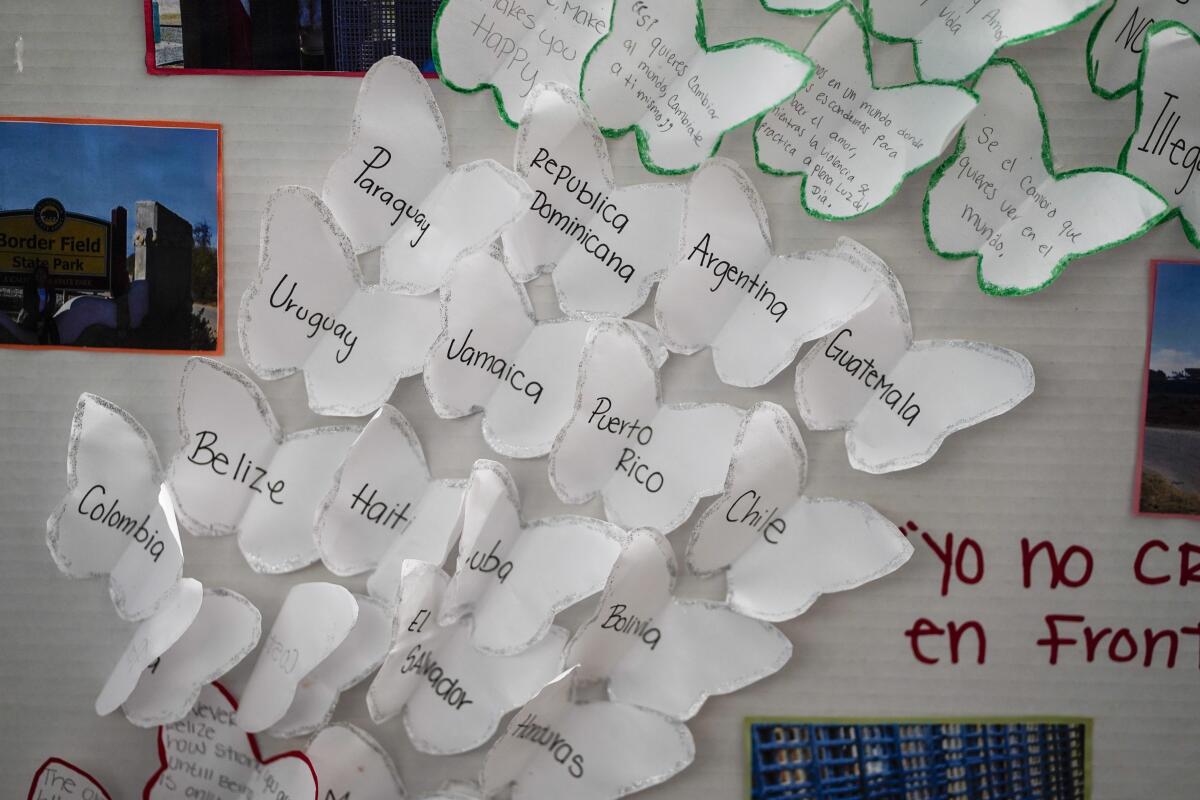

Ending years-long and often divisive debate over ethnic studies coursework in California’s K-12 schools, the State Board of Education on Thursday unanimously approved a model curriculum to guide how the histories, struggles and contributions of Asian, Black, Latino and Native Americans — and the racism and marginalization they have experienced in the United States — will be taught to millions of students.

The new curriculum embraces an approach to ethnic studies that focuses on the four core groups but evolved to accommodate a breadth of experiences, including lessons on the Jewish, Armenian and Sikh communities in the U.S.

Although criticism still emerged Thursday, the curriculum approval culminates two years of difficult discussions, protests and rewrites over which groups should be included and how their stories should be presented. Drafts were alternately pilloried for being left-wing propaganda or capitulating to right-wing agendas, and defended as providing an essential means for students of color to see themselves reflected in public school curriculum. It comes at a time when educators are seeking concrete lessons and strategies to address racism.

“The passion that we hear about this topic illustrates why ethnic studies is so important,” board president Linda Darling-Hammond said after nearly eight hours of presentations and discussion. “Much of it is a quest by each person or each group for a sense of belonging and acknowledgement.”

“Ethnic studies demands that we understand the forces that stand in the way of our shared humanity so that we can address them,” she said. “We need the more complete study of our history that ethnic studies provides and the attention to inequality that it stimulates.”

For now, the model curriculum serves as a guide for school districts that want the option to offer ethnic studies. But its lessons stand to become a flashpoint for debate again in the months ahead, as a bill to make a high school ethnic studies course a graduation requirement — believed to be the most far-reaching law of its kind nationally — makes its way through the Legislature.

The final vote came four years, four drafts and 100,000 public comments after state law mandated that educators create a model studies ethnic studies curriculum.

“In a state with the most diverse student body of anywhere in the nation, our students must see themselves reflected in their school, their curriculum, and the knowledge they learn,” Luis Alejo, author of that legislation when he was in the Assembly, said at the meeting Thursday. “This first-in-the-nation model curriculum will show other states what is possible.”

Supporters said the anti-racist teachings and the historic perspectives of marginalized groups in the curriculum are of critical importance at this moment in the U.S. as it reckons with issues including the Black Lives Matter movement and police abuse, violent attacks on Asian Americans and the rise of hate crimes against them, and attempts to disenfranchise voters of color.

“What we … have to do is take steps to start preventing these horrific acts against people of color,” said civil rights icon Dolores Huerta, whose social justice foundation works with several school districts. “It is not enough to say, I am not a racist. What we have to do in today’s world is we have to be anti-racist…. There is no place that has the greatest responsibility than our educational system.”

“We are proud of what we have to present to you,” State Supt. of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond told the board Thursday. “And we acknowledge that when you do something of this magnitude it will not make everyone happy, but what we strive for is balance.”

The first draft of the curriculum was besieged by controversy and criticism, in large part from Jewish groups and legislators who objected to its treatment of Jews, exclusion of anti-Semitism as a form of hate, and mention of the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions protest movement against Israel. Others, too, argued it was heavy on academic jargon, filled with left-leaning ideology and a controversial glossary that included definitions of terms like “hxrstory” and “cisheteropatriarchy.”

Other ethnic groups, including Armenian Americans, Sikh Americans and Arab Americans, also variously protested their exclusion or the terms under which they were included.

Another focal point of debate was “critical race theory,” a lens to examine how race and racism are embedded in institutional and systemic inequities. Frequently attacked by former President Trump and misinterpreted as creating divisions among groups, critical race theory is seen by ethnic studies practitioners as inseparable from the field, and the board recommended adding a definition to clear up misconceptions about it.

The curriculum now includes a discussion of anti-Semitism in a sample lesson about Jewish Middle Eastern Americans and an additional sample lesson about Jewish Americans , both submitted by Jewish educators, in a section on “inter-ethnic bridge building.” Armenian and Sikh Americans are included in that section as well. So are Arab Americans — a sticking point, as Asian American Studies faculty have long considered Arab Americans to fall under the umbrella of their discipline.

In a sign of how much has changed, some of the loudest objectors to the initial curriculum, including the California Legislative Jewish Caucus and the Jewish Community Relations Council, have withdrawn their objections.

“We need ethnic studies now,” Tyler Gregory, executive director of the Jewish Community Relations Council said Thursday. “Ethnic studies gives marginalized communities the agency to define and share their own stories, cultures, and histories. As Jewish Americans, we relate to this urgent need.”

“Our crucial inclusion presents our own chance to impart the richness of our people, so that future generations hear the dog whistles of anti-Semitism that too often fall on deaf ears,” Gregory said.

But all of the ethnic studies teachers and experts initially appointed by the State Board of Education to draft the curriculum have asked to withdraw their names from it.

In a February letter to the top state educators and policymakers, members of the original advisory committee wrote: “Ethnic Studies guiding principles, knowledge, frameworks, pedagogies, and community histories have been compromised due to political and media pressure. Our association with the final document is conflicting because it does not reflect the Ethnic Studies curriculum that we believe California students deserve and need.”

Theresa Montaño, a professor of Chicana/Chicano studies at Cal State Northridge and a member of the advisory committee, said in an interview that, due to the heavy influence of public comments, the curriculum had moved further and further away from ethnic studies, removing core concepts and terms, and much closer to a multicultural social studies or history course.

“While we would argue that ethnic studies is for all students and we do honor multiple perspectives in our classrooms, the content should be on the racialized communities of color,” Montaño said.

“Ethnic Studies is the opportunity to give one course to the 80% of California students who have begged for inclusion of their histories and their stories in the California curriculum,” she said. “One course in 12 years. One. And you couldn’t even do that…. That’s what’s the most disappointing.”

Splits over the curriculum — including within the Jewish community — were again apparent during public comment on Thursday. Some Jews criticized it as insufficiently addressing anti-Semitism and the place of Middle Eastern Jews. Others said the model curriculum process had been “co-opted” by anti-Palestinian, pro-Israel groups.

Other supporters of traditional ethnic studies said the latest version had been stripped of its “anti-racist, anti-colonial and liberatory tenets” with the removal in places of terms like “revolution” and “capitalism,” as well as of substantive discussion of Palestinians.

Montaño said that ultimately what matters is what happens in the classroom, where teachers, students and parents will carry out the actual work of implementing ethnic studies.

Secretary of State Shirley Weber, a longtime professor of Africana studies and a former member of the body that reviewed drafts of the model curriculum, said Thursday that the curriculum will provide needed parameters for educators around the discipline.

“Criticism will continue, I can guarantee you that. The robust conversation will continue…. What is in the discipline, what is not in the discipline, what’s appropriate material to use,” she said.

“Curriculum is not a static thing … but you have to take the first step. And we cannot let the perfect be the enemy of the good. We will not find the perfect curriculum, but we have found a good curriculum, one that is strong.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.