Ignore, explain or fight back? How Asian Americans deal with racism

As Syl Tang boarded an elevator in New York City this month, a woman pulled up the corner of her eye in a familiar gesture mocking Asians.

The woman then launched into a coronavirus tirade — she had stayed at home for a year and done everything right, yet “a foreigner” gave her the virus.

Tang’s anger rose as she found herself in that well-trodden crossroad faced by anyone targeted because of race, gender, sexual orientation or religion: Stay quiet, or say or do something and possibly risk an escalation?

For many Asian Americans, from immigrants to fifth generation, incidents like the one Tang endured have been an all too normal part of their lives — usually not rising to physical attacks but feeling at times like a window into a deeper well of hate.

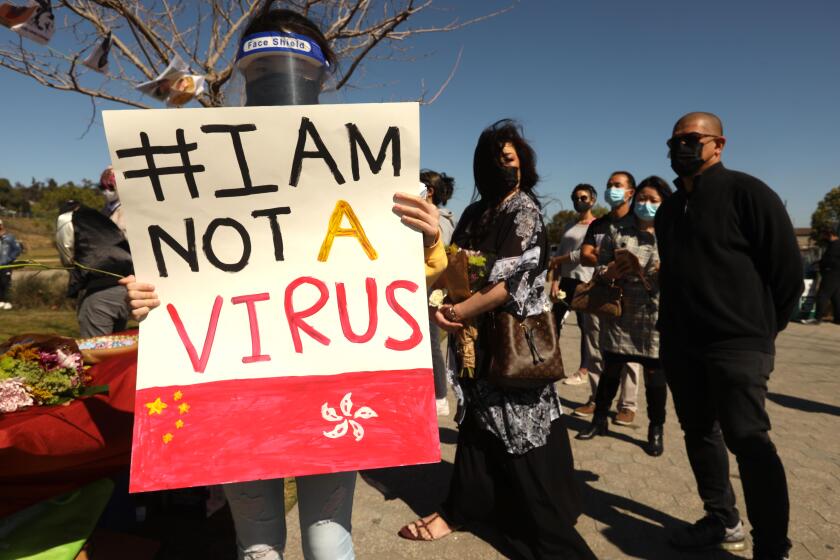

Now, a recent spate of attacks against Asians, punctuated by the mass shooting in Atlanta last week that killed eight people, including six Asian women, have put a spotlight on more mundane incidents of bigotry.

The verbal harassment happens in elevators, restaurant bathrooms, taxis and public sidewalks, thrusting victims into a situation for which there is no playbook.

Do you make a joke of it, laugh it off and try to make the moment end? Silently walk away? Explain why the words were hurtful? Tell the person off?

What if, as in videos captured across the country, the encounter turns violent?

Even before the Atlanta-area spa attacks that killed eight people, including six women of Asian descent, volunteer groups have sprung up to defend their Asian American communities in California.

Inside the elevator, others chimed in and said that COVID had been “brought here.” Tang decided to say something.

“I would like you to know that I’m vaccinated,” said Tang, who wanted the woman to hear that she spoke English fluently and without an accent.

“I wasn’t going to get into a fight in an elevator with this woman, but it was very clear to me that in her eyes, I was a foreigner,” Tang, 48, who is Chinese American, said later.

Tang, the author of a world affairs book, has endured racist incidents on a weekly basis, even before the pandemic.

Once, a group of tourists pulled her out of a cab while telling her to “go back to squatting on the ground in my pajamas in China.” Another time, a woman shoved her off a subway train onto the platform and called her a derogatory term for Chinese people. Countless times as she walks down the street, men have shouted, “Me love you long time,” “Ching chong ni hao” or “Konichiwa” and then, when ignored, followed up with expletives.

A month ago, a woman spit on her in a restaurant bathroom, saying she didn’t “want to get the coronavirus.”

“I think you take it incident by incident. You try to assess whether it’s worth it to fight back, whether it’s worth it to say something,” Tang said. “I have yelled back at racist slurs on the street. When people say things to me, especially if they assume I don’t speak English, I have some choice words for them.”

But to respond every time would feel akin to living in a constant state of combat.

“If you’ve been going through this for decades, you go through periods where you’re really angry, periods where you’re resigned, then you’re really angry again, then you’re resigned,” Tang said. “You sort of go back and forth. … Mentally, you may always want to fight back and you may always want to speak up, but you get tired.”

Before Los Angeles musician John Bach goes on tour with a new band and crew, he sits them down to “have the talk” about racist comments and physical attacks he will likely get — especially when it’s a tour through the Deep South or the Midwest.

The 36-year-old, who has been a professional drummer for 17 years and is of Korean descent, has been told, “I’ve never seen an Oriental play drums before” and “Didn’t know a Chinaman can do much else besides math. Let me buy you a beer.”

He ignores the racial stereotypes embedded in the comments and maintains a friendly demeanor.

“I usually deflect and ignore statements. I don’t respond in anger, ever, unless I have to defend myself, which is pretty rare, although it does happen,” said Bach, who was born in South Korea and moved to California when he was six. “I approach the situation as I would with any other fan. Just keep the mood light, take whatever it is that they say as a compliment.”

Some people, including former President Trump, have blamed Asian Americans for the coronavirus because it first emerged in China.

About 68% of the anti-Asian attacks documented during the pandemic were verbal harassment, 21% were shunning and 11% were physical assaults.

Last March, Manjusha Kulkarni was in a hair salon when she overheard two white women saying that Asians spread disease because of the food they eat, citing bats. She weighed whether to say something.

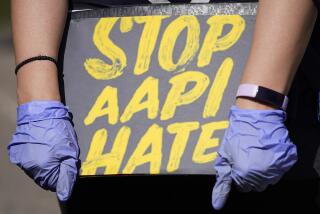

“There’s a social etiquette of not challenging things,” said Kulkarni, the executive director of the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council and the co-founder of Stop AAPI Hate. “We’re socialized not to say things to people. It’s rude. It’s potentially disrespectful.”

So Kulkarni said, shaking as she did: “I apologize for interrupting your conversation. I have to tell you what you’re saying is inaccurate.”

“I thought that was the mildest thing I could say and still, their answer to me was, ‘You misunderstood what we were saying,’” Kulkarni recalled.

Along with the trauma suffered in the moment, there are the lingering questions: Could I have said something differently? What if I had said this instead?

“I would feel worse not doing something than doing something, but that’s in environments that were still safe,” Kulkarni said. “If you asked me, ‘Would I do it alone around a big man?’ No, I would not.”

When Jackie Louie was a student at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, a few men in a truck drove by and shouted racial slurs at her and her friends, who were also Asian American.

“We didn’t say anything back,” she recalled. “We were silent. We were shocked.”

After some students made fun of her parents for speaking Chinese, her father said he had ignored them because it was better not to cause trouble.

Now she has rehearsed comebacks in her head after hearing about recent racist attacks against Asian Americans.

“I feel like the right thing to do is speak up and defend either myself or whoever is being victimized,” the 30-year-old Torrance resident said. “However, I really don’t know how it would be until I’m in the moment.”

Joy Kim, who grew up in Orange County, was recently in a New York park when a man asked her age. She has often been told by strangers that she looks young, usually followed by, “It must be your Asian genes.”

The man seemed friendly at first, so she responded that she was in her 20s. The man told her she looked like she was 2.

“You can never tell with you Chinese people,” he said.

“I’m actually not Chinese,” said Kim, who is Korean, reflexively correcting him.

“You’re lying. You’re Chinese. You have COVID,” he told her. “Don’t ever take your mask off because you’ll give us all COVID.”

As Kim walked away, the man screamed after her, calling her a “b—” and threatening to cut off all her hair.

“I almost want to just hide and not say anything or just like not be part of the situation anymore,” said Kim, who ignores and avoids eye contact with strangers on the street who have greeted her with “Ni hao” — “How are you?” in Mandarin. “I guess I sort of was taught that reacting with anger or anything will make the situation worse.”

What weighed on the 25-year-old the rest of the day was not just the interaction with the stranger but the remarks from friends and acquaintances over the years that she had previously convinced herself were harmless.

“If someone said something racist against Asians in the past, I think I would just laugh it off, I guess, move on, and just like hold your anger for later,” she said. “Now I feel like things have changed.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.