The Grammys’ hip-hop game changers Kendrick Lamar and Jay-Z: An East Coast-West Coast contest

BOTH MEN HAVE SOLD millions of albums. Both have headlined the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival. And both made former President Barack Obama’s list of his favorite songs from 2017 — an especially meaningful achievement, perhaps, for two African American artists eager to share their political views (not to mention their scorn for the guy who now holds Obama’s old job).

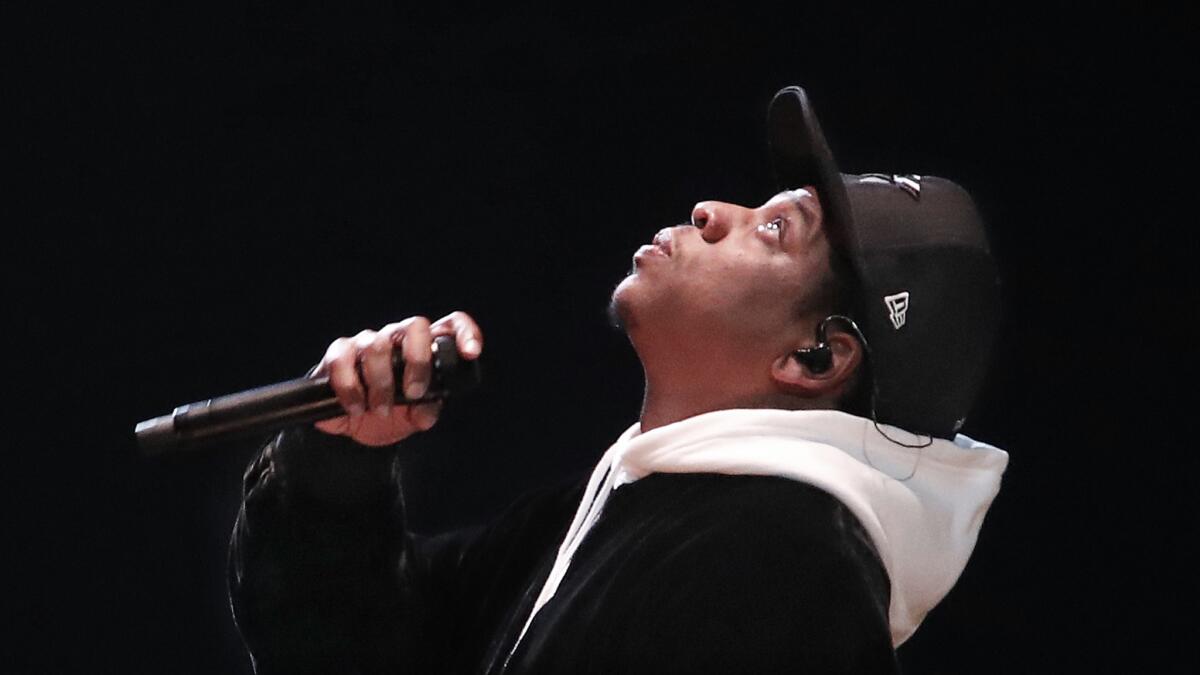

So in a year when hip-hop might finally rule the Grammy Awards, it makes sense that Jay-Z and Kendrick Lamar would be the rap kings closest to victory come Sunday night.

With eight nominations, Jay-Z, the assured veteran, leads the field of contenders for music’s most prestigious prize, followed closely by Lamar, the upstart phenom, who has seven.

All of Lamar’s nods put him in competition with Jay-Z, in categories including album of the year, where his anthemic “Damn” is up against Jay-Z’s more intimate “4:44.” (They’ll also vie for record of the year, rap album, rap song, rap performance, rap/sung performance and music video.)

And Jay-Z’s eighth nomination? It’s for song of the year, for his album’s confessional title track, which marks only the second time in Grammys history — following Eminem in 2011 — that an MC has been nominated for the three biggest awards on one night.

If the overlap between Lamar and Jay-Z suggests that the two are cut from the same cloth, though, the work they’re being recognized for presents a different picture.

A hip-hop game changer: How Grammy-nominated Tyler, the Creator became Tyler, the entrepreneur

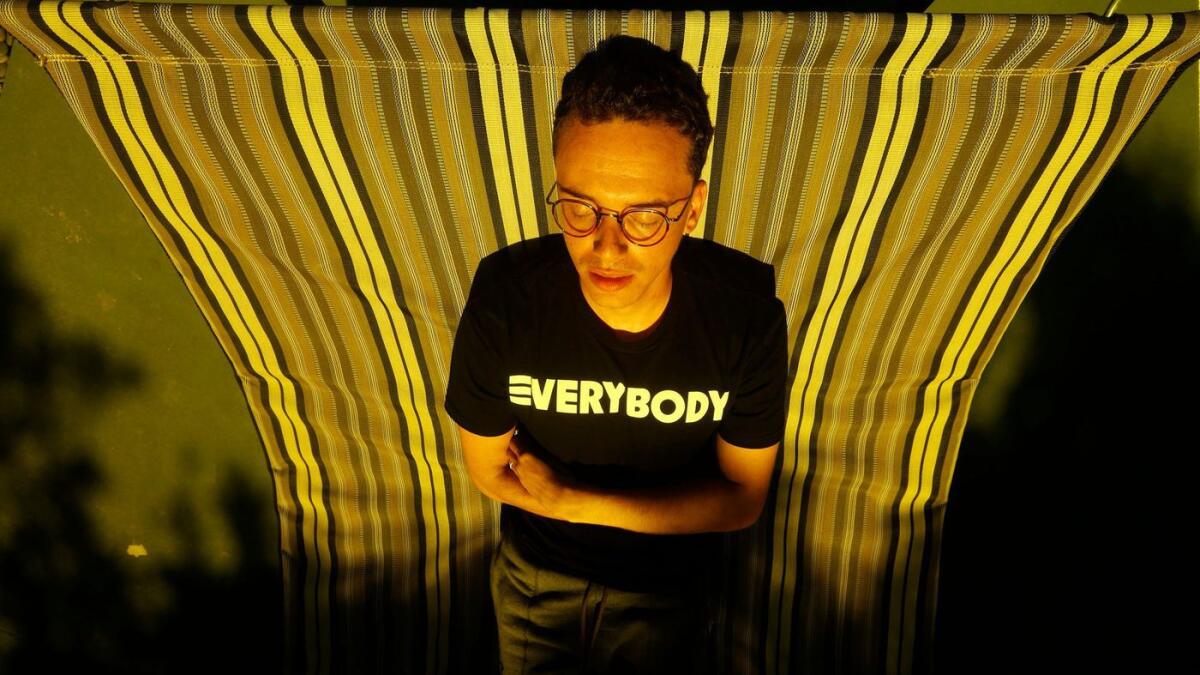

“JELLYFISH ARE EVIL,” Tyler, the Creator, declares with absolute certainty.

We’re at Hollywood’s Chalice Recording Studios, where Tyler fidgets with a piece of studio equipment as he talks, his fingernails shiny under a coat of glittery silver polish.

“They’re smarter than us, almost,” he continues. “When they learn how to drive and use Google, we’re [screwed]. A lot of them don’t die, they split into two and then they’ve got homies.”

The Grammy-nominated rapper — he’s up for rap album with last year’s introspective “Flower Boy” — isn’t randomly discussing his strong disdain (OK, hatred) for the squishy, poisonous sea creature. The tentacled animal was part of the inspiration for “The Jellies,” the Adult Swim animated sitcom he co-created with Lionel Boyce. But that’s just one of many projects that keeps the 26-year-old busy.

Consider the particularly action-packed two weeks in October when Tyler premiered “The Jellies,” hosted his sixth annual Camp Flog Gnaw music festival and carnival, launched a fall concert tour in promotion of “Flower Boy” and debuted the Los Angeles flagship store for his apparel line Golf Wang to the kind of fervor normally reserved for a Supreme launch. This month, he released a new design of Golf le Fleur sneakers and is starting another “Flower Boy” tour. With plans to expand into furniture and film in the near future, Tyler is just getting started.

After losing steam, the Stereotypes almost hung it up — now they are up for Grammy producer of the year

A moment of panic came over Ray Romulus during the 2016 Grammy Awards when his phone buzzed with a notification that his checking account had gone red.

“Taylor Swift is to my left. Selena Gomez is [nearby]. I can see Bruno [Mars]. I’m sitting eight rows from the stage and I turned to my wife to tell her,” Romulus remembered while looking at a screen grab of himself from the telecast — the wide smile he typically wears gone, his brow wet with sweat.

It was music’s most celebrated night, and Romulus — one-quarter of the multiplatinum songwriting and producing collective the Stereotypes — was worried about how he’d take care of his family.

“[My wife] could see the defeat in my face. But she told me, ‘Don’t worry, in a couple of years you’ll be back and it will be for producer of the year.’”

Her prediction turned out to be spot on.

After more than a decade of crafting hip-hop, R&B and pop hits for myriad pop stars, the Stereotypes are having their biggest moment yet with a handful of Grammy nominations, including producer of the year (nonclassical) for their work with Mars, Fifth Harmony, Sevyn Streeter, Lil Yachty, Iggy Azalea and Kyle.

On a recent rainy afternoon in Santa Monica, Romulus, Ray Charles McCullough II and the group’s co-founders, Jonathan Yip and Jeremy Reeves, are tracing the ups and downs that have marked their time together.

Young rappers are getting honest about doing battle with depression, drug addiction and suicide

BACK IN DECEMBER, in front of a sold-out audience at the Forum awaiting Grammy front-runner Jay-Z, opening act and rapper Vic Mensa vaulted onstage. Dressed in punky red leather, he was boisterous and triumphant, the show a crowning achievement in his career.

But underneath the bravado were lacerating lyrics about depression and drug addiction.

“In the cyclone of my own addiction,” he rapped on his song “Wings.”

“The voices in my head keep talking… / ‘You’ll never be good enough…you never was / …You hurt everyone around you, you’re impossible to love / …I wish you were never born, we would all be better for it / …You’re still a drug addict, you’re nothing without your medicine / Go and run to your sedative, you can’t run forever, Vic.’”

Hip-hop artists Jay-Z, Kendrick Lamar and Logic will likely dominate the top Grammy categories, doing so in a year the genre went deep into issues of mental health, drug addiction and suicide — topics that have long been present below the surface. Some acts, such as Logic (with Khalid and Alessia Cara), will tackle those issues head on at the Grammy ceremony, where they’ll perform the smash “1-800-273-8255” (which directs fans to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline) with a group of suicide loss survivors and people who have recovered from suicide attempts.

After the song’s music video went viral, calls to the lifeline went up between 30% and 50%, said John Draper, the suicide prevention line’s director. “That’s thousands of callers who otherwise wouldn’t have called,” he said. “Messages like Logic’s, where he says, ‘I’m thinking about suicide, but I want to get help’ and he got it, are a very positive model.”

But some, like the promising rapper Lil Peep, didn’t hear it in time. Peep died at age 21 in November of a suspected overdose, after a short career in which he wrote openly about his suicidal impulses and drug addiction. Many of his young peers in the “Soundcloud Rap” generation lyrically fetishize the abuse of prescription drugs like Xanax or “lean” (a codeine-laced cough syrup drink), with some such as new artist nominee Lil Uzi Vert alluding to suicide, violence or overdosing as a likely fate for almost everyone they know.

Now that the genre is finally more open about its dark mental storms, how should artists write and work in honest ways, while also helping those who are truly suffering?

Young black men experience a lot of trauma. They’ve lost people, seen violence, been humiliated by society.

— Vic Mensa

How Compton’s Rosecrans Avenue became L.A. hip-hop’s Main Street

LIKE SUNSET BOULEVARD and rock or Beale Street and the blues, Compton’s Rosecrans Avenue — described in song by producer-rapper DJ Quik as “a long-ass avenue that goes from the beach to the streets” — conjures a musical essence beyond the pavement itself.

If Compton is the heart of L.A. hip-hop, Rosecrans is its pulse.

Rosecrans has played a role as an incubator for essential Los Angeles rappers such as Kendrick Lamar, Dr. Dre, YG, the Game, DJ Quik, Problem and dozens more. Since N.W.A’s 1988 album “Straight Outta Compton,” artists have long used the 27-mile-long avenue as a backdrop.

Yet whereas songs about Sunset Boulevard have tended to romanticize the sun-drenched Southern California ideal, those set 15 miles south on Rosecrans have been riddled with violence, a truth that frustrates attempts to reframe Compton’s image.

You won’t hear lyrics about the city’s birth as the flood-prone midpoint between downtown Los Angeles and the L.A. harbor, or about how in the 1940s a huge migration of African Americans transformed South L.A.

“Who blew up that McDonald’s on Rosecrans and Central, dude?” wonders King Tee in his 1987 track with Mixmaster Spade and the Compton Posse, “Ya Better Bring a Gun,” which is the first known rap song to utter the avenue by name. The McDonald’s is still there — right across from Tam’s Burgers at Rosecrans and Central avenues.

“This is where I seen my second murder, actually,” Lamar told Rolling Stone at Tam’s Burgers in 2015. “Eight years old, walking home from McNair Elementary. Dude was in the drive-thru ordering his food, and homey ran up, boom boom — smoked him.”

ALSO: Explore Rosecrans Avenue and listen to its music, a tour of L.A. rap’s Main Street

Compton’s Most Vaunted: Who would deserve a spot on a Rosecrans Walk of Fame?

What are the best songs that reference Rosecrans Avenue?

How hip-hop storyteller Kendrick Lamar describes hometown Compton

Explore and listen to the music of Rosecrans Avenue, rap’s Main Street

SINCE THE RISE OF RAP in the 1980s, Rosecrans Avenue in South Los Angeles and Compton has served as the music’s West Coast spiritual home. Extending 27 miles from Fullerton to its end at Pacific Coast Highway in Manhattan Beach, the street, named after a Union soldier, has been an actor in songs by Kendrick Lamar, YG, Problem, DJ Quik, 2Pac and dozens of others. Take a tour of Rosecrans Avenue, and check out our Spotify playlist.

ALSO: How Compton’s Rosecrans Avenue became L.A. hip-hop’s Main Street

Compton’s Most Vaunted: Who would deserve a spot on a Rosecrans Walk of Fame?

How hip-hop storyteller Kendrick Lamar describes hometown Compton

Hip-hop’s television takeover

THE CEREMONY FOR the 60th Grammy Awards is still two weeks away, but already music’s biggest TV night has made history.

For the first time, hip-hop artists dominate the majority of nominees chosen in the academy’s top categories, including record, album and song of the year.

But that sound you’re hearing isn’t champagne corks popping in celebration. It’s exasperated sighs that the Recording Academy only just discovered what the rest of the entertainment industry noticed back in the flip-phone era: Hip-hop, once an outlier, is now the status quo.

From Broadway’s “Hamilton” to Hollywood’s “Straight Outta Compton” to television’s “Atlanta,” hip-hop’s broad influence on American pop culture has defied countless predictions that a nervous white mainstream would never fully embrace a trend born out of the urban black experience.

Consider hip-hop’s television takeover. Today, rappers are not only backing films about the black experience, but they are creating, producing and starring in top-rated cable and network series and breaking out of music categories at film and television award shows.

Hip-hop is the soundtrack of at least one, probably two generations now. … It’s part of everything … and everyone under the age of 40.

— Common

How hip-hop fashion went from the streets to high fashion

FOR HIS FALL 2017 women’s fashion show, designer Marc Jacobs sent models down a stripped-down runway at New York’s Park Avenue Armory last February wearing tracksuits topped with thick gold chains, retro-style coats and eccentric headwear, a hat tip to hip-hop’s early days in the late 1970s and early ’80s.

Jacobs’ collection was inspired, he said, by two things: the 2016 Netflix documentary “Hip-Hop Evolution,” which chronicles the music genre’s rise from the ’70s through the 1990s, as well as memories from his own New York childhood.

“This collection is my representation of the well-studied dressing up of casual sportswear,” the designer explained in a statement. “It is an acknowledgment and gesture of my respect for the polish and consideration applied to fashion from a generation that will forever be the foundation of youth culture street style.”

That’s just one example of how hip-hop and high fashion have become deeply intertwined since the 1970s. In the 1980s and ’90s, hip-hop stars Run-DMC, LL Cool J, Salt-N-Pepa and others put their personal style on display. And today, no one bats an eye at rap star Kanye West’s much-hyped Yeezy line of apocalyptic-themed apparel and accessories for Adidas or clutches their pearls when rapper ASAP Rocky stars in advertisements for Dior Homme or Calvin Klein.

While the hip-hop community has long been enamored with the fashion world, the appreciation has been reciprocated in recent years as luxury labels including Balmain and Saint Laurent embrace hip-hop artists and mimic some of their aesthetics.

Hip-hop’s breakthrough fashion players

Since the late 1970s, hip-hop has made its way from insurgent music genre to the defining cultural movement of our times. But it hasn’t been entirely about the music.

To look at fashion today is to understand that hip-hop has been an undeniable influence on the way we dress. From Run-DMC’s endorsement of Adidas and Sean Combs’ launching his own fashion label to Kanye West and Pharrell embracing the world of high-end European fashion, here’s a look at the players who led the way.

ALSO: How hip-hop fashion went from the streets to high fashion

Here’s why Compton is so important to the hip-hop storytelling of Kendrick Lamar

LIKE THE FICTIONAL Yoknapatawpha County where writer William Faulkner set many of his stories, the rapper and lyricist Kendrick Lamar, who is nominated for seven Grammy Awards including album of the year, has populated his hometown of Compton with stories, plots, images and recollections that map the contours of his city.

Mixing fact and fiction with rhythm and sound, Lamar since his debut mixtape in 2009 has become South L.A.’s most crucial storyteller, and he’s harnessed the area’s most notable corridor, Rosecrans Avenue, in service of those narratives.

Whether on tracks including “Backseat Freestyle,” “Keisha’s Song (Her Pain)” or “Money Trees” or in the videos for his tracks “Compton State of Mind” (a riff on Jay-Z’s “Empire State of Mind), “King Kunta” and “i,” Lamar locates his creative world in the area in which he was raised.

ALSO: How Rosecrans Avenue became L.A. hip-hop’s Main Street

Explore Rosecrans Avenue and listen to its music, a tour of L.A. rap’s Main Street

Compton’s Most Vaunted: Who would deserve a spot on a Rosecrans Walk of Fame?

The rise of XXXTentacion underscores rap’s fraught battle with the law

AS JAHSEH ONFROY TURNED 19 early last year, his rap career hit a new peak.

The Florida native’s homespun brand of hip-hop had already attracted a fierce cult following and the attention of major labels as his single “Look at Me” blew up. The lo-fi track with blistering (and unprintable) lyrics had clocked Soundcloud and Spotify plays by the millions, sending it up the Top 40 based almost entirely on its number of streams.

When a spat with superstar Drake, who was accused of co-opting the rhythm of “Look at Me,” put the single on mainstream radars, Onfroy — who performs as XXXTentacion (that’s “X -X -X -Ten -Tah -See -Ohn ”) — found himself the face of a movement of Soundcloud rappers disrupting hip-hop.

But instead of celebrating his cultural moment with friends and fans, he was sitting behind bars in Broward County Jail, charged with multiple felonies for allegedly beating and strangling his then-pregnant ex-girlfriend in 2016. Onfroy, who pleaded not guilty, has also been accused of false imprisonment and witness tampering and faces up to 30 years in prison.

And yet, like many rappers before him, Onfroy found that being jailed didn’t hurt his career. His fame skyrocketed after his release on bail in March.

He collaborated with Diplo and Noah Cyrus. Shows across the country sold out. And his melancholy debut album, “17,” put out by Empire Distribution, reached No. 2 on the Billboard 200 chart. Co-signs from ASAP Rocky and Kendrick Lamar (“Listen to this album if you feel anything. raw thoughts,” Lamar told his nearly 10 million Twitter followers) added to his surging popularity. . . . .

By October the rapper had scored a distribution agreement reportedly worth $6 million between his own imprint and Caroline Records, which is part of Capitol Music Group, home to artists such as Sam Smith, Katy Perry, Mary J. Blige and Beck. It was the same month that allegations of sexual harassment were made public against Harvey Weinstein, breaking open the #MeToo movement. Would the cultural reckoning happening in Hollywood and the media affect the rise of XXXTentacion and other emcees facing serious charges?

All this stuff is coming out about Harvey Weinstein and Hollywood guys, but in the hip-hop community it’s just put under the rug.

— Talyssa Lee

Pharrell and Chad Hugo redefined hip-hop’s sound, now they’ve put out a N.E.R.D response to Trump

Jay-Z had big hits before “I Just Wanna Love U (Give It 2 Me),” his playful 2000 single that pleads with a woman for “that funk, that sweet, that nasty, that gushy stuff.”

There was “Hard Knock Life (Ghetto Anthem),” which sampled the musical “Annie” and reached No. 15 on Billboard’s Hot 100. And there was the sleek “Can I Get A…,” which drove 1998’s “Rush Hour” soundtrack to platinum sales.

But it was arguably “I Just Wanna Love U,” with its danceable groove and its chorus sung in a goofy yet cool falsetto, that turned the once-gruff Jay-Z into a cuddly mainstream pop star. And behind that transition was Pharrell Williams and Chad Hugo, known then as the Neptunes, the production duo who over the next decade would go on to help redefine hip-hop’s sound — and propel its reach into R&B and pop.

Williams and Hugo, two proud music nerds from Virginia Beach, spent the 2000s working as the Neptunes with virtually anyone they wanted to, from the Clipse to Busta Rhymes to Britney Spears. They also had a freewheeling side project, N.E.R.D before Williams embarked on a successful solo career. (That goofy yet cool falsetto? That was his.)

By 2016, Williams had become so ubiquitous — having won Grammys, scored an Oscar nomination and hit No. 1 on his own with the secular-gospel jam “Happy” — that somebody thought it would be a good idea for him to produce an album by the country group Little Big Town.

But rather than pursue whatever other wacky offers came his way after that, Williams unexpectedly reformed N.E.R.D with Hugo and their childhood friend Shae Haley to make a record that reflects the political and social upheaval of the last 18 months — and shows these adventurers are still devoted to exploring fresh territory.

“No_One Ever Really Dies” ... is a furious response to the election of President Trump, to police shootings of unarmed black men, to the malfeasance of corporations.

Five sonic leaps that changed the sound of hip-hop

With their skittering grooves and their preference for original sounds over recognizable samples, Pharrell Williams and Chad Hugo, as the production duo the Neptunes, helped remake hip-hop’s sonic identity in the late 1990s and early 2000s. (See related story: “They Redefined Hip-hop’s Sound, Now Chad Hugo and Pharrell Have Put Out a N.E.R.D Response to Trump.”) But they’re hardly the only producers responsible for such a shift. Here are five evolutionary leaps from the genre’s history.

1997

The Notorious B.I.G., “Mo Money Mo Problems”

This exuberant club track came out a few months after the Notorious B.I.G. was killed in March 1997. But “Mo Money Mo Problems,” produced by Puff Daddy and Stevie J, also represented the birth of the classic Puff Daddy m.o., in which he’d “take hits from the ’80s,” as he put it in a later song, and make it “sound so crazy.”

The song that took the West Coast’s so-called G-funk sound fully into the mainstream, “Nuthin’ but a ‘G’ Thang” used a radically laid-back beat.

Rolling Loud’s SoCal debut underscore’s hip-hop’s cultural dominance

A GUST OF RED confetti dusted thousands of bodies lost in the feverish bounce that was Migos’ set on opening night of the Rolling Loud Festival in San Bernardino on Dec. 16.

The Atlanta trio’s barrage of brain-rattling trap anthems capped a day that had already seen impressive sets from Lil Yachty, Jaden Smith, Playboy Carti, Ski Mask the Slump God and Gucci Mane in the hours before.

Arriving in Southern California for the first time since debuting in Miami two years ago, the two-day blowout underscored hip-hop’s position as the most dominant force in pop music with a deeply stacked lineup of chart-toppers, underground rap talent and buzzy acts percolating on the internet.

Nielsen Music confirmed what pop radio and streaming figures already knew: Hip-hop was being consumed more than any other genre and with hip-hop dominating this year’s Grammy nominations and inspiring a spate of film and TV projects, Rolling Loud offered a potent, and important, showcase of how far the genre has evolved in just the last few years.

Jay-Z [became] the first emcee to top Coachella’s bill, and rappers have headlined nearly every year since.

Why hip-hop, once ostracized in clubs, is ruling the festival circuit

HEAVING MOSH PITS. Vocalists with candy-colored hair and gender-bending jewelry, who stage-dive into crowds of shrieking young fans. Lyrics about chemical indulgences and all-night partying, with guitar-streaked ballads of regret, lost love and nihilism.

Welcome to the new hip-hop festival.

“Rappers are the new rock stars. If you want high-energy concerts with crazy mosh pits, you find that at rap shows today,” says Tariq Cherif, co-founder of the roving Miami-based hip-hop festival Rolling Loud.

“It’s guys in tight jeans wearing chokers and crazy hair,” adds Rolling Loud co-founder Matt Zingler. “It’s way more appealing than a DJ.”

Zingler’s last point — about rappers supplanting DJs — may hold an answer to a question that has bedeviled the festival business since the rise of American EDM.

With a new wave of hip-hop utterly dominant on streaming platforms, a genre once shunted to the sidelines of festivals or overpriced bottle-service clubs may finally be coming into its own as a festival phenomenon.

I’ll bring up the top streaming songs...and it goes ‘Hip-hop, hip-hop, pop-R&B, hip-hop, hip-hop, hip-hop. It dominates the top of the charts.

— Jim Lidestri, BuzzAngle founder

The moment N.W.A changed the music world

OF THE MANY BIG BANGS that have transformed rap over the decades, N.W.A’s “Straight Outta Compton” is one of the loudest.

It was a sonic Molotov cocktail that ignited a firestorm when it debuted in the summer of 1988. Steered by Dr. Dre and DJ Yella’s dark production and Ice Cube and MC Ren’s striking rhymes, then brought to life by Eazy-E’s wicked charm, the record fused the bombastic sonics of Public Enemy’s production with vicious lyrics that were revolutionary or perverse, depending on whom you asked.

The world hadn’t heard anything like it before. Radio stations and MTV refused to add the title song to their playlists. Critics didn’t get it, couldn’t see past the language, or, worse, refused to acknowledge it as music. Politicians even launched attacks, going to great lengths to condemn the music and its creators.

The 2018 Grammy nominations are overdue acknowledgment that hip-hop has shaped music and culture worldwide for decades. With the launch of this ongoing series, we track its rise and future.

N.W.A were to hip-hop what the Sex Pistols were to rock — and really, what’s more punk than having a name that dared to be spoken or written in full, and music that incensed a nation?

Everything in the world came after this group. ... We changed pop culture on all levels. Not just music. We changed it on TV. In movies. On radio. Everything.

— Ice Cube on N.W.A’s influence