There may be a hero in this real-life drama, but the happy ending isn’t written yet

First of two parts

If screenwriter Babs Greyhosky was penning this episode of her life, the young woman she calls her “goddaughter” would be at home with her children right now.

But managing the action in the real world isn’t as simple as a storyline on TV.

It began with a phone call from a panicked young woman who was locked up at the sheriff’s station in La Crescenta. Deputies had raided her South Los Angeles house looking for drugs and guns linked to an Altadena gang. They hauled her and her boyfriend off to jail, and sent her five children to foster care.

Greyhosky calls it the end result of “a very bad mistake” — wrong address; no drugs or guns; just flakes of wall plaster and an empty shotgun shell.

That would be the TV version. Real life is more complicated, with fuzzy facts and imperfect players. If there’s a hero in this story, Greyhosky might be it. But the role comes with a cost: her innocence.

::

Fifteen years ago, Greyhosky answered a call in the Writers Guild of America newsletter for volunteers to mentor teenagers in Juvenile Hall. She gave the girls a writing assignment. Only one, Shanell Walton, bothered to try it.

Shanell was 16 and seven months pregnant; a streetwise bully with a bad attitude. She’d been a ward of the court since she was 11, when she got tired of living alone on the streets and called authorities on her crack-addict mother.

But Shanell wouldn’t stay in foster homes, and cycled in and out of Juvenile Hall. “I bonded with gang members back then,” she told me. “They were the only people looking out for me.”

She joined Greyhosky’s writing class “mostly because I was bored,” she said. “I figured she was just a white person trying to make herself feel better by mentoring this young black girl. I wasn’t going to fall for her drama.”

Greyhosky laughs now at the notion that she would be the dramatic one. Shanell was funny and loud and fearless and raw; she seemed to court trouble, but kept pushing forward. Greyhosky saw passion where others saw anger.

They began collaborating on writing projects, in long raucous sessions at Greyhosky’s home in the San Fernando Valley. The projects foundered but the relationship flourished.

Greyhosky was an only child, “with parents who would have thrown themselves in front of a bus to protect me,” she said. “And here was this child who’d never had anybody to lean on. I wasn’t trying to be a savior. I just wanted to be consistent; one person she could count on.”

And count on her Shanell did. “Babs got me my first apartment, paid for my childcare.… She made me want to prove I could do something good.”

What she did wasn’t always so good. Greyhosky didn’t withhold judgment — or love.

Months would go by without them seeing one another. But Shanell always knew how to find the woman who had become the closest thing she had to a mother.

“Nothing changes with Babs,” Shanell said with the awe of a person who never knows what chaos the next day will involve. “She’s still got the same phone number. She still orders the same thing for lunch — salad and ice tea. I could show up at her house, sit on her patio and know before long, she would be there.”

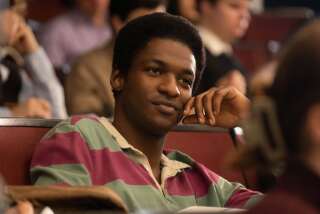

The affection between the women is clear, as I sit with them in the conference room of a Beverly Hills counseling center where Greyhosky is training to be a therapist. Shanell, now 30, is brown-skinned and heavy-set, with eyes that glow and a smile that beams. Babs is trim and intense, with a probing manner and schoolteacher’s mien. She’s an adjunct professor at USC and has been a television writer for 25 years.

They correct each other’s mistakes and finish each other’s sentences. “Babs knows me better than anybody, except maybe my kids,” said Shanell. “We have a very honest relationship. I could tell her anything…. Except when I was pregnant again.”

I see a daughter deflecting a mother’s criticism: Shanell laughs, but looks chagrined. Greyhosky shakes her head and purses her lips.

Five kids. That’s a sore point between them. “She’s a good mother, a very good mother,” Greyhosky insists. “But five children?”

That must seem like a pile of obstacles to a middle-class woman who never had children.

Shanell offered neither explanation nor defense. Her children — now 13, 7, 6, 4 and almost 1 — are what she has to show for a life well-lived. And all she can think about right now is getting them out of foster care.

“I want my children home with me,” she said.

::

The story that drew me into their drama began with deputies tearing through her front door in the middle of the night, rousting her from bed with flashlights and guns.

Her boyfriend, who was on parole for a crime committed 10 years ago, was taken to jail after deputies found an empty casing for a shotgun shell.

“Something from a yard sale,” Shanell said. “I kept thinking this must be some mistake.”

Her children watched while police searched the house — cutting into mattresses, she said, emptying drawers, mixing piles of clean and dirty laundry.

She was angry now, yelling at the deputies, cursing them out. “I was very unruly,” she acknowledged. “How could they get away with this?”

They handcuffed her, “and then I got scared,” she said. “They said they found a $2 piece of cocaine on top of my television set.” She was arrested for child endangerment. A social worker showed up and took custody of the five kids.

Three days later, Shanell was released from jail; no charges, no court appearance, no bail. The jailer told her the chip of “cocaine” was tested and found to be flaking plaster. Shanell’s boyfriend was apparently the warrant’s target, in a case involving a series of gang-related shootings in Altadena and Pasadena.

I can’t confirm Shanell’s account of the raid or the evidence deputies found. The Sheriff’s Department refused to comment; reports are sealed and the investigation is ongoing.

“But doing a search warrant in the middle of the night when we know there are children involved is not something we take lightly,” Sheriff’s Sgt. Debra Herman said.

Greyhosky finds it all hard to fathom. It’s been six weeks since Shanell was cleared of charges, and her children are still in foster care. Greyhosky has made their return her mission.

“It almost feels like a conspiracy,” she said. “And I’m not big on conspiracy theories.”

Still, she badgers the lawyers and social workers, bombards her friends with outraged appeals. And she helps Shanell keep her gas tank filled for the endless rounds of foster care visits — her children have been separated and placed with different families.

She just keeps thinking about Shanell’s teenage daughter, the one she was pregnant with in Juvenile Hall. As police swept through the house, the girl was holding her baby brother, shielding him from the light and noise.

Her biggest concern? Would the chaos be over in time for her to get to school? They were prepping for state tests at Gompers Middle School, and she wanted to do well this year.

Instead, she wound up in a stranger’s home. And didn’t get back to school for weeks.

Tuesday: Shanell Walton heads to court, determined to show she deserves her children.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.