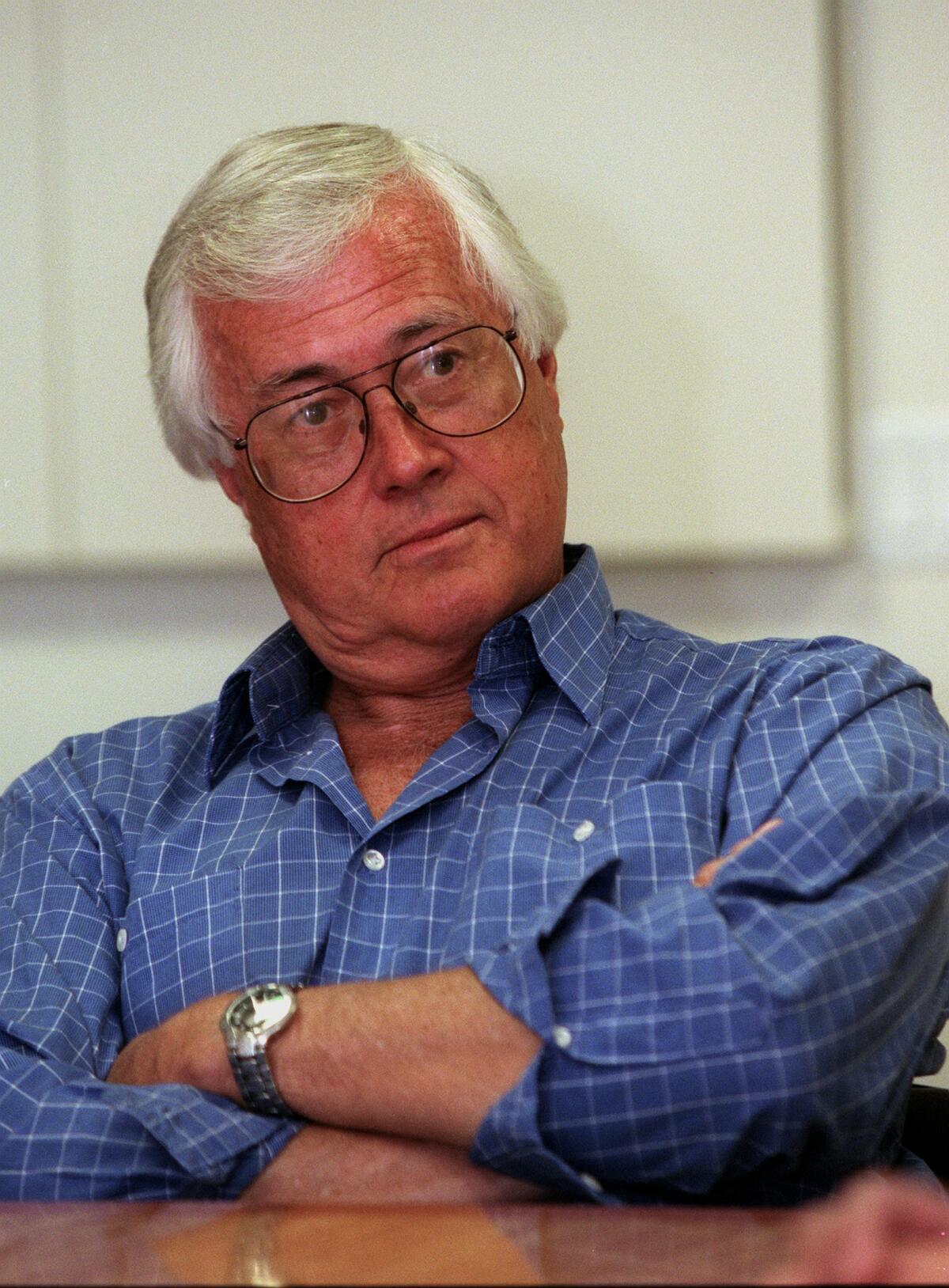

Allan Burns, revered writer known for ‘The Mary Tyler Moore Show,’ dies at 85

Seth Freeman caught his big break when the legendary television writer Allan Burns asked the newcomer to join his team for “Lou Grant,” the 1977 drama showcasing the lives of a gruff but lovable city editor and his staff at a fictional Los Angeles newspaper.

They previously worked together on one of Burns’ spinoff series years back when Freeman was still experiencing the growing pains of finding his voice. It had been Freeman’s first prime-time assignment and he felt his writing wasn’t funny or good enough because other senior writers kept rewriting his work.

Freeman wasn’t seasoned enough to know this was normal in showbiz. In hopes of finding guidance, he asked Burns out to lunch. Freeman confessed he didn’t think his work on “Rhoda” was great and that he was still learning the craft. Without missing a beat, Burns responded, “Well, so am I.”

“That was quintessential Allan, always a student of the craft,” Freeman said.

After an award-winning career, Burns died Jan. 30 of Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia at his home in Los Angeles, his son Matt said. He was 85.

Burns’ road to success in the television industry wasn’t a linear path and he wasn’t a stranger to bizarre Hollywood experiences. He started his career as an NBC page and was later hired as a script analyst for the broadcast company’s now-defunct Comedy Writer Development Program. In a way, Burns realized the experience was useful in his quest to write.

Burns had trouble finding his next job after he was fired from NBC, so he switched gears and leaned into his cartooning skills. He took a freelance gig illustrating and writing humorous greeting cards. His work eventually led him to work for Jay Ward Productions, where he wrote for characters in the cult hit comedy series “The Bullwinkle Show.” He was also unexpectedly tasked with creating a mascot for Quaker Oats’ Cap’n Crunch cereal.

After he left the production company in 1963, Burns finally started writing scripts with his colleague Chris Hayward. They helped create the sitcoms “My Mother the Car” and “He & She.” Years later, Burns worked with James L. Brooks and wrote the comedy-drama “Room 222,” set in a fictional urban high school in L.A.

Burns cemented his name in the industry when he cocreated “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” with Brooks. The show, which debuted on CBS in 1970, made TV history for its progressive portrayal of womanhood in America at a time when feminism was still planting its seeds. The show’s main character, portrayed by Mary Tyler Moore, introduced viewers to a single woman in her 30s who landed a job as an associate producer in a Minneapolis TV newsroom.

Comfortably single and unafraid to stand up to her gruff newsroom boss, Mary Richards splashed onto television screens at a time when feminism was still putting down roots in America, a woman who charged through the working day with equal parts humor and raw independence.

“[Burns] and Jim were very forward-thinking in terms of gender, bringing in women writers, women producers, women on staff way before that became the politically correct thing to do,” said Ed. Weinberger, a writer and producer who worked on the show. “I think that’s a major contribution to our business. Allan was at the forefront of that.”

Burns told the Writers Guild Foundation in 2012 that CBS officials had a “corporate heart attack” when they heard his and Brooks’ initial idea for the show: a fiercely independent divorced woman who worked as a stringer columnist in Los Angeles. But Moore and her husband, Grant Tinker, loved the idea.

“Divorce isn’t a sin anymore,” Burns told network officials. “It isn’t an awful, awful thing. Everybody knows somebody who is divorced. ... They’ll understand it.”

CBS still wasn’t convinced. A research executive told them there were four things American audience wouldn’t tolerate: “New Yorkers, Jews, people with mustaches and divorce.”

The show aired for about seven years and won 29 Emmy Awards and 22 Golden Globe Awards.

Former First Lady Michelle Obama said as a young girl she drew inspiration from the character.

“She wasn’t married. She wasn’t looking to get married. At no point did the series end in a happy ending with her finding a husband — which seemed to be the course you had to take as a woman,” Obama said in a 2017 interview.

Matt said he believes his father was ahead of the curve with his feminist vision because of his childhood. Burns’ father died when he was 9, and the boy saw his mom take a job as a secretary for the mayor of Baltimore to support them. They later moved to Honolulu because Burns’ older brother was stationed at Pearl Harbor and could help them financially.

Burns’ impact permeated beyond the television screen. He served as a board member for the Music Center, the Jazz Bakery and the Rape Treatment Center of Santa Monica Hospital Medical Center, known now as the Rape Foundation. At the foundation, he and Freeman created three short films for high schools and college programs aimed to educate men and women about rape and help reduce the number of victims.

“You feel so helpless about crime,” Burns told The Times in 1990. “But this is something we can attack. Women have the right to say ‘no.’ ‘No’ means ‘no.’ It doesn’t mean maybe or try harder.”

Freeman said: “At Allan’s core was a sense of social justice, which was reflected in everything he did. He gave a great deal of his time and creativity to encouraging, educating and inspiring in particular those who had fewer advantages. And he did this quietly, steadily, modestly.”

Burns is survived by his wife, two sons and five grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.