Op-Ed: Sanders calls Clinton’s fundraising ‘obscene,’ but it’s more nuanced -- influence isn’t corruption

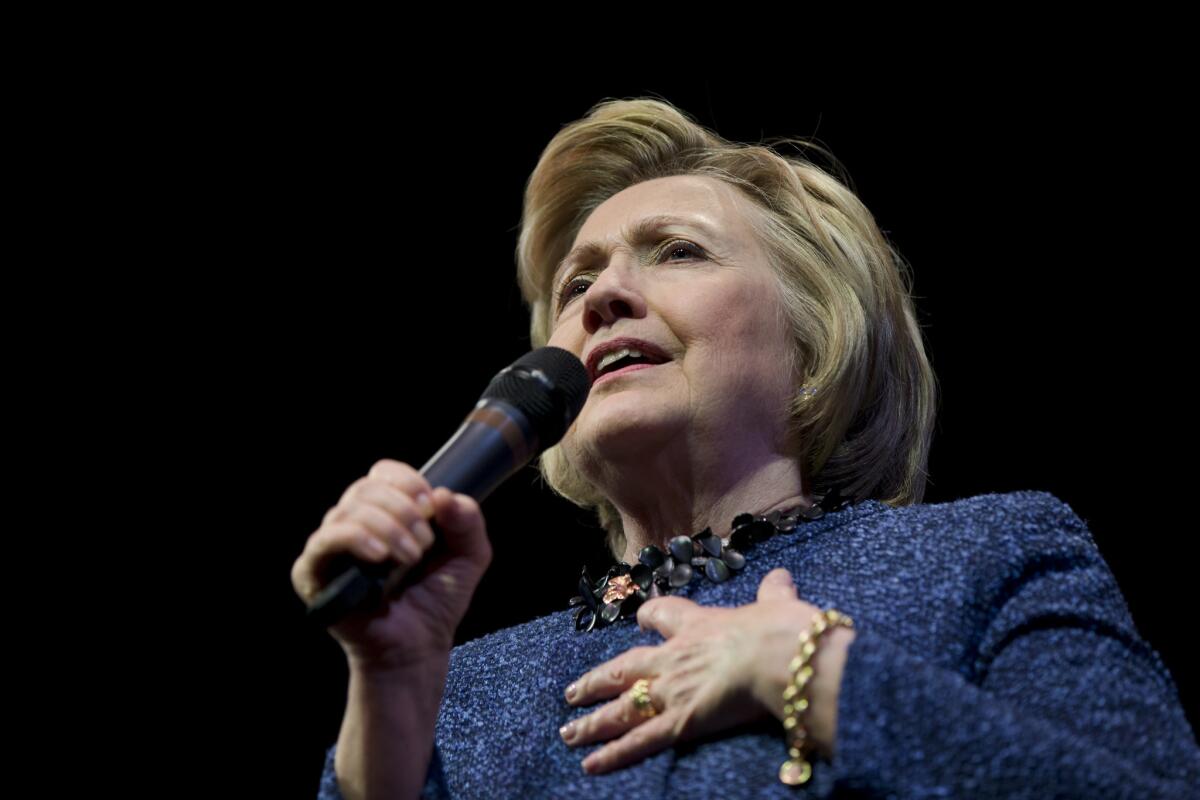

Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton speaks during a campaign stop, Wednesday, April 20, 2016, in Philadelphia.

Despite Bernie Sanders’ repeated accusations, there’s no real evidence that Hillary Clinton has been corrupted by large campaign contributions. But that’s not to say donors haven’t influenced her thinking and priorities. Lodged in the gap between Sanders’ attacks and Clinton’s rejoinders lies the truth about big money in politics.

Anyone who has heard two minutes of a Sanders stump speech knows he rails against a “corrupt campaign finance system” that benefits the rich and powerful, and boasts of the support he gets from millions of individuals making small donations.

Sanders and his supporters call Clinton’s fundraising “obscene.” Using fuzzy math (such as counting all the donations bundled by lobbyists who have had oil companies as clients), the Sanders campaign asserted that Clinton took millions in donations from the fossil fuel industry.

More recently, the Sanders campaign’s lawyer issued a letter suggesting, without evidentiary support, that Clinton or her supporters were breaking the law when they solicited six-figure donations in a joint fundraising operation with the Democratic National Committee and state political parties. In fact, while that fundraising strategy might be troublesome, it does not appear to violate any of the many porous rules set by Congress, the Federal Election Commission, or the Supreme Court. Nor is there any evidence, despite the belief of some ardent Sanders supporters, that Clinton has somehow been bribed to do the bidding of big donors.

Still, Clinton struggles to explain why, when she opposes the influence of big money on politics, that no one should worry about her super PAC money and massive donations. During a New Hampshire debate she said “you will not find that I ever changed a view or a vote because of any donation that I ever received.” I bet Clinton actually believes this statement. But it glosses over the more subtle way money influences politics.

Clinton still struggles to explain why, when she opposes the influence of big money on politics, that no one should worry about her super PAC money and massive donations.

The unending money chase demanded by our privately financed system of campaigns skews how candidates spend their time and what views they hear. When you spend hours every day interacting with those wealthy enough to make four-, five-, six- and even seven-figure donations, you can’t but help to have your priorities influenced by their concerns.

Connecticut Sen. Chris Murphy, who has spent hours a day on the phone asking for donations, spoke at a Yale conference a few years ago about how this “soul-crushing” amount of fundraising skews priorities. “I talked a lot more about ‘carried interest’ inside of that call room than I did in the supermarket,” Murphy said, referring to a controversy about how little tax wealthy hedge fund managers and others pay on certain investment income.

A 2013 study found that the wealthy are much more likely than the rest of us to report having personal contact with a senator or representative. And it turns out that the 1% have very distinct views on public policy. The same study reported that the very wealthy are much less likely than the general public to support policies such as raising the minimum wage, providing substantive unemployment benefits, or expanding public health insurance programs.

Money has influence even before it is donated. A senator taking a position in favor of Internet gaming, for example, has to ask whether that stance will cause casino mogul Sheldon Adelson to unleash millions against him. Likewise, every senator from New York, including Clinton from 2001 to 2009, knows that staking out positions against Wall Street can close wallets or send money streaming to their opponents.

This is a deeply troubling campaign finance system, one which is slipping dangerously toward plutocracy. But it doesn’t take a bribe for money to matter, a lot.

Richard L. Hasen is a professor of law and political science at UC Irvine and the author of the book “Plutocrats United: Campaign Money, the Supreme Court, and the Distortion of American Elections.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.