Op-Ed: Election conspiracy theories, an American staple

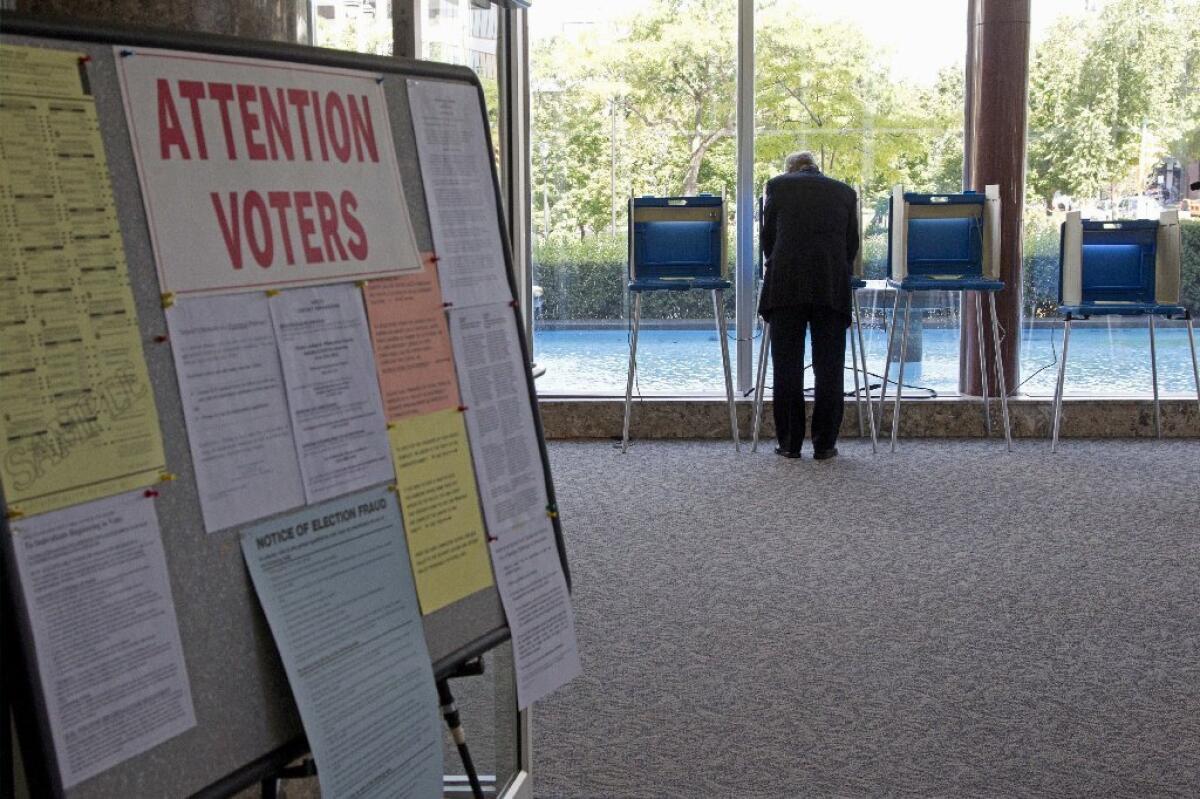

During this 2014 midterm election season, mainstream and social media have inundated voters with tales of schemes and skulduggery. Whatever the result of Tuesday’s election, many will believe that the process was rigged, the outcome is fraudulent, and they were cheated. The pattern of conspiracy theories is unfortunate but familiar.

How pervasive is the belief that American elections will be swayed by improper means? Very. In 2012 we conducted surveys to gauge what Americans thought about the integrity of the system. Just before the election, we asked a national sample of respondents about the likelihood of voter fraud if their preferred presidential candidate did not win. About 50% said fraud would have been very or somewhat likely. When asked if someone was using “dirty tricks” in the election, about 85% believed that some candidate, campaign or political group was.

These sentiments are not driven by members of one party or the other: Near equal numbers of Republicans and Democrats (between 40% and 50%) said fraud would be very or somewhat likely. Each side believes that if they lose, cheating is to blame, and they believe it about equally. Nobody likes losing, but it appears hard for about half the country to accept that they lost fair and square.

Such beliefs can have serious consequences. The Democrats faced close and bitter defeats in the 2000 and 2004 presidential elections. Following the resolution of the 2000 presidential election, about a third of the country (mostly Democrats) believed the election of George W. Bush was fraudulent. And even years after the fact, almost 40% of Democrats believe that fraud swung the outcome in Ohio, the decisive state in 2004.

Responding to the belief that their voters had been suppressed in 2000 and 2004, Democrats made herculean efforts at voter registration and mobilization in 2008 and 2012. These efforts contributed to the successful election and reelection campaigns of Barack Obama. Republicans saw these efforts as attempts to subvert the system and stuff ballot boxes. As a result, Republican governors and state legislatures instituted tougher restrictions on voting, including shortened early voting times and voter identification requirements.

In response to these Republican efforts, Democrats have accused Republicans of manufacturing phony assertions of voter fraud as part of a wide-ranging conspiracy to curtail Democratic voters’ access to the polls. This spiral of hostility is bound to continue. One irony here is that the Democrats broadly believed that voter fraud was used against them in 2000 and 2004, but now contend Republican efforts to decrease voter fraud is a form of voter fraud.

But focusing on the last few elections obscures how routine conspiracy theories are in the electoral process. In addition to surveying the public, we also examined accusations of voter fraud made in letters to the editor of prominent newspapers. What we found was a regular stream of voter fraud accusations over more than 120 years that seemed to recycle endlessly.

Just as there were concerns that powerful “corporate masters” had purchased George W. Bush’s election, there were similar concerns that powerful corporate interests had purchased the 1888 election for President Benjamin Harrison. Just as some people think Democrats conspired with the IRS to target conservative political groups going into the 2010 election, people in 1893 believed that the Democrats at that time were conspiring with tax officials to rig elections. Throughout American history, many groups have been accused of tampering with elections, including Republicans, Democrats, Catholics, Mormons, government workers, unions, socialists, corporations and foreign countries.

If you awaken on Nov. 5 to find that your favorite candidate or party didn’t win and you’re convinced that fraud is to blame, you’ve got a lot of company.

Conspiracy theories, especially electoral conspiracy theories, have been an American staple for as long as we can tell. And perhaps they serve a purpose. After all, beliefs so popular and widespread may have some truth behind them. And even if they turn out to be false, they may be useful. It may take heightened sensitivity to deter dirty tricks and recover quickly from defeat.

Joseph E. Uscinski and Joseph M. Parent are associate professors of political science at the University of Miami and authors of “American Conspiracy Theories.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.