Decline in opioid deaths is tied to growing use of overdose-reversing drug, CDC says

Prescriptions of the overdose-reversing drug naloxone are soaring, and experts say that could be a reason overdose deaths have stopped rising for the first time in nearly three decades.

The number of naloxone prescriptions dispensed by U.S. retail pharmacies doubled from 2017 to last year, rising from 271,000 to 557,000, health officials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Tuesday.

The United States is in the midst of the deadliest drug overdose epidemic in its history. About 68,000 people died of overdoses last year, according to preliminary government statistics reported last month. The previous year, there were more than 70,000 such deaths.

“One could only hope that this extraordinary increase in prescribing of naloxone is contributing to that stabilization or even decline of the crisis,” said Katherine Keyes, a drug abuse expert at Columbia University.

About two-thirds of U.S. overdose deaths involve some kind of opioid, a class of drugs that includes heroin, certain prescription painkillers and illicit fentanyl.

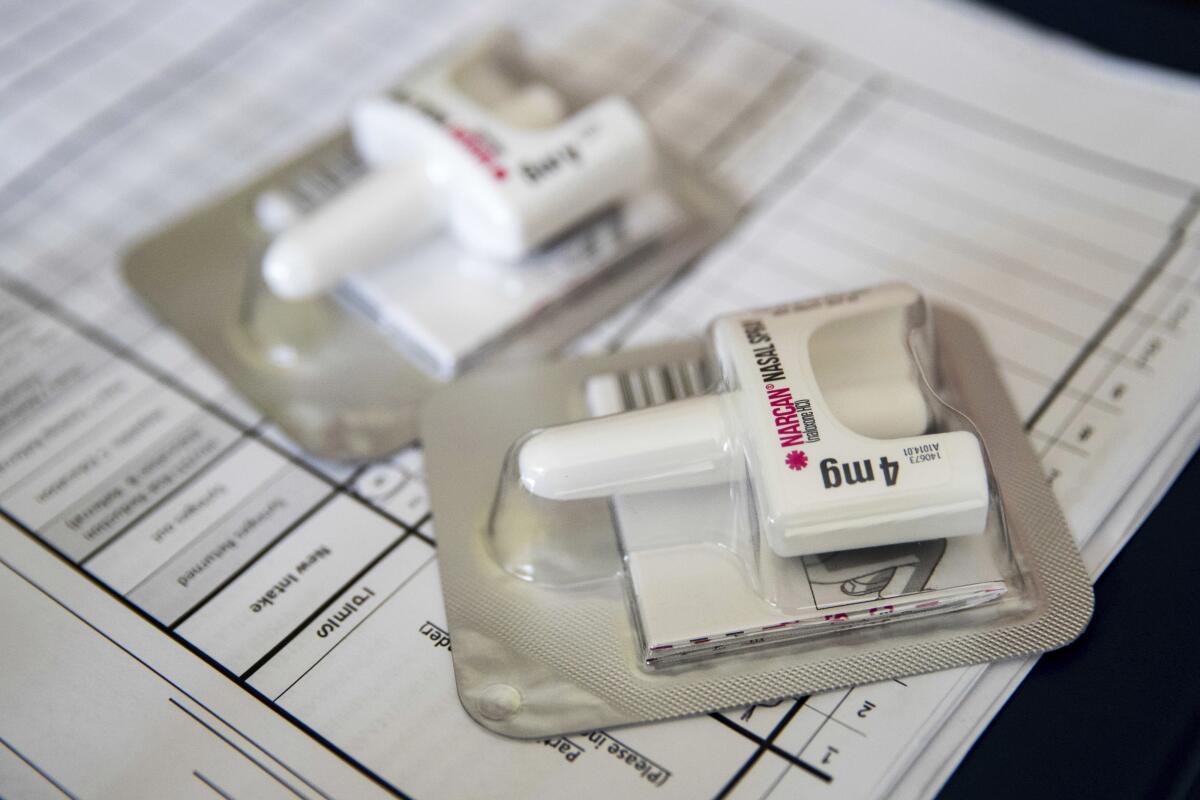

Opioid overdoses can be reversed with naloxone. The drug restores breathing and brings people back to consciousness. It first went on sale in 1971 as an injection; an easier-to-use nasal spray version, Narcan, was approved in 2015.

Local, state and federal officials have embraced naloxone as a lifesaving measure. Some cities and states have standing orders that allow pharmacies to give it out without a doctor’s prescription, and officials have tried to put it into the hands of virtually anyone who might encounter a person overdosing, including drug users, police and even librarians.

CDC researchers noted there were fewer than 1,300 naloxone prescriptions dispensed in 2012. That means the number grew more than 430-fold in six years.

Health officials said pharmacies should be giving out even more.

“We don’t think anybody is at the level we’d like to see them,” said Dr. Anne Schuchat, the CDC’s principal deputy director.

The CDC report is based on data from IQVIA, a company that tracks healthcare information, and looked at prescriptions from more than 50,000 retail pharmacies across the country. It included both prescriptions written by doctors for specific patients and those filled under the broader standing orders.

The report offers only a partial picture, however, since only about 20% of naloxone was sold to retail pharmacies in 2017, according to an earlier government report.

Still, it’s the CDC’s first close look at where most retail dispensing is happening. The agency provided data for about 2,900 of the nation’s 3,100 counties and parishes.

The researchers found it was most commonly dispensed by pharmacies in cities and the South.

Experts said the findings likely reflect a number of factors. More naloxone is likely prescribed in places where more people are using opioids and where policies increase access.

For example, 11 of the 30 counties with the highest rate of naloxone dispensing were in Virginia. Virginia has a lower overdose death rate than most other states, but it allows anyone to buy naloxone without a prescription and has taken other steps to encourage its use.

The CDC recommends that naloxone be prescribed to patients who are getting high-dose opioids and are at risk for an overdose. It noted, however, that only one naloxone prescription is written for every 69 high-dose opioid prescriptions.

Another finding: The number of high-dose opioid prescription painkillers dispensed fell to about 38 million last year, from nearly 49 million the year before. In all likelihood, that also contributed to the decline in overdose deaths last year, Schuchat said.

Stobbe is a medical writer for the Associated Press.