Tyler Hilinski’s family rebuilds their lives around youngest son’s football dreams

The water on the lake is smooth this afternoon, hardly a ripple, the calmest the couple can remember. They bought the red brick house that sits on a small peninsula with panoramic views six months ago, seeking a refuge that could provide them peace they no longer had within.

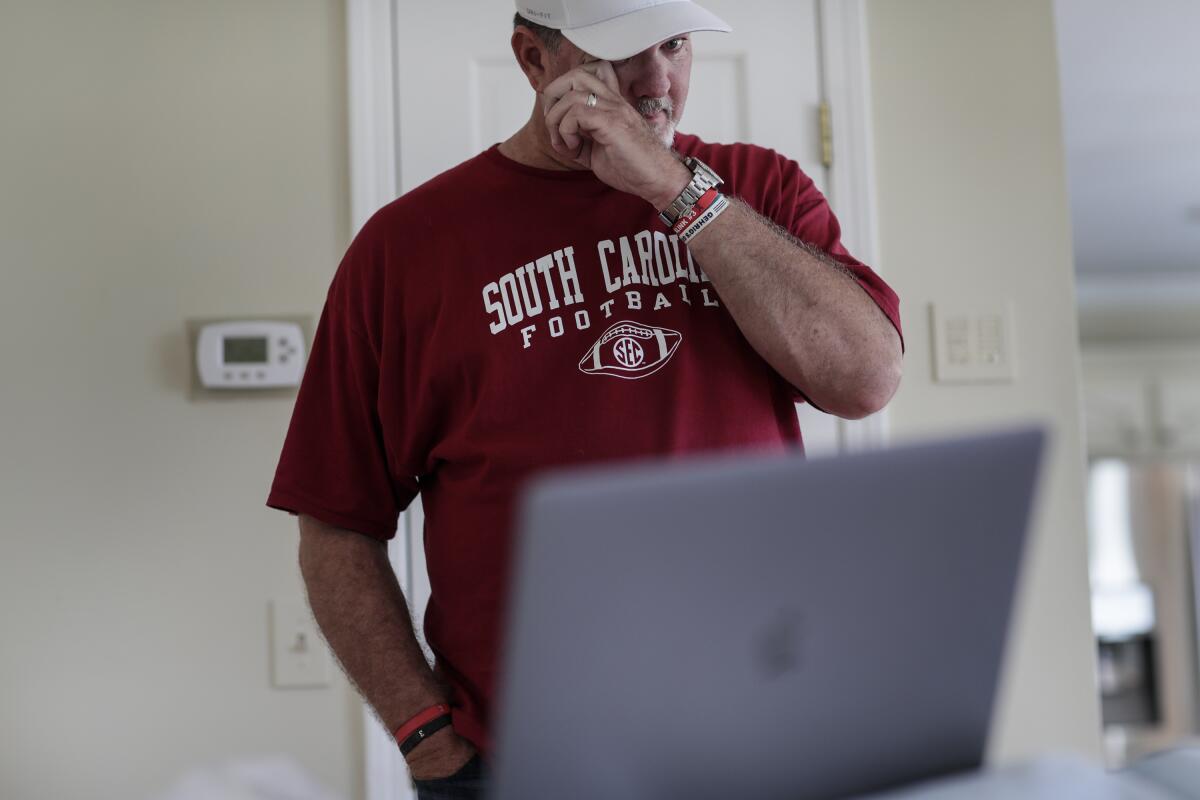

Mark and Kym Hilinski are always moving. To the boat for a quick spin around Lake Murray and a meal. To Ryan’s football practice over in Columbia. To the post office to send thank-you notes all over the country. Back to their new house, which they are pretty sure will never feel like a home, not without Tyler.

But they’re sure going to try. A construction crew has arrived, getting going on a renovation that should span the entire fall. The Hilinskis plan to be busy traveling the Southeast, doing what else but following another son’s football dream. They have already come so far from their native Southern California, so why not go ahead and start over?

Like most everyone around town, the contractor wants to talk about only one thing: Will the Hilinski’s youngest son, a true freshman, win the job to be the South Carolina Gamecocks’ backup quarterback?

The parents of Tyler Hilinski said that an autopsy revealed that the Washington State quarterback had chronic traumatic encephalopathy at the time of his suicide in January.

“I watched the spring game on TV,” he says, “and I thought Ryan looked great.”

By this point, Mark expects such banter. “He could redshirt either way,” he offers. “His mom would prefer he redshirts all four years.”

There’s laughter, but it’s not a joke.

“They’re not going to announce the backup until after the second scrimmage,” Mark says.

“That’s when we are in Hawaii,” Kym chimes in from the kitchen.

They leave for the islands the next day, and there is much to do. Some of Tyler’s ashes will be packed into travel-size bottles because they never know if airport security will stop them and create an awkward situation. The first time they scattered the ashes of their sweet middle son — the former Washington State quarterback who took his own life in January 2018 and sent shockwaves across the football landscape — was at a lighthouse on the island of Kauai where the family used to vacation.

The University of Hawaii football team has invited them to share Tyler’s story as part of the family’s mission with Hilinski’s Hope, their charity that promotes mental health awareness and reducing the stigma among college athletes, so it feels like a good time to bring Tyler back.

One by one, the speakers climbed on the dais and shared their memories of the departed.

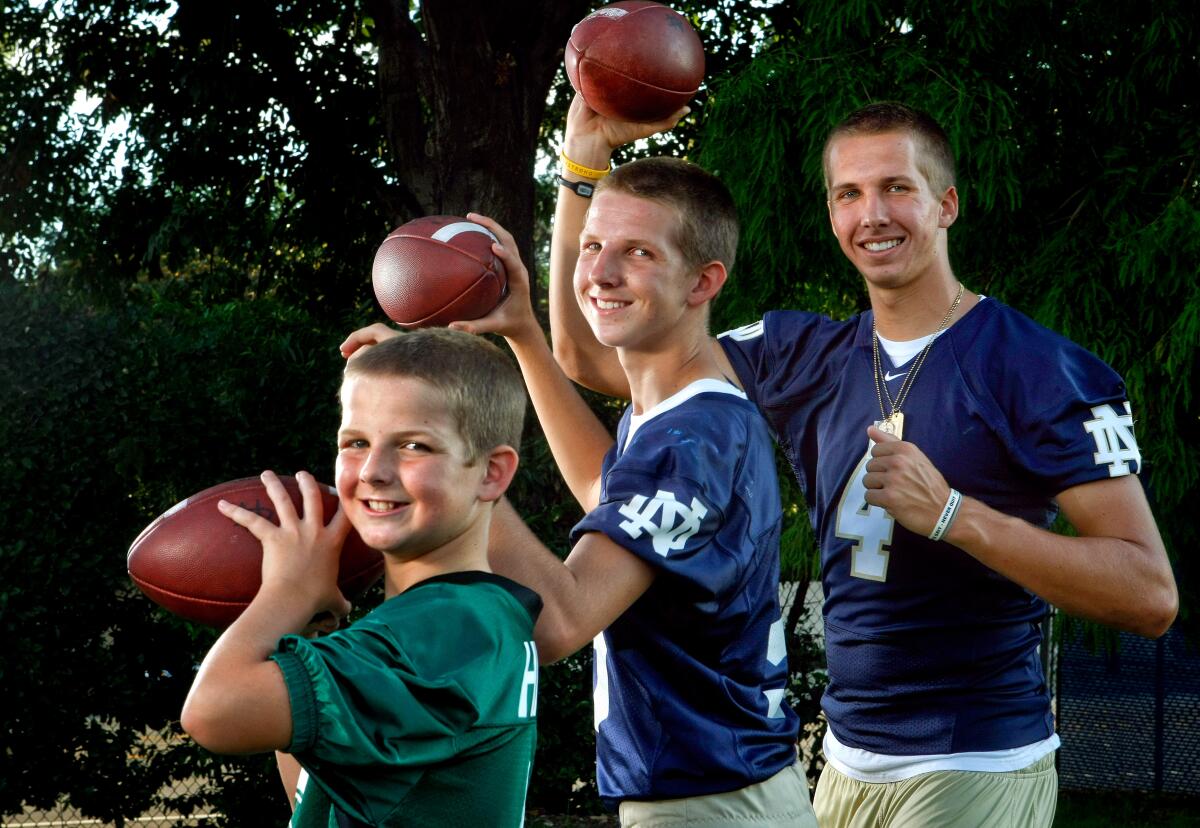

When Mark talks to groups, he does not focus on what factors may have contributed to Tyler’s silent suffering, like the revelation that the quarterback had been living with the tau protein build-up in his brain known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy or CTE. Mark just tells them about Tyler, the second of his three sons who all had a chance to play every position in every sport but gravitated to the glamour position in the country’s most gloried game.

Kelly, Tyler and Ryan each grew to become the prototype — tall, and blond-haired and blue-eyed like their mother — and they loved leading a team. Tyler worked to arrive at the part of his story that should have been the height, being the assumed starter for a Pac-12 Conference program known for gaudy passing numbers, and then went to a place so dark that he did not want to experience it. That is the part that nobody can understand, the part that leads Mark and Kym to believe their boy must have been sick.

Even after doing his talk so many times, it is never routine for Mark, a bear of a man who emotes effortlessly. The rawness does not go away.

“You have to almost race yourself to sleep,” Mark says. “In other words, you get to the end of the day, and it’s not a normal shutdown, OK? Have dinner at 7? Or have a drink and watch a movie or a show, whatever is your normal thing. Go read? And it feels like we just get on this roller coaster, you know, and sleep is here. And you just hit it as hard as you can. Because that’s your only break.”

They think about the boys, and the boys think about them. On Saturday, Kelly, who has also moved to the Columbia area, will take his Medical College Admission Test. The same day, a few hours away in Charlotte, N.C., Ryan will run onto the field for the first time as a Gamecock against North Carolina, and maybe he’ll take his first college snap.

These are pressure-packed times for the Hilinski boys, and their parents have tried to lighten the load.

“They should have a fulfilled, wonderful life,” Kym says, “and losing their brother, I’m sure it’s going to take a long time for them to even truly believe that, and I hope they do believe it and enjoy their lives. So we help them. We got jet skis. And for a couple weeks, we were having a blast, you know, going as fast as we could, going around in circles. And then after a while, I’m like, you know, let’s remodel the house. Do we really need to remodel our house?”

The questions they ask themselves have no answers. So they make changes. Kelly and Ryan now have matching lighthouse tattoos on the underside of their right forearms. Kelly and Tyler both wore the jersey No. 3, and, while No. 4 was Ryan’s number at Orange Lutheran High, he will wear No. 3 in college too.

The house on the lake will look different soon. But one item that will stay is a decorative plate that hangs outside by the front door. It says “Forever To Thee,” a line from the South Carolina alma mater, and, “Forever To Three.”

::

So, just imagine, Mark Hilinski says as he leads a tour of the second floor, a bedroom that has a patio feel, with a big king bed, and waking up to the sun coming up over the water.

It’s nice to have a chance to create something. After Tyler died, Kym went back to the family home in Claremont once; she could not bear to go again. With the two older boys at college, they had already downsized, moving with Ryan to Irvine and renting out their home.

When Ryan stuck with his commitment to play at South Carolina, even after his dream school, Stanford, offered him late, his parents were already planning to put the Claremont place on the market and join him here. While staying in California would have kept them close to family and friends, and allowed Mark to remain a part the technology company he founded, the Hilinskis were almost relieved to get to uproot.

They did not want to have to revisit all the Pac-12 stadiums where they watched Tyler play, if they could avoid it. Ryan agreed that wasn’t necessary.

“We came here sort of running away, sort of running to see how Ryan does,” Mark says. “Just push it all into the fire and see what comes out.”

The flames of the past are persistent, though. Mark could spend his entire day beating himself up, and often does. On a muggy August evening with rain clouds hovering over the lake, he picks apart his priorities at the time he first heard that Tyler was missing and that a report would have to be filed with the Pullman, Wash., police.

“My thought is, he’s got a whole year to prepare for his dream job, running a Pac-12 team, and the first thing is going to be, well, we have this incident of him missing, and the [public relations] of that being published,” Mark says.

He fumed over the idea that Washington State coach Mike Leach could hold that against Tyler, who never missed a practice. In fact, they’d later find out, that very day he had texted the wide receivers about meeting to work out.

Mark has learned so much about mental illness and what his son must have been facing. He regrets another one of his early instincts, from a visit he made to the Cougars the day after Tyler died.

“It sounds ridiculous, but I wanted the team to know he loved them,” Mark says. “That he wasn’t weak. That this wasn’t, ‘I’m tired, I’m just gonna leave.’ Don’t be mad at him. I was protecting him. Why is that? Well, I didn’t want them to think less of him in death. Wow. Talk about how strong stigma can be.”

Today, Mark won’t say that Tyler “committed” suicide. He prefers “die by” because Tyler had an illness, and “you don’t commit cancer,” he says.

That frame of mind keeps him from becoming angry at Tyler for not seeking help before he pulled the trigger on the AR-15 semi-automatic rifle he had stolen from friends after an afternoon of skeet shooting. That was the first time Tyler had ever shot a gun, and his family will never know what made him take it and turn it on himself in a closet three days later.

“At what point is it mental illness?” Mark asks. “You might remember the 1966 University of Texas shooting, the father [of the shooter] finds the letter in the typewriter saying, ‘I’m going to kill everybody on campus tomorrow at eight o’clock. When you get me, please tear my brain apart and figure out what’s wrong with me because I know it’s wrong. And I can’t stop myself.’

“I don’t know how much different that is to what Tyler did. Well, Tyler was so sweet, he wouldn’t hurt anybody else. You mean like his family, like his brothers, like his mom who can’t sleep? He’s sick.”

After months with no possible answers for Tyler’s illness other than the diagnosis of CTE, a new occupant of Tyler’s Pullman apartment found his phone hidden in a vent. The Hilinskis tried every password they could think of before convincing a company to help them unlock it.

What was found only prompted more questions.

In the hours before he died, Tyler deleted Mark and Kym’s contacts, as if he didn’t want the temptation of asking to be saved.

They found no suicide note, or explanation, or keyword search that offered a clue, only the numbers of the six-digit password that Tyler had set, which phonetically spelled:

S-O-R-R-Y-Y

::

Before they leave for Hawaii, Kym has four packages and eight cards to mail to people who have donated to Hilinski’s Hope, which has raised about $400,000.

The donations come from all over the globe, usually in $3, $33, $333 increments, a nod to the family’s favorite number. She addresses and writes the notes by hand.

The days can feel so long, there’s no reason to rush through it. Kym stays heavily caffeinated with “Monster” tallboys to avoid going to sleep.

“Because if I dream, I go to the closet,” she says.

All she wanted after Tyler died was somebody, or some thing, to blame.

In the spring of 2018, she and Mark were driving through the Southeast with Ryan on what they called their “SEC road trip” when they got a phone call from the Mayo Clinic, where they had sent Tyler’s brain for an autopsy.

The doctor told them that Tyler had CTE, a degenerative brain disease that has been linked to the repetitive hits sustained by playing football. Tyler was 21 but his brain looked like that of a much older man.

Kym thought back to her younger days as a football mom. She always had wished the boys could be covered in bubble wrap.

We made a pact when we were younger. It was, ‘Hey, if I don’t make it to the NFL, you’re going to make it to the NFL,’ and vice versa. I’m just trying to carry on that dream for Tyler.

— Ryan Hilinski on pact he made with his older brother, Tyler

“Tyler would go from linebacker to quarterback,” she says. “I remember one time having to jump out of the stands and going down to the coach and saying, ‘Listen, you gotta let my son rest.’ But Tyler was a gamer. He wanted to help the team win.”

Did football take her son? Kym wanted to jump to that conclusion. But then there was her youngest, 17-year-old Ryan, excited to visit these SEC schools who were all offering a scholarship.

Even if Mark and Kym were willing to consider asking him to quit the sport, Ryan would not have listened. Tyler’s death only made him more resolute that he was going to be a successful quarterback.

“We made a pact when we were younger,” Ryan says. “It was, ‘Hey, if I don’t make it to the NFL, you’re going to make it to the NFL,’ and vice versa. I’m just trying to carry on that dream for Tyler.”

When the news went public that Tyler had CTE, USA Today posted a video with the title, “A hard truth: Football killed Tyler Hilinski.”

The Hilinskis did their own research. They talked to top doctors and neurosurgeons who have studied CTE. What they found is that there was no data to support a causal connection between CTE and suicide. There was also no evidence of a stronger likelihood for getting CTE based on genetics. The fact was, the large majority of former football players who have been diagnosed with CTE posthumously did not die by suicide.

“The data doesn’t add up,” Mark Hilinski says. “There would be more suicide. I’m not saying it didn’t have something to do with that. I’m saying that there’s nothing that shows me that it had something to do with it.”

Nobody lives with America’s emotional turmoil regarding the physical toll of football more intimately than the Hilinskis. But they did not ask to be at the center of this storm, and they don’t want to pick a side.

More research is being done to better understand CTE, and, in the meantime, they are choosing to act on what they do know — that high-level athletes need more education about mental illness.

“The games are what’s going to be hard,” Kym says. “It’s going to be emotional because I’m going to see a college kid at quarterback wearing No. 3, and that’s Tyler, right?”

On Saturday in Charlotte, it will be Ryan. He won the backup job behind senior starter Jake Bentley in camp, which makes him the likely starter next season — a place the Hilinskis know all too well. They wish they didn’t have to care, but here they are, once again wrapped in the drama and competition.

No matter what happens, they’re in this together.

“We have to build off each other’s happiness,” Ryan says. “If one of us isn’t happy, we all know it.”

Mark and Kym work to give Ryan and Kelly a chance at youthful innocence. They agreed that they had to stop crying in front of the boys. For a while, Kym would go on long walks around the lake to shield them.

She wonders how she’ll get through the next four years. There will be new traditions and cheers, an indoctrination to South Carolina spirit. She even bought a goofy-looking cowboy hat she swears she never would have worn to a Pac-12 game.

Kym also plans to continue with one of her personal touches.

Before her sons’ games, she writes them a note. This summer, she penned one leading into Ryan’s first scrimmage, hoping to remind her youngest of what’s important.

“Big Ryan,” she wrote. “I’m always so happy to see you, whether it’s watching you play video games, watch TV, talk with you or watch you play the sport you love. So, this afternoon when you see me in the stands, remember how happy I am because you are just yards away. Have fun today, laugh, smile, breathe. I’m so proud of you, Ry, and so is your Big T — let’s go #3. Love you allll much, Mom.”

::

If you or someone you know is exhibiting warning signs of suicide, seek help from a professional and call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.