U.S. hostage Luke Somers killed in Yemen during rescue attempt

In the predawn hours Saturday, a team of elite U.S. commandos stepped off a tilt-rotor aircraft into the desolation of central Yemen, intent on rescuing American photojournalist Luke Somers from his militant captors.

The team of 40 Special Operations forces trudged more than six miles amid hills and scrub brush to a heavily fortified compound in Shabwa province that U.S. intelligence specialists had pinpointed as the location where Somers was being held.

The mission was an urgent one: The Al Qaeda affiliate that was holding Somers, 33, threatened last week to kill him if unspecified demands were not met by the Obama administration.

“We had good intelligence he would be killed the next day,” said a Defense official, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “It was either act now or take the risk. And we weren’t going to let the deadline pass.”

With officials in Washington watching, the troops drew near the remote compound under the cover of darkness, according to an account provided by Defense officials.

Their surprise attack was foiled, however, by a militant who was outside, a Defense official said. The extremists began firing wildly, sparking an intense firefight. Over the next 10 minutes or so, U.S. forces killed six militants, but one was seen going into the building where Somers and another hostage were being held, and exited soon after.

While inside, the militant shot the captives, a senior Pentagon official said. The special operators, who quickly overcame the extremists, went inside to find Somers seriously wounded, as was the other hostage, South African teacher Pierre Korkie, whose wife had been told he was just a day from being freed.

“There is zero possibility that the hostages were victims of crossfire,” the senior official said. “This was an execution.”

The forces, after about half an hour in the compound, moved the wounded hostages to the aircraft and flew them to an awaiting U.S. Navy ship, the Makin Island, off the coast of Yemen. Surgeons and medics worked on the two men on the way to the ship, but one died en route and the other on the operating table, the officials said.

The failed raid was the second attempt in 10 days by U.S. special forces to save Somers. On Thursday, the Pentagon acknowledged a Nov. 25 operation that freed eight captives — including citizens of Saudi Arabia, Yemen and Ethiopia — but Somers and several other foreigners apparently had been moved days before it took place, Yemeni officials said.

In the video of him obtained last week, militants warn against “any other foolish action” by Americans, and Somers pleads to be freed by whatever means possible.

Somers’ death comes after the beheadings of other American journalists in recent months by Islamic State militants who have captured large parts of Iraq and Syria. Another failed rescue attempt was made this summer in search of one of those victims, Steven Sotloff.

“There is no excuse for the brutality and inhumanity of groups like AQAP [Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula] and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant,” said Army Gen. Martin Dempsey, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, using another name for Islamic State. “We will relentlessly seek to protect our citizens and punish those who threaten us.”

In releasing a video statement vowing to kill Somers if their demands were not met, Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula seemed to be taking a page from Islamic State’s playbook. While the Al Qaeda group has a history of kidnapping Westerners, experts say it’s plausible that the attention generated by Islamic State’s videos of beheadings might have added impetus to follow suit.

“There’s certainly a good deal of contagion involved in all of these insurgencies and terrorist organizations,” said James Dobbins, a senior fellow and security expert at Rand Corp. “There’s a lot of imitation, a lot of back and forth, and it’s more intense now because of the Internet.”

The tactic may have been sharpened by a macabre rivalry or one-upmanship between Islamic State extremists and Al Qaeda factions. For them, analysts say, the hostage-taking followed by video threats has for the moment become what they see as an effective means for generating attention, one of their principal aims. It is probably directed less at the U.S. than at people closer to home for recruiting and other purposes.

“It’s the competition between terrorist groups in the Middle East that has heightened this,” said Bruce Hoffman, a terrorism expert at Georgetown University. “Of course, this type of behavior is the essence of terrorism. It generates fear and anxiety as well as publicity and attention.”

Yet the failed attempt to rescue Somers from extremists has renewed questions about American intelligence and special forces capabilities, given that there have been other unsuccessful efforts to extract hostages and that the U.S. government’s position on not negotiating with or paying ransoms narrows its options.

Korkie’s death was made all the more tragic by the militants’ agreement to release him Sunday, according to Gift of the Givers, a South African humanitarian group.

“‘The wait is almost over,’” the group had told his wife, its founder said in a statement. The Al Qaeda group kidnapped Korkie and his wife, Yolande, a humanitarian worker, last year. She was freed in January without payment of ransom, the aid organization said, though it would not comment on whether ransom was involved in the negotiations to release Pierre Korkie. The charity said Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula had demanded about $3 million in exchange for letting him go.

Experts say such missions are notoriously difficult, noting that it took years for the U.S. to find Osama bin Laden.

In Somers’ case, Hoffman said, “I was actually heartened and impressed that we had this kind of intelligence that we could mount a credible rescue attempt. It didn’t save Mr. Somers, but there were hostages there — and Western hostages,” he said of the earlier raid that freed eight people. “This has to also have, at least, a chilling effect on terrorist leaders.”

President Obama and the Yemeni government approved the latest attempt to rescue Somers that morning, a Defense official said on condition of anonymity. Time to plan the operation was short, but the planning was “thorough,” the official said.

“The callous disregard for Luke’s life is more proof of the depths of AQAP’s depravity, and further reason why the world must never cease in seeking to defeat their evil ideology,” Obama said in a statement. He also vowed that those who harm U.S. citizens will feel “the long arm of American justice.”

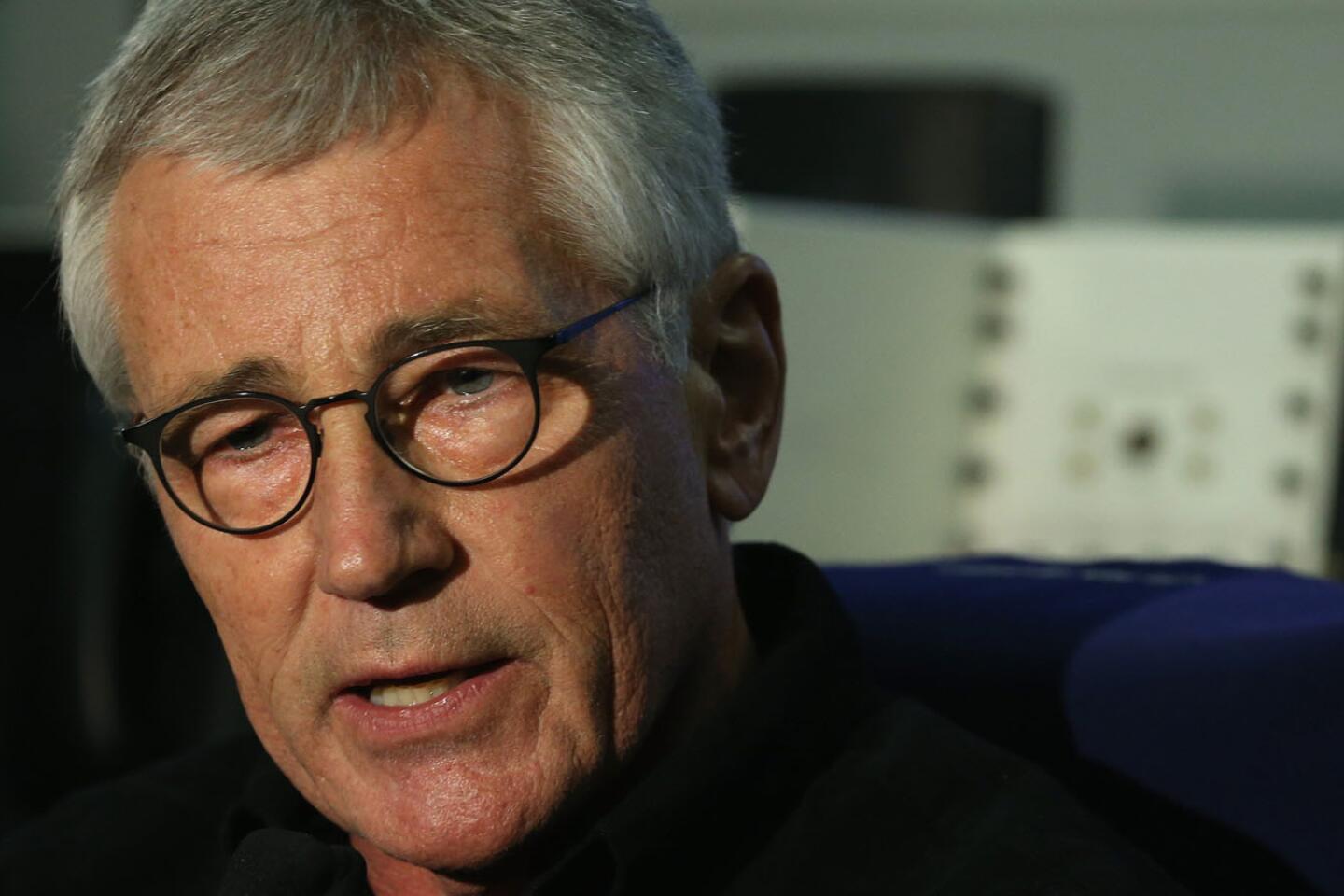

Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel said in Afghanistan that the mission was “extremely well-executed,” but that it carried challenges that ultimately couldn’t be overcome.

There were no injuries to any of the U.S. troops in the rescue operation and no casualties to Yemeni civilians, the senior official said.

Somers graduated from Beloit College in Wisconsin in 2008, according to Jason Hughes, a campus spokesman. He had expressed an interest in the Middle East during his college years and studied abroad in Egypt, Hughes said.

Years later, he went to Yemen to teach, said Tik Root, a Vermont native who worked as a journalist alongside Somers in Yemen in 2012. Somers’ photography became a second profession as he grew more attached to Yemeni culture, Root said.

“Luke was a very passionate and thoughtful person, and I think one of the things that shone through was his love of Yemen and Yemeni people,” Root said. “It was definitely a second home, or a home, to him.”

Somers worked with the National Dialogue Conference, an organization dedicated to improving the lives of Yemeni citizens.

Root said when he last saw him last year, Somers said he was considering leaving the country.

Two weeks later, he was abducted.

Times staff writers Hennigan reported from Kabul and Cloud from Washington. Staff writers Don Lee in Washington; James Queally in Los Angeles; Laura King in Dubai, United Arab Emirates; Robyn Dixon in Melbourne, Australia; and special correspondent Zaid Ali in Sana, Yemen, contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.