Column: California’s illegal immigration fight is back, and so are the political pitfalls for Republicans

Few topics have been as incendiary in California as illegal immigration, with intense arguments about whether those who cross borders are a reminder of the American dream or a sign of its demise.

Those past debates — most visible during elections in 1994 and 2010 — may offer some insight into the issue’s political rewards and risks.

For starters, neither effort sprang from measurable public anger. In 1993, a Los Angeles Times poll found only 2% of voters surveyed cited immigration as the state’s top problem. Jobs and the economy were more pressing, they said.

Nor were things boiling over in late 2009, when 3% of respondents picked illegal immigration as the biggest problem in a poll by the Public Policy Institute of California.

Column: There’s not a California congressional district with Republicans in the majority »

And yet Republican leaders of the time insisted otherwise.

In late 1993, then-Gov. Pete Wilson said that “our state is facing a crisis in illegal immigration.” In the spring of 2010, GOP gubernatorial candidate Steve Poizner warned of “the strain” the issue was causing. Both men ultimately built campaigns around an effort to deny government services based on citizenship.

Fast forward to May 2016, just before the state’s current debate, and a remarkably similar snapshot: Only 6% of likely voters in a PPIC poll saw illegal immigration as the biggest issue. Five times as many said it was jobs and the economy.

More than a dozen California Republicans suggested otherwise when they sounded the alarm on illegal immigration last week with President Trump.

“It is a crisis — that’s the point we’re at in California,” Assemblywoman Melissa Melendez (R-Lake Elsinore) said at a White House meeting, with Trump sitting next to her and nodding in agreement.

Coverage of California politics »

Statistics from U.S. Customs and Border Protection suggest otherwise. When comparing the past seven months to the same time period in 2017, there’s been no growth in the total number of adults and families detained along California’s portion of the border. The only growth — and it’s been sizable — is in the number of unaccompanied children crossing.

Unlike today, the 1994 and 2010 clashes took place in the midst of California recessions — hardly the case now, with the state’s jobless rate at its lowest recorded point since 1976.

This time, the conflict feels more instinctual than economic. The president’s push for more immigration raids sparked California Democrats to write a state law limiting local law enforcement’s cooperation. That prompted a federal lawsuit and now, friend-of-the-court briefs filed by California communities on both sides.

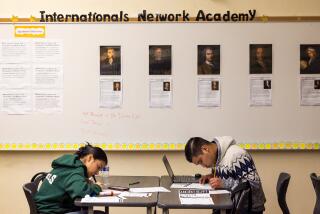

A more conciliatory approach is being taken by Rep. Jeff Denham (R-Turlock). He’s pushing for a path toward citizenship for so-called Dreamers, the young immigrants left in limbo by the cancellation of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA. Denham enlisted the help of two fellow California Republicans in the House, and the approach aligns with middle-of-the-road voters.

The party’s leadership, though, is dusting off the get-tough strategy of 1994 and 2010. John Cox, the GOP candidate for governor endorsed by Trump, boasts of “leading the opposition” to the sanctuary law in a TV ad. And he describes the immigrants as “illegal aliens,” a phrase that invokes the polarizing fights of the past.

The hard line on illegal immigration worked in 1994. But it’s haunted the party since, as public opinion shifted and Latinos grew in size and power. So why try it again?

Because Republicans, now only 25% of the registered electorate, need to keep their base voters motivated and unified. Otherwise, the dynamics of a top-two primary — where the biggest clusters of votes win — favors Democrats.

History suggests it might be a clever game plan in June when more conservative primary voters tend to show up, but calamitous come November.

Follow @johnmyers on Twitter, sign up for our daily Essential Politics newsletter and listen to the weekly California Politics Podcast

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.