L.A. Phil’s YOLA players are goodwill ambassadors near Fukushima

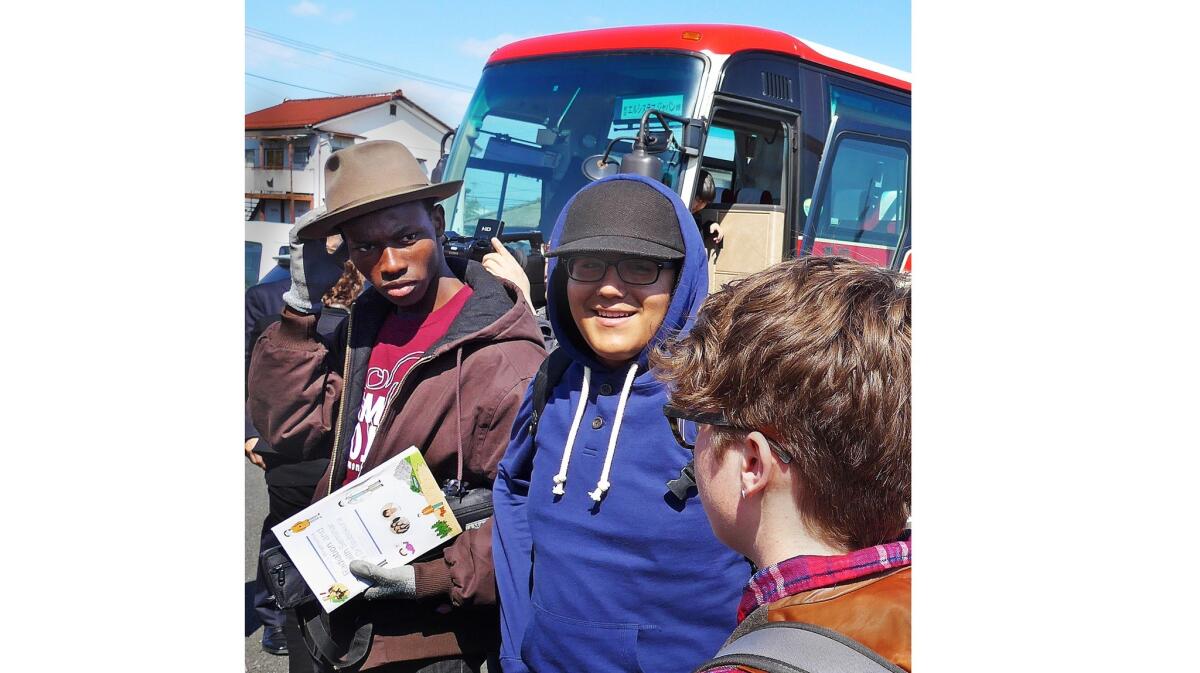

A sleek bullet train pulled into a city in northern Japan recently with 15 Los Angeles teenagers aboard. They looked like typical school kids everywhere, in the uniform of T-shirts, hoodies, jeans and sneakers. The city likewise appeared unremarkable, although the snow-capped mountains in the distance were pretty.

But this was the city of Fukushima. And the students were members of YOLA, the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s Youth Orchestra L.A. patterned after Venezuela’s El Sistema music education program.

Fukushima has become an international synonym for disaster four years after a 9.0 offshore earthquake, terrifying tsunami and meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station. The YOLA contingent was on its way to the coastal town of Soma to spend two days rehearsing with a local children’s orchestra in preparation for a high-profile public rehearsal in Tokyo with Gustavo Dudamel, the L.A. Philharmonic’s music director.

Never having been to Asia, the Angelenos hardly knew what to expect. The first thing they were handed on the long bus ride to Soma was a booklet in English with cartoon illustrations explaining the effects of radiation on the body, an attempt to comfort as well as minimize the current danger we would face.

The booklet seemed to imply a not very convincing cartoon unreality. That unreality continued for a while.

Soma, a city of 35,000, might also have been mistaken for fairly normal, at least if you didn’t cross Highway 6 and try to get to Matsukawa-ura Bay, where fishing was once rich. The coastal region stretching more than 100 miles is now barren. The debris of fallen houses and the boats washed ashore has been cleared away. New grass has grown. But nothing is there.

The main part of town, on higher ground not reached by the tsunami, was badly damaged by the earthquake. It has been rebuilt. Still, nearly 500 lives were lost. Incomes have been ruined. The Japanese outside of Fukushima Prefecture are hesitant to buy the local agriculture, dubious of government radiation testing. Only certain kinds of fish are deemed safe to eat.

Among the many daunting challenges has been providing a sense of normality to children, and nothing seemed more natural than beginning El Sistema in Japan here three years ago.

Japan boasts one of the world’s most advanced systems of music education. Its Suzuki method alone has populated not only the country but the world with a generous supply of excellent string players. Music appreciation is part of the curriculum of all Japanese schools from the earliest grades.

Music’s role in the recovery effort, moreover, has been significant. Two weeks after the earthquake and tsunami, the Sendai Philharmonic rallied to give a benefit concert amid the rubble of the region’s largest city. The orchestra also traveled to Russia on a thank-you tour for Russian aid.

In fall 2013, at the instigation of the Lucerne Festival, artist Anish Kapoor and architect Arata Isozaki designed the world’s first inflatable concert hall, a gorgeous bubble called arc nova, for the flood victims. It was installed for a few concerts each fall and attracts international artists. Around the same time, Soma opened a lovely new 430-seat concert hall as the most telling symbol of the city’s rejuvenation.

The Municipal Concert Hall is also home to the Soma Children’s Orchestra and Chorus, and that is where the American and Japanese students gathered. This was the third trip culturally and geographically for a select few of the older and more experienced YOLA musicians and the farthest afield.

The Japanese students, who outnumbered the Americans 4-to-1, tended to be younger and less musically experienced. The executive director of Friends of El Sistema, Yutaka Kikugawa, told me on the train to Fukushima that the first visit to Japan in 2008 by Dudamel and the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra (now the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra) was the inspiration for Japan’s El Sistema.

In 2012, Kikugawa used his experience as a goodwill ambassador for UNICEF to create the first Japanese programs, locating them in the part of the country most in need. Parents took to the project immediately, especially pleased that the program would keep their children indoors when the radiation levels were elevated outside. The Sistema style of learning music in children’s orchestras goes against the Japanese tradition of private practice.

Maybe even more important is a sense of community for the 3,000 kids who now participate citywide in Soma’s Sistema. These are not necessarily disadvantaged youth. But all were affected by the disaster (even if the smallest are too young to remember it) and lost loved ones.

Cultural and age differences, along with a language barrier (the Japanese students have a smidgen of English), might have meant music would be the only common ground. Many of the Japanese children wore school uniforms and were initially shy. The YOLA players took over most of the first-chair duties; their younger Japanese counterparts dutifully followed them.

Most of the long hours of work were devoted to the last movement of Dvorák’s Eighth Symphony. Soma conductor Yohei Asaoka and YOLA’a new conductor, Juan Felipe Molano, shared the podium at rehearsals, with Asaoka emphasizing technique and Molano trying to bring out more emotion. Both faced the obvious obstacle that this music was beyond the capacity of such a group.

But Soma is not an ordinary place, and this was not an ordinary situation. Behind the placid facade of the city are unmistakable signs of hardship, such as the temporary structures for those displaced (and likely to be for quite some time).

There were oddities. A small music store displayed CD bins marked happy music and ultra-happy music. All the offerings looked like similarly cheesy Japanese pop, but the ultra-happy music was more expensive.

The second morning the YOLA students took a sobering trip to the areas of devastation. Driving past a strip of new car dealerships and fast food restaurants, we suddenly turned into eerie Odaka, one of nine ghost towns within a 15-mile radius of the reactors. People had evacuated suddenly, leaving toys and bicycles in the yards. It might have been a set for “The Twilight Zone.”

At dinner that night, the students had difficulty putting into words how they felt about an experience for which there are few adequate words. But they had access to music as a means of expression and afterward demonstrated new urgency as section leaders.

This may have been when they won over their hosts. Young Japanese girls displayed giggly crushes on the older American guys. A flute player’s selfie stick, which he had bought at LAX, was a huge hit.

The concert with Dudamel on Sunday morning in Suntory Hall in Tokyo, the day of the L.A. Phil’s final concert of its Asia tour, may not have accomplished the technically impossible. But in a mere 35 minutes of rehearsal, Dudamel got the players to reach remarkably deep inside themselves.

Fukushima presents a set of seemingly unsolvable problems, such as how to dispose of several hundred square miles of radioactive topsoil. But in Tokyo, you get the sense that many wish the problem would just go away. It won’t, and when kids play Dvorák as if their lives depend on getting it right, the moral imperative becomes palpable.

The short program ended with Dudamel conducting the orchestra and the Soma children’s chorus in a performance of the Mozart motet “Ave Verum Corpus” dedicated to those who sacrificed to help in Fukushima. The spirit of Soma and Mozart was, for several moving moments, the same phenomenon.

After that it was back to being kids, clowning around as they gathered their things in a reception room. An outstanding YOLA clarinetist, Edson Natareno, told me that he had gastritis and had no idea how he had done. He had, like an old trouper, played with a beautiful grace. Dudamel had singled out Daniel Egwurube, whose flute solo was spectacular.

In rising to the occasion of Dvorák, 15 YOLA students became invaluable Los Angeles ambassadors of goodwill. The names of the 13 accomplished others are Marcy Areliano, Moses Aubrey, Joas Espinzoa, Jacopo Esquivel, Laura Garcia, John Gonzales, Miguel Guendoley, Kevin Im, Alice Morales, Karen Ramos, Juliana Rodriquez, Sam Rosas and Blanca Tinoco.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.