‘Tale of the Heike’ elegantly retells Japanese epic

The Tale of the Heike

Translated by Royall Tyler

Viking: 734 pp., $50; illustrated

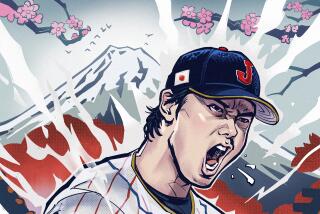

An epic retelling of the 12th century Japanese civil war, “The Tale of the Heike” (Heike Monogatari) has provided the source material for Kabuki, Noh and bunraku plays, novels and films. Printmakers from Yoshitoshi and Chikanobu to the contemporary artist Hideo Takeda have illustrated it. Graphic novelist Stan Sakai referred to it in his long-running “Usagi Yojimbo” series.

In the late 12th century, the emperor was a divine figure who commanded little real power; the de facto rulers of Japan were the lords of the Fujiwara clan. To enforce their power, the overcivilized court nobles had to rely on the warrior clans, samurai of lower birth but real fighting ability. The chief clans were the Heike (a.k.a. Taira) and the Genji (a.k.a. Minamoto).

“The Tale of the Heike” recounts the rise of the Taira to absolute power under the arrogant lord Kiyomori — and their fall in a revolt precipitated by his brutality and naked ambition. The war ended with the destruction of the Heike forces by the Genji in the sea battle of Dan-no-Ura in 1185.

Like “The Iliad,” “The Tale of the Heike” was originally sung. For centuries, blind musicians performed it, accompanying themselves on the biwa (Japanese lute). “Tale” is often compared to “The Song of Roland,” but it opens not with an account of imperial conquests in Spain — or an invocation of the wrath of a semi-divine hero — but with a reminder of the Buddhist belief in the transient nature of all things:

“The arrogant do not long endure:

They are like a dream one night in spring.

The bold and brave perish in the end:

They are as dust before the wind.”

In his elegant new translation, Royall Tyler divides the text into something resembling an opera libretto, with recitatives, arias and dialogue. This theatrical approach reminds the reader that “The Tale of the Heike” was intended to be heard, as well as read. The 14th century essayist Yoshida Kenko ascribed authorship to one Yukinaga, who worked with a blind musician, but numerous versions of the text exist.

“The Tale of the Heike” is not only an important historical document, but a work of great power and beauty. It’s easy to understand why its memorable scenes have inspired so many artists. Kiyomori ignores the oracular warnings that his arrogance will bring about his clan’s demise — even when the snowy forms in his garden transform into the skulls of men whose death he has ordered: “A mountain of skulls, now suddenly crammed with living eyes,/ all of them training on Lord Kiyomori an unblinking gaze.”

When it’s clear the Heike have been utterly defeated at Dan-no-Ura, the redoubtable Lady Nii takes her grandson, the child emperor Antoku, in her arms, telling him, “Down there, far beneath the waves,/ another capital awaits us,” and leaps into sea.

One of the great tales of Bushido, the samurai code of conduct, “The Tale of the Heike” overflows with accounts of battles, feats of derring-do, tender love affairs, descriptions of armor and heroes evoking their noble lineage as they challenge each other in duels. In places, “Tale” may remind Western readers of Sir Walter Scott — or Tolkien at his most fulsome.

For Americans, the characters’ names can seem as vexing as a Russian novel’s. The main Heike clansmen include Kiyomori; his father, Tadamori, his sons Shigemori, Motomori, Munemori and Tomomori; and his grandson Koremori. But the genealogies, notes and maps Tyler provides help sort things out. Readers willing to accept the challenges “The Tale of the Heike” offers will discover a moving story of exceptional strength and elegance.

The triumph of the Genji proved short-lived. Power struggles and civil strife continued to trouble Japan until 1600, when the Tokugawa established their Shogunate. Five hundred years after the conflicts recounted in “The Tale of the Heike” took place, the poet Basho visited one of the battlefields and evoked the same spirit of transience in the famous haiku: “Summer grasses/ All that remains of great soldiers’/ Imperial dreams.”

Solomon’s recent works include “The ‘Toy Story’ Films: An Animated Journey” and “The Art and Making of Peanuts Animation.’”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.