On Claire Messud and the importance of stories in a dying universe

Is meaning possible in a dying universe?

Over at Lit Hub on Wednesday morning, Claire Messud has a terrific essay on the importance of specifics as a way to keep ourselves contained.

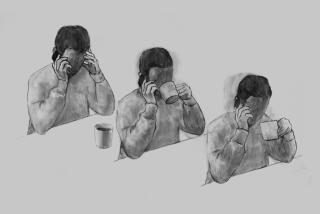

She begins by recalling “the feeling I had several times in youth, when lying in a field staring up at the night sky, that I might fall into the infinite void. For people like me, this idea mostly provokes anxiety. Oh, there’s wonder too, to be sure — how can one not marvel at our unlikely existence? — but this re-awakening to humanity’s insignificance re-awakens in me also my nine-year-old self, a child whose response to the magnitude of the universe might have been, ‘then I guess there’s no point going to school today. And maybe not much point getting out of bed, either.’”

Do I need to say that Messud gets it exactly right? Or perhaps it’s just that I know intimately the sensation she is describing, have known it since I was old enough to know anything at all. I remember once, at the age of 6, talking myself into an existential terror by trying to decide which was worse, death or the prospect of living forever, and finally deciding that each was equally intolerable.

This is the human conundrum, what E.L. Doctorow once described as “the philosophical despair of a mind in the appalled contemplation of itself.” It is the reason I have long tilted toward the existential, the necessity of, in Messud’s word, “dishes to be done, dogs to be walked, children to be bustled to their beds — the stuff of life, as we call it, when we don’t deem it the impedimenta to the life we might have lived.”

Here we see the appeal, the intent, of literature, which insists that in the smallest, most apparently negligible moments, our truest selves may be revealed. The idea, Messud explains, is that “in making up stories, as in reading stories, I could create a contained world in which an experience is shared in its entirety.”

For Messud, such a process begins at the level of the sentence, not only those we write but also those we carry within us, the lines by other writers that make us feel, as F. Scott Fitzgerald observed in the 1930s, that no one “has been so caught up and pounded and dazzled and astonished and beaten and broken and rescued and illuminated and rewarded and humbled in just that way ever before.”

Fitzgerald was referring to writing, but it’s not difficult to see this also through a reader’s lens. When we read, after all, we open ourselves to a kind of excavation, a process of revelation, in which we immerse ourselves in the world, the experience, of the other, and in so doing, enlarge our own.

In a constantly expanding cosmos — one where, as Messud unblinkingly reports, it is difficult not to “suspect that all of this — all the worlds, stars, galaxies and clusters in our observable universe — is but one tiny bubble in an infinite ocean of other universes” — it is easy to be overwhelmed by insignificance, by the realization that none of this matters, not a whit, that we are dead before we start.

Add to that the announcement this week from the Galaxy and Mass Assembly (GAMA) that our universe is “slowly dying” and it begs the question of whether meaning is possible at all.

I don’t know the answer — not on the cosmic level, anyway — although I suspect that it is not. And yet, the paradox is that this requires us to make, or find, our own meaning, our own small consolations, to live our lives not in the shadow of posterity but rather of the here and now.

“Fiction,” Messud writes, invoking Picasso, “is a means of ‘seizing power, of imposing form.’” Writing, in other words, offers a way of making meaning, even (or especially) if such meaning cannot last. Who are we? What are we doing here? The fact that it doesn’t matter is the reason it matters so much.

“These are the fragments I have shored against my ruins,” Messud insists, taking a line from T.S. Eliot. The implication is not that, in a dying universe, language can save us, but that, on the most essential level, it is the only thing we have.

twitter: @davidulin

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.