Scientist Converts Hunch Into Billion-Dollar Hope

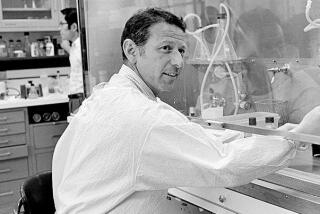

Fifteen years ago, Genentech Inc. hired Napoleone Ferrara, a young researcher from UC San Francisco, to work on relaxin, an experimental treatment to ease childbirth.

When he wasn’t busy with relaxin, Ferrara, an Italian-born gynecologist, pursued his pet project: a quest for the mysterious protein that causes blood vessels to grow.

As it turns out, relaxin was a failure in clinical trials. But Ferrara’s own project led to Avastin, an experimental cancer drug that Wall Street believes will become a $1-billion-a-year mega-hit for Genentech. Since the world’s second-largest biotech company announced last week that Avastin improved the survival rate of colon cancer patients, investors have added $11 billion to the company’s market value. On Thursday, Genentech’s stock closed at $60.14, down $2.73, on the New York Stock Exchange.

In biotechnology, as in Hollywood, a single blockbuster can change the fortunes of an entire company. Thanks to Ferrara’s efforts, Genentech may have that in Avastin, which could reach the market within a year if it wins Food and Drug Administration approval.

For Ferrara, 46, the successful colon cancer trials came after a long and frequently discouraging quest. Avastin hadn’t helped lung cancer or breast cancer patients, causing many investors to write off the drug.

“There is always so much apprehension about the result,” Ferrara said this week. “So much trepidation. We are very fortunate that it worked in these patients.”

But Ferrara said the trials’ findings only added to the mystery surrounding a protein to which he has devoted so much of his career. No one yet knows why Avastin works in some cancer patients and not in others. Also unanswered is why the drug eventually stops working in most patients who take it.

Ferrara thinks that there may be other proteins that spur blood vessel growth to tumors. “We have no proof that they exist, but I have reason to believe that they do exist, and we are trying to find them,” he said. “So there are still a lot of mysteries.”

A physician who prefers the laboratory to the clinic, Ferrara came to the U.S. in 1983 to study endocrinology after completing his residency at the University of Catania Medical School in Italy. He planned to return to his native country after a few years, but the research that led to Avastin altered those plans. He visits Italy frequently and was vacationing there when news broke about Avastin last week.

Ferrara first became interested in blood vessel proliferation at UC San Francisco. When his bosses at Genentech encouraged him to come up with a project, he leaped at the chance to continue his research.

As as a gynecologist, he understood that overgrown blood vessels could strangle ovaries and lead to infertility. He knew from studying medical literature that unchecked vessel growth, or angiogenesis, had been implicated in a host of diseases; years earlier, Judah Folkman of Children’s Hospital in Boston had observed that tumors couldn’t grow without a tangle of blood vessels feeding them.

In 1988, as a junior scientist at Genentech in South San Francisco, Ferrara had a hunch that he might find the protein he was looking for in the pituitary gland, the master switch at the base of the brain that controls growth and reproduction. He soon isolated a small amount of a protein that appeared to activate vessel growth. His next task was to determine the structure of the protein, the first step toward making a useful drug.

Proteins are made of amino acids, strung together like a necklace of colored beads. There are tens of thousands of different proteins in the body, each distinguished by the number and pattern of amino acid beads.

Ferrara had isolated a small piece of the protein structure when he asked Genentech protein chemist William J. Henzel for help in filling in the missing amino acid sequences. Intrigued, Henzel puzzled out the structure and fed the information into a database to find a match, just as police run fingerprints to identify a suspect.

It quickly became clear that Ferrara was on to something new -- the database produced no match. The memory of the moment leaves Ferrara stunned 14 years later.

He called the protein VEGF, for vascular endothelial growth factor, because it acted on the lining of blood vessels.

Back then, Arthur Levinson, now Genentech’s chief executive, was head of research, charged with overseeing the company’s 100 or so scientists. He spent a day a week reviewing early-stage projects, part of a weeding-out process that helped the company decide where to place its bets. Every three months, a committee of scientists evaluated advanced projects and decided which should go forward.

Ferrara’s project was high on Levinson’s list. The sales potential of VEGF was huge, because a drug that blocked the growth factor could starve tumors by shutting down the blood vessels that fed them. And the protein itself might be used to stimulate new vessels in patients with heart disease. (Genentech hasn’t had success in that area.)

“It showed a lot of promise,” Levinson said. “Napo was taking the company into a whole new area.”

By the end of 1989, Ferrara and a team of Genentech scientists had identified the gene that encoded the VEGF protein. But Monsanto scientists were fast on their heels; they too had found a version of VEGF. As so often happens in hot areas of science, a race was underway.

Ferrara, with the help from other Genentech scientists, worked hard to develop a first generation experimental drug to test in diseased mice. After being treated with the drug, the mice’s huge tumors stopped growing, and some animals lived for months.

The next hurdle: fine-tuning the drug so it would be suitable for humans. Ferrara teamed up with Leonard Presta, then Genentech’s guru of antibody drugs, to develop what ultimately became Avastin. Presta actually prepared two different antibodies: a large Y-shaped protein that became Avastin and a smaller protein shaped like a boomerang that Genentech is testing in patients with macular degeneration, a disease that causes blindness. Early human tests of that drug, called Lucentis, have been promising.

Genentech took an unusual approach in its clinical trials, testing the drug against many different cancers. Susan Desmond-Hellman, chief medical officer, said the company placed so many bets on Avastin because it was convinced the drug would work, though it didn’t know in which type of cancer.

The colon cancer patients received Avastin in combination with standard chemotherapy drugs, and in a high number of patients, it worked.

The company is releasing actual data from the clinical trial Sunday.

Ferrara said the results were good, but stressed that Avastin was not a miracle.

“We are not curing cancer. We think that is impossible for some time to come,” Ferrara said. “We hope this is a contribution in the right direction.”