Column: These ER doctors are rooming together to avoid taking coronavirus home to their families

They did their residencies together, they work in the same emergency room and they each recently started families.

And now these three doctors on the front lines of the pandemic have become even closer — though not in a way any of them really wanted.

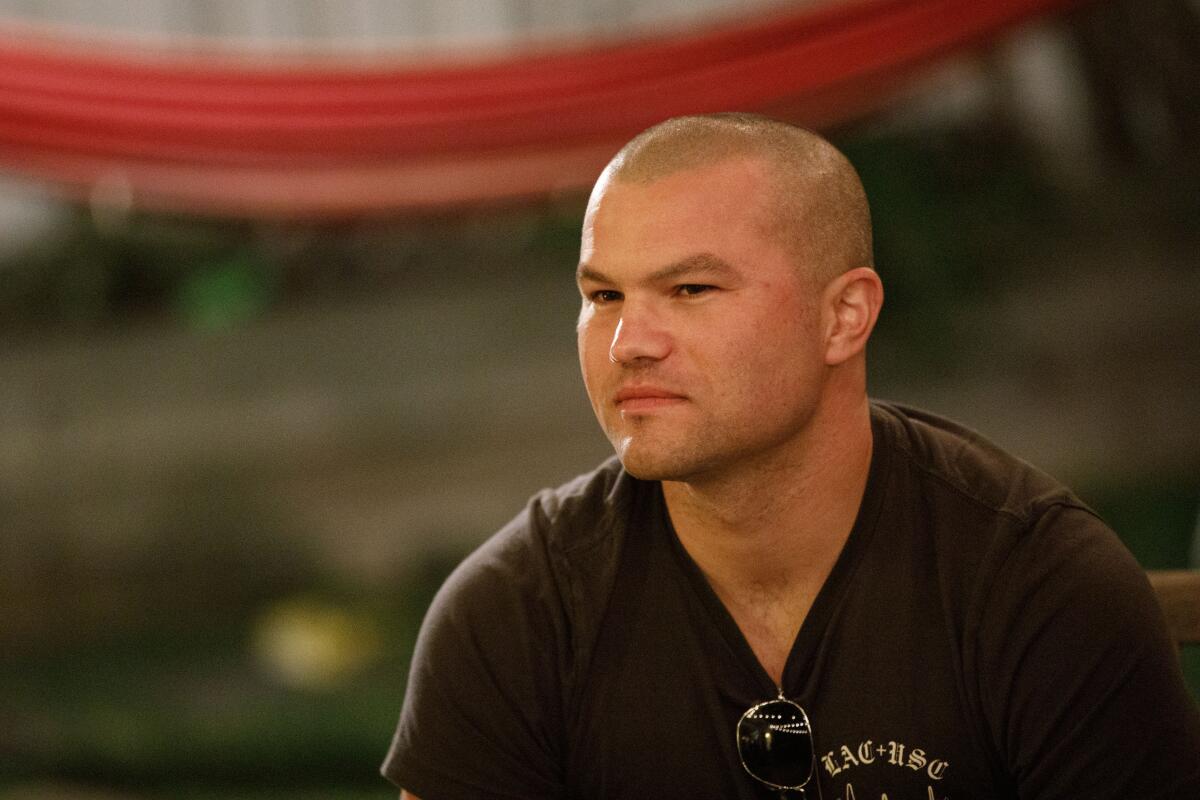

Andrew Herzik, Ben Musser and Craig Torres-Ness, who all treat coronavirus patients at Good Samaritan Hospital, recently became roommates, moving into temporary quarters together after deciding they didn’t want to risk exposing their wives and children to what they might bring home from the hospital.

“We all came to the same conclusion because we were coming into contact with the virus every day,” said Herzik. Even after scrubbing at the end of a shift, he told me, he didn’t feel comfortable being close to his wife and two kids, a 2 ½-year-old and an 11-month-old.

“We’d feel terrible if we got our wives and children sick,” said Musser, whose daughter is 10 weeks old.

“It’s pretty inevitable that it’s only a matter of time before we get sick — not if, but when,” said Torres-Ness, whose kids are almost 3 and 11 weeks. As the number of cases surges, he noted, medical professionals are at greater risk.

Rather than go home to their families after work, the doctors decided a week and a half ago to rent a three-bedroom Airbnb apartment not far from the hospital.

But that didn’t go so well.

“Oh my goodness, it was a disaster,” said Musser, explaining that the walls were thin and the family next door was loud. “You could hear every footstep and you could even hear the refrigerator door open. ... At 2 a.m., all you heard was loud bass.”

Musser and Torres-Ness each survived one night in the apartment after grueling ER shifts, but they couldn’t get the rest they needed. They gave a heads up to Herzik, and Plan B was hatched.

Herzik grew up in Redondo Beach, where he still serves as a lifeguard — the job that made him want to be a doctor. He and his wife, Alyson Bourne, now live several minutes away from his parents, also in Redondo.

The solution seemed obvious to one and all.

Herzik’s parents, Terry and Deborah, agreed to pack up quickly and move out of their house and into their son’s home along with Alyson and the two kids. That cleared the way for Andrew and his two doctor pals to move into his childhood home.

“My parents were like, super-game,” said Herzik.

Herzik’s father is a commercial sea urchin diver and his mother is a nurse practitioner at El Camino College, where she had concerns about her own exposure to the virus. But Deborah Herzik has been working from home of late, practicing telemedicine, so moving into Andrew’s home seemed safe enough.

“So now they have a nice comfy home to live in and we get to be here to help Aly and be with our grandchildren,” said Deborah.

About every other day, depending on his ER schedule, Andrew Herzik meets his wife for a walk or to have dinner. The routine is for him to wait until his kids are asleep, then walk around to the backyard of his home. He sits on the patio while Alyson and his parents stay a good 10 feet or so away.

“Gus would want to run into his arms if he saw Andrew,” Alyson said of their 2-year-old son, who has asthma, a condition that makes them extra leery of exposure.

On Monday night, all three doctors gathered in the backyard while Herzik’s parents and wife made pasta Bolognese, with broccoli, and set the food on a patio table for the doctors to retrieve.

They may be working in a medical war zone, the doctors said, but they didn’t feel deserving of much sympathy on this particular night. Being served a gourmet dinner in a nice backyard near the beach didn’t seem like all that much of a sacrifice, Musser and Torres-Ness said.

“I’m 35 years old and having a slumber party with my buddies,” said Torres-Ness.

But being without their families, and dealing with the growing crush of patients and the uncertainty of how bad things will get, is more than a little stressful, and they know it is stressful for their wives to manage without them, too. Musser visits his home in Montrose when he can for safe-distance visits, Torres-Ness does the same in Los Feliz, and there are lots of phone calls and Facetime connections.

“I sit in my backyard and it’s like a prisoner having a visit,” said Musser. “Stay six feet away, and no touching.”

Torres-Ness said he slept on the living room sofa in his two-bedroom apartment until that felt unsafe because of the tide of patients coming through ER with virus symptoms. He’s seeing as many as 10 such cases daily, and to conserve equipment in anticipation of a possible surge, he and his colleagues are often re-using the same protective gear for extended periods.

Even routine emergencies are problematic now, he said. Because patients can be asymptomatic, the entire medical team has to be protected against the virus even to treat someone with an injury or a heart problem. And yet despite the growing risk, Torres-Ness said, he postponed a scheduled paternity leave to serve during the crisis.

“This is what we trained for,” he said. “To be able to respond to whatever the situation is.”

All three doctors are employed by USC’s Keck School of Medicine, which provides emergency services at Good Sam, Verdugo Hills Hospital, L.A. County-USC Medical Center and the Keck Medical Center. Dr. Carl Chudnofsky directs all of Keck’s ER services and called Herzik, Musser and Torres-Ness “three really good young doctors.”

In the time since the trio made their own housing arrangement, Chudnofsky said, Keck has begun providing hotel rooms and apartment units for other employees.

“This involves two types of housing, one for those who have been exposed and need to self-quarantine, and we’re also offering housing for front-line caregivers who don’t want to go home because of living with an elderly person or a sick person or because they’ve got a new baby,” Chudnofsky said.

Of those quarantined, Chudnofsky said, no one has tested positive. But ER patient volume ticked up on Monday, and it surged again Tuesday, so Chudnofsky is planning for the possibility of greater demands on his staff. He said he’s pulling his own ER shifts, too, and is working 10 to 12 hours a day, seven days a week.

“Hopefully we’ll get through this relatively unscathed,” he said, adding that Keck is also making mental health counseling and other supportive services available to employees who need them..

As for the three doctors, they said they tried to get a refund after moving out of the apartment they rented, but so far no luck. If they get stiffed, maybe the apartment can be one of the housing options for their colleagues, Torres-Ness said, if the party house next door turns down the volume.

That doesn’t sound like too much to ask, given the compromises so many medical pros are making these days.

“My wife sent me a video yesterday of our 11-month-old, walking for the first time,” Herzik said with a combination of pride and regret.

This is a time when all of us are learning to sacrifice and adapt, to be together and to be apart, and to be grateful to those who stand ready to serve.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.