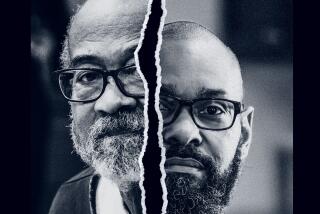

Book review: ‘The Man in the Rockefeller Suit’ by Mark Seal

Great con artists understand this about human nature: The suckers want to be taken.

In 1978, a poor, semi-educated German teenager named Christian K. Gerhartsreiter arrived in New England on a falsified student visa. Brilliant, charismatic and twisted, he soon realized that Americans were easily duped by claims of great wealth and European titles.

Cultivating an eccentric, Segway-riding persona, a wardrobe from “The Official Preppy Handbook” and a posh accent, Gerhartsreiter honed his deceptions from San Marino’s leafy streets to Greenwich, Conn., to Wall Street, assuming roles of British baronet, Hollywood producer, Ivy League graduate and high-flying bond trader. But it was on Boston’s tony Beacon Hill that he settled into the biggest con of his 30-year career, as the fictional Clark Rockefeller — a cousin of the billionaire clan.

As Mark Seal recounts in his impeccably reported and fascinating book “The Man in the Rockefeller Suit,” Gerhartsreiter’s strategy was disarmingly simple. He joined congregations where affluent bluebloods worshiped and ingratiated himself at church mixers — wealthy widows were great stepping stones.

After squeezing his new friends for money, housing and social connections, he’d move on, shedding personas like rattlesnake skin, leaving mystified, angry and — in San Marino at least — missing people in his wake.

Right before Seal’s book went to press, authorities charged Gerhartsreiter with the murder of Jonathan Sohus, who disappeared with his wife, Linda, in 1985 under suspicious circumstances from the San Marino property where Gerhartsreiter, calling himself Christopher Chichester, lived in a small guesthouse. Jonathan Sohus’ skeleton was found buried on the property in 1994 when new owners put in a pool. Luminol tests showed copious amounts of blood had been spilled on the guesthouse floor, and a man calling himself Christopher Crowe popped up in Connecticut, trying to sell the couple’s truck. Gerhartsreiter, who maintains his innocence, is being extradited to Los Angeles to stand trial for Jonathan Sohus’ murder. Sohus’ wife’s fate remains unknown.

The compulsive charlatan might still be impersonating a Rockefeller, bullying his wealthy ex-wife, swanning around private clubs and rocking his horn-rims, Topsiders and impressive but fake art collection to all his Beacon Hill neighbors if not for one mistake.

After a bitter 2007 divorce left him with few visitation rights, Gerhartsreiter kidnapped his daughter “Snooks” and disappeared. When the FBI arrested him in Baltimore, the long con finally unraveled. In 2009, he was convicted of kidnapping and sentenced to four to five years in prison, buying the L.A. investigators time to put together the murder case with “additional evidence gathered using modern technology,” according to The Los Angeles Times.

Seal’s book reads like a true-life “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” a cautionary tale about how people smarter, richer, better educated and more worldly than you and me were taken in by this emperor with no clothes. Several times, I put it down in disbelief. How could he have fooled so many people — including his high-powered, Harvard MBA-holding wife — for so long?

Seal, who first tumbled down the Gerhartsreiter rabbit hole when profiling him for Vanity Fair, shows how the imposter used his computer skills, personal magnetism, pedigree dog and even his cherubic daughter to worm his way into elite circles. Like many con men, Gerhartsreiter had a preternatural ability to suss out individuals susceptible to his fabrications, who would then vouch for him and open doors.

But as Seal points out, even in pre-Google times, basic library research would have revealed that Gerhartsreiter wasn’t the 13th Baronet of Chichester, grandson of Lord Mountbatten, owner of England’s Chichester Cathedral, producer of “Alfred Hitchcock Presents,” a Yale/Harvard grad or owner of the Mondrians, Rothkos and Motherwells on his walls.

When questioned, Gerhartsreiter’s friends resort to mental jujitsu to explain his mesmeric sway.

Architect Patrick Hickox, one of the brave souls who spoke to Seal on the record, used Truman Capote’s phrase “a genuine fraud.”

Hickox saw his friend “Clark” as “a person who actually may be genuine, but built upon a fictional armature” and an “archetypal immigrant, who constructs a new life and a new persona, free of the constraints of the country he left behind.”

Others describe their awe at being entertained by “Mr. Rockefeller” at the Harvard and Algonquin clubs. How did he breach these citadels? Private clubs often had reciprocal membership with lesser clubs, and author Seal himself cleverly gate crashes the Algonquin by announcing he belongs to “The Aspen Club” — the name of his gym.

While Gerhartsreiter perfected the role of wealthy bon vivant, fatal flaws seethed below the surface. (One expert witness testified he met all the criteria for delusional disorder, grandiose-type insanity).

With his charm, social standing, jobs and wife’s money, Gerhartsreiter could easily have made a real life for himself instead of existing as a simulacrum. But he was too hollow inside.

When the Rockefeller mirror finally cracked, his deception — and an alleged murder — were laid bare.

And so were some inconvenient truths about human nature.

Denise Hamilton’s new crime novel, “Damage Control,” will be published by Scribner in September.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.