Boiling Point: After decades of abuse, oceans could offer a climate change solution

We’re less than a week away from a presidential election that could shape the planet’s climate for decades or even centuries to come. So let’s talk about a (seemingly) unrelated story: dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane.

Use of the pesticide, better known as DDT, was banned in the U.S. in 1972, after marine biologist Rachel Carson awakened the nation to its toxic and long-term consequences in her book “Silent Spring” and ignited an environmental movement.

If you’re anything like me, you probably haven’t spent too much time thinking about DDT. I was born 20 years after it was banned and basically thought it was a problem of the past.

So I was startled by my colleague Rosanna Xia’s latest investigation, “How the waters off Catalina became a DDT dumping ground.” Rosanna, an environment reporter who covers the coast for The Times, discovered that as many as half a million barrels of DDT-laced sludge were dumped into the ocean off the coast of Los Angeles from 1947 through 1961. Many of the barrels were punctured so they would sink more easily, possibly allowing chemicals to leak on the way to the sea floor.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

DDT can take generations to break down, so it’s still part of our ecosystems and food chains. It’s in dolphin blubber and continues to show up in fish commonly caught off local piers. It’s in our bodies, possibly interfering with our immune systems or increasing breast cancer risk, although the health impacts are still being studied. It’s passed on from mothers to their daughters.

And any time we’re talking about abusing our oceans, there is indeed a climate change connection.

I got on the phone with Rosanna to ask some questions about her remarkable reporting, including what it means for the choices we face now as a society. Here are some highlights from our conversation, edited and condensed for clarity.

ME: How did you find out about these barrels getting dumped in the ocean?

ROSANNA: I’m grateful for researchers who follow our work at the L.A. Times. David Valentine, the scientist in the opening of the story, reached out and said, “Hey, we have been working on this, I’m not really sure what to do with this information.” And we talked for a bit. I quoted him saying, “Holy crap,” in the story, but I definitely also thought, “Holy crap,” the first time we spoke.

Especially if you grew up in Los Angeles or were around in the 80s and 90s, you may have known about the sewage dumping and the Superfund battle — the public outcry then was very loud on the Palos Verdes shore. But I don’t think many folks knew about the deep-sea offshore dumping closer to Catalina Island. Going through the records and finding the small circle of scientists who did know about this, it was an incredible mystery that kept unraveling.

ME: Actually, I didn’t even know about the more well-known history of the Superfund site near Palos Verdes. So it wasn’t just the dumping of barrels near Catalina that was mind-boggling to me.

ROSANNA: I’m glad you said that. I think this story was important for informing a new generation of Californians who might not have known the original history of DDT, or weren’t aware that the nation’s largest DDT maker was right here in L.A.

ME: DDT was banned nearly 50 years ago, but it’s still here. And we’re still producing huge amounts of “forever chemicals” that often end up in the ocean. Why is it so difficult for society to learn that the ocean can’t be its dumping ground?

ROSANNA: When I was going through the news archives, newspapers kind of stopped writing about DDT. And when we stopped writing about DDT, people stopped thinking about it. And when people stopped thinking about it, the funding for scientists went in a different direction.

One scientist told me: “Microplastics and PFAS are the new DDT.” That’s what everyone wants answers for, so that’s where all the research is going. But we need to remember that DDT isn’t gone. It’s still an issue.

PFAS, microplastics, BPA — I’m not dismissing those problems. They all pose major concerns and are toxics we should be talking about. But the thing with DDT is we still haven’t quite figured out how it affects us in the long term.

ME: Do all those DDT barrels pose risks to people who are swimming, surfing or snorkeling off the coast?

ROSANNA: I really tried to answer that question. And there’s no clear answer. The barrels are 3,000 feet deep. It’s a very low-oxygen environment, and there are a lot of unanswered questions of how much the chemical is moving up the water column. There’s some deep-water upwelling that happens in that area. But we won’t know until we have further studies.

But on the Palos Verdes shelf where the Superfund site is, anglers are still warned not to catch certain fish because of the DDT dump from the sewage outfall from decades ago.

ME: We should talk about climate change. By continuing to burn fossil fuels, we’re once again changing our oceans in ways that will reverberate for decades or centuries. There’s a connection here, right?

ROSANNA: We can’t solve the problems of our future without fully understanding the past. We see so much discussion right now about the ocean as a solution to so many of our problems as the climate continues to warm, whether it’s counting on the ocean to absorb our heat and carbon dioxide, or deep-sea mining for resources, or providing more sustainable food for the world.

But how can we even think through these solutions without learning the lessons from our past and understanding how much we have already harmed the oceans?

ME: Well, how can we think through that? What lessons did you take from reporting this story?

ROSANNA: I think the story shines a light on the need for environmental regulation. This ocean dumping back in the 1950s was technically legal. Mankind allowed this to happen, and now this disregard for nature is coming back to haunt us. So what are we allowing to happen today that will haunt our kids and grandkids decades from now?

More than half the Earth’s oxygen comes from the ocean. That statistic always floors me. And the sea itself covers more than 70% of our planet, and it has absorbed more than a quarter of the carbon dioxide released by us since the industrial revolution, and about 90% of the resulting heat. And so the ocean really is both a victim and an unsung hero of climate change.

I often hear scientists talk about ocean acidification as “the other carbon dioxide problem.” So we do historically turn to the ocean as this seemingly unlimited sink that just absorbs everything.

ME: Are there ways to solve that problem other than just reducing carbon emissions?

ROSANNA: I remember a friend feeling really emotional when the Amazon was burning. She said, “The Amazon is the lungs of our planet.” And I said, “The oceans are the lungs of our planet too.” We sometimes overlook the ocean — the kelp forests that produce so much oxygen, and the carbon sequestration in our wetlands that have been paved over.

A really cool, robust conversation has been gaining momentum of looking at the ocean as not just a victim of climate change, but also a solution. And we need to understand what we’ve already done to the ocean before we turn to it for solutions.

***

Again, here’s the link to Rosanna’s story. And here’s what else is happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

It’s been five years since the Aliso Canyon gas leak spewed record-breaking amounts of methane into the atmosphere and forced thousands of people to evacuate. This week the Los Angeles Daily News published an excellent series tracking the fallout, including stories on the nearly 36,000 plaintiffs who still have pending lawsuits against Southern California Gas; the long-term health study of Porter Ranch residents that is just now getting underway; the rapid recovery of the neighborhood’s real estate market, even as some residents continue to worry; and the debate over whether Aliso Canyon is still needed for energy reliability.

California’s cleanup of lead contamination from the Exide battery facility is behind schedule and over budget. For all the criticism Exide has taken for polluting communities in southeast L.A. County, regulators haven’t done a great job either. That’s the conclusion of a state audit that blames poor management at the Department of Toxic Substances Control for a failure to remove lead-tainted soil more quickly from facilities including child-care centers, schools and parks, The Times’ Tony Barboza reports.

Remember “Exxon Knew”? Well, turns out General Motors and Ford knew too. Maxine Joselow reports for E&E News that scientists working at the two U.S. automakers did research as early as the 1960s showing that tailpipe emissions from cars were contributing to climate change. But like Exxon, the companies worked for decades to obscure the science and block climate action.

CALIFORNIA BURNING

Even after months of devastating and deadly blazes, fire season is far from over. Firefighters were making progress battling two wind-driven fires in Orange County, but only after nearly 100,000 people were forced to evacuate. Southern California Edison says its power lines may have ignited one of those conflagrations, even as Edison (along with Pacific Gas & Electric and San Diego Gas & Electric) shut off power to some customers to try to prevent ignitions. Southern Californians found themselves breathing the nation’s worst air as new and existing fires burned, with powerful Santa Ana winds sending ash and smoke across the region.

Many Californians face the choice of leaving the places they love or sticking around and trying to stay safe amid growing fire danger. My colleague Joe Mozingo talked with people who moved to the woods for a serene lifestyle to find out how they’re feeling. In Butte County, residents knew the next Paradise could be coming but watched in frustration as officials failed to get urgently needed forest projects done quickly, as Joseph Serna reports. And lest we think this is only happening in California, the Denver Post’s Bruce Finley reports that Colorado is experiencing many of the same symptoms of the climate crisis as we are.

Kim Abeles uses smoke and smog to create art highlighting air pollution and fires. For years, Abeles has placed stenciled plates or fabrics on a Pasadena rooftop to collect smog raining down from the sky, with stencil designs ranging from presidents’ faces to catalytic converters. Now she’s using falling smoke and ash from fires to create images of the deck chairs on the Titanic, as my colleague Laura Zornosa reports. Personally, I think this a fascinating way to draw attention to environmental calamity.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to The Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most, and makes newsletters like Boiling Point possible. Become a Los Angeles Times subscriber.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

When Joe Biden talks about phasing out oil, does it help or hurt with swing-state voters? Polling suggests Biden’s comment during the second presidential debate — that he would “transition from the oil industry” — isn’t the liability President Trump has made it out to be, per my colleagues Evan Halper and Noah Bierman. In California, meanwhile, activists, the oil industry and organized labor are drawing battle lines following Gov. Gavin Newsom’s call to ban fracking, as KQED’s Ted Goldberg reports.

More striking than Biden’s comment on phasing out oil, at least to my mind, was the discussion of health risks to people of color living near polluting facilities. Rather than deny the existence of environmental injustice, Trump suggested that people of color will be fine because “they’re making a tremendous amount of money.” Biden responded: “Those front-line communities, it doesn’t matter what you’re paying them, it’s how you keep them safe.” More details here from the Washington Post.

Major companies have made a big deal the last few years about their plans to reduce planet-warming emissions. But in an important data analysis, Bloomberg reports that “the biggest U.S. companies — even those with ambitious green agendas — are throwing their support behind lawmakers who routinely stall climate legislation,” giving far more money to those lawmakers than to supporters of climate action. That description applies to companies including General Electric, Google and Microsoft.

ALL ABOUT CLEAN ENERGY

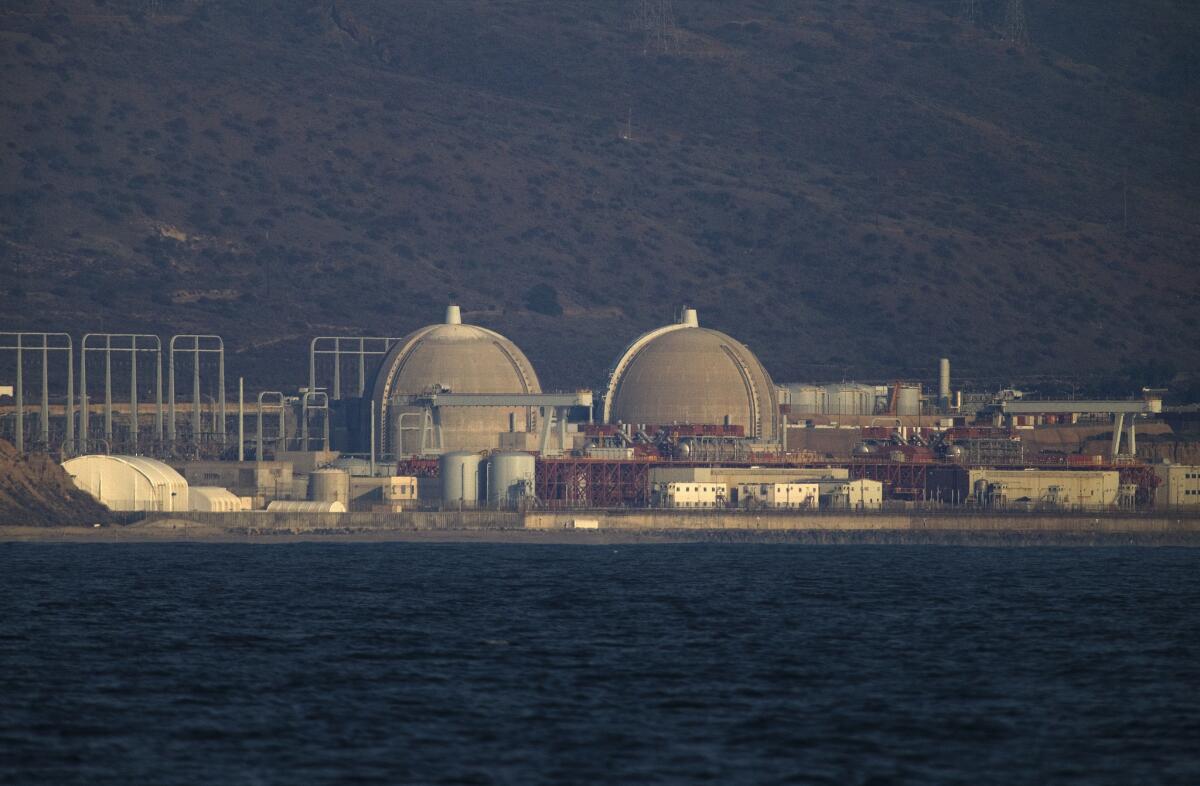

The federal government approved designs for the first small nuclear reactors, to be built in Idaho. Supporters hope the technology can offer a less controversial path forward for nuclear power, but lots of uncertainty remains, Jonathan Moens reports for InsideClimate News. In Southern California, meanwhile, the long process of dismantling the San Onofre nuclear plant continues, with the domes along Interstate 5 expected to start coming down in 2025, per the San Diego Union-Tribune’s Rob Nikolewski. Along the Central Coast, California’s last operating nuclear plant keeps going offline due to mechanical issues.

Tesla earned its fifth quarterly profit in a row. The company is making more money than ever, with one analyst telling The Times’ Russ Mitchell that the electric vehicle company “will become a fairly mainstream automaker before the midpoint of this decade” if it stays on this path. At the same time, some Tesla cars continue to experience problems, with Russ reporting that the company was ordered to recall 30,000 vehicles in China after complaints about a potentially dangerous suspension issue.

How about one more Trump administration story before the election? Peter Fairley reports for InvestigateWest that political appointees at the Department of Energy have buried or blocked dozens of clean energy studies with findings inconvenient to the fossil fuel industry. These studies have been funded by taxpayers and are sometimes mandated by Congress.

What do you want to know?

When you think about California’s climate future, what comes to mind? What keeps you up at night, and what gives you hope or gets you excited? What do you want to understand, and what should I?

This newsletter is for you, to help you understand how we’re changing our world and what we can do about it, and I want to hear your questions, concerns and ideas. Email me or find me on Twitter.

ONE MORE THING

When I worked for the Desert Sun in Palm Springs, I wrote an investigative story digging into the enormous influence exerted by a farmer in California’s Imperial Valley, Mike Abatti, over the largest share of Colorado River water in the West. One of my findings was that L. Brooks Anderholt — an Imperial County judge who made a consequential ruling in Abatti’s favor — had a long history of business and social ties to several members of the Abatti family.

Anderholt never agreed to talk with me. But two years later, a major component of his ruling has been overturned on appeal, and now the Imperial Irrigation District — the counterparty in Abatti’s lawsuit — is asking the appellate court to block Anderholt from adjudicating the remainder of the case. The district’s attorneys have cited my reporting as evidence that Anderholt is biased.

Will the judge now be compelled to respond to questions I raised in 2018? That’s yet to be seen. But I’ll be watching closely, in the hopes of finally getting some answers. As TV character Irina Derevko once said: “Truth takes time.”

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.