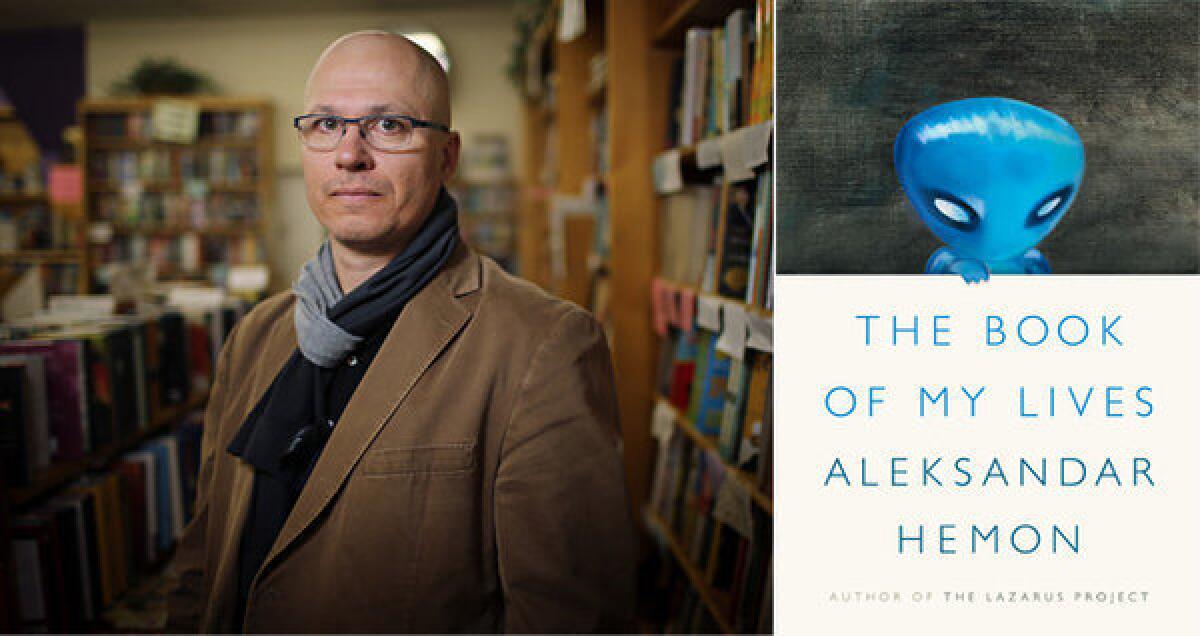

‘The Book of My Lives’ offers fragments of a writer’s life

There’s a tendency to look askance at essay collections, to see them as somehow incidental, as if they had no urgency of their own. I defy anyone to make such an argument after reading Aleksandar Hemon’s “The Book of My Lives.”

In his first book of nonfiction, Hemon takes what might otherwise seem a group of random pieces and arranges them so they are more than the sum of their parts. On the one hand (let’s be honest), that’s a bit of a contrivance, since these essays were all written at different times for different venues. But the trick of the book is how Hemon makes them add up to something — if not a life, exactly, then a life in collage.

“[I]n my books, fictional characters allowed me to understand what was hard for me to understand (which, so far, has been nearly everything),” Hemon writes in “The Aquarium,” describing a breakfast table epiphany brought on by a conversation with his eldest child, 3-year-old Ella. “Much like Ella, I’d found myself with an excess of words, the wealth of which far exceeded the pathetic limits of my biography. I’d needed more narrative space to extend myself into; I’d needed more lives.”

“The Aquarium” is the closing essay in “The Book of My Lives,” and it’s a killer, in more ways than one. Originally published in 2011 in the New Yorker, it details, in language sharp as a scalpel, the death of Hemon’s 1-year-old daughter Isabel from a rare cancer of the brain. “And now my memory collapses,” he writes of the moment when rationality deserts him: “our beautiful, ever-smiling daughter, her body bloated with liquid and beaten by compressions,” lying dead on a table in the ICU.

That ruthless unwillingness to look away has long been a hallmark of Hemon’s writing. Born in 1964 in Sarajevo, he relocated to Chicago after being stranded there as a visitor at the start of the Bosnian war. His previous work — two novels, including “Nowhere Man” and the National Book Award-nominated “The Lazarus Project,” and two story collections, “The Question of Bruno” and “Love and Obstacles” — has explored issues of history and identity, often using his experience as a catalyst.

Something of a similar focus emerges in “The Book of My Lives,” which takes us through 15 essays, 15 sets of incidents that echo back and forth like related episodes.

This intention is clear from the shape of the collection, which begins with an account of the birth of Hemon’s sister, Kristina, in 1969, and his attempt, as a 4-year-old, “to exterminate her as soon as an opportunity presented itself.” On its own, such a revelation is, by turns, horrifying and utterly familiar (especially to anyone with a younger sibling). Yet read in balance with “The Aquarium,” it takes on a different meaning, as a mirror or a frame.

When Hemon writes of his sister’s birth, that “nothing has ever been — nor will it ever be — the way it used to be,” he is also talking about his daughter, who haunts these pages like a hidden ghost. And when he observes that “I was terrified with the possibility of losing her … although I knew how I could end her life, I didn’t know how I could stop her from dying,” he is establishing the essential friction of the collection, which, for want of a better phrase, let’s call the friction between inner and outer life.

That such a tension is also the defining tension of the writer does not escape Hemon’s notice, for among his purposes is to offer up a kind of author’s autobiography. Not in regard to his publishing history or literary gossip (both of which he blessedly overlooks), but more in terms of sensibility.

“It was better to be silent,” he admonishes, “than to say what didn’t matter. One had to protect from the onslaught of wasted words the silent place deep inside oneself, where all the pieces could be arranged in a logical manner … where even if you ran out of possibilities, there might be a way to turn defeat into victory.” This is as good a description as I’ve read about what it means to sit down and write — not least because it also reflects Hemon’s experience of exile.

“Nowadays in Sarajevo, death is all too easy to imagine and is continuously, undeniably present, but back then the city — a beautiful, immortal thing, an indestructible republic of urban spirit — was fully alive both inside and outside me,” he writes in “The Lives of a Flaneur,” describing what he left to come to Chicago, a city he has had to learn to see “through the eyes of Sarajevo,” creating “a complicated internal landscape in which stories could be generated.”

Of course, Chicago is also where Hemon met his wife, who, as the editor of a book about Chicago, commissioned one of these essays (the delightful “Reasons Why I Do Not Wish to Leave Chicago: An Incomplete, Random List”) — a link that brings us back to Isabel. That’s the sneaky power of “The Book of My Lives,” that its pieces talk to one another like filaments of memory.

Not everything is of equal intensity; “Sound and Vision” is a slight account of a vacation gone awry, while “The Kauders Case” never fully reckons with its precipitating incident, a Sarajevo birthday party with an ironic Nazi theme. Still, when Hemon frames the event as “a performance, a bad joke at worst,” we believe him, not least because of what comes afterward.

Part of what Hemon is tracing is his own awakening, his discovery that what we say and do matters, that there are consequences for everything. It’s no coincidence that what passes for a title essay here involves a former professor of his who became an apologist for Bosnian Serb strongman Radovan Karad¿i¿.

This may be the teacher who introduced Hemon to Montaigne, but his most essential lesson is that literature does not exist in a vacuum, that what we read and write is a reflection, in the deepest sense, of who we are.

That, in turn, reiterates the message of this collection: the necessity of engaging, of standing up, of seeing one’s life in more connective terms. “I excised and exterminated that precious, youthful part of me,” Hemon writes, “that had believed you could retreat from history and hide from evil in the comforts of art.”

The Book of My Lives

Aleksandar Hemon

Farrar, Straus & Giroux: 214 pp., $25

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.