Why Kafka Matters

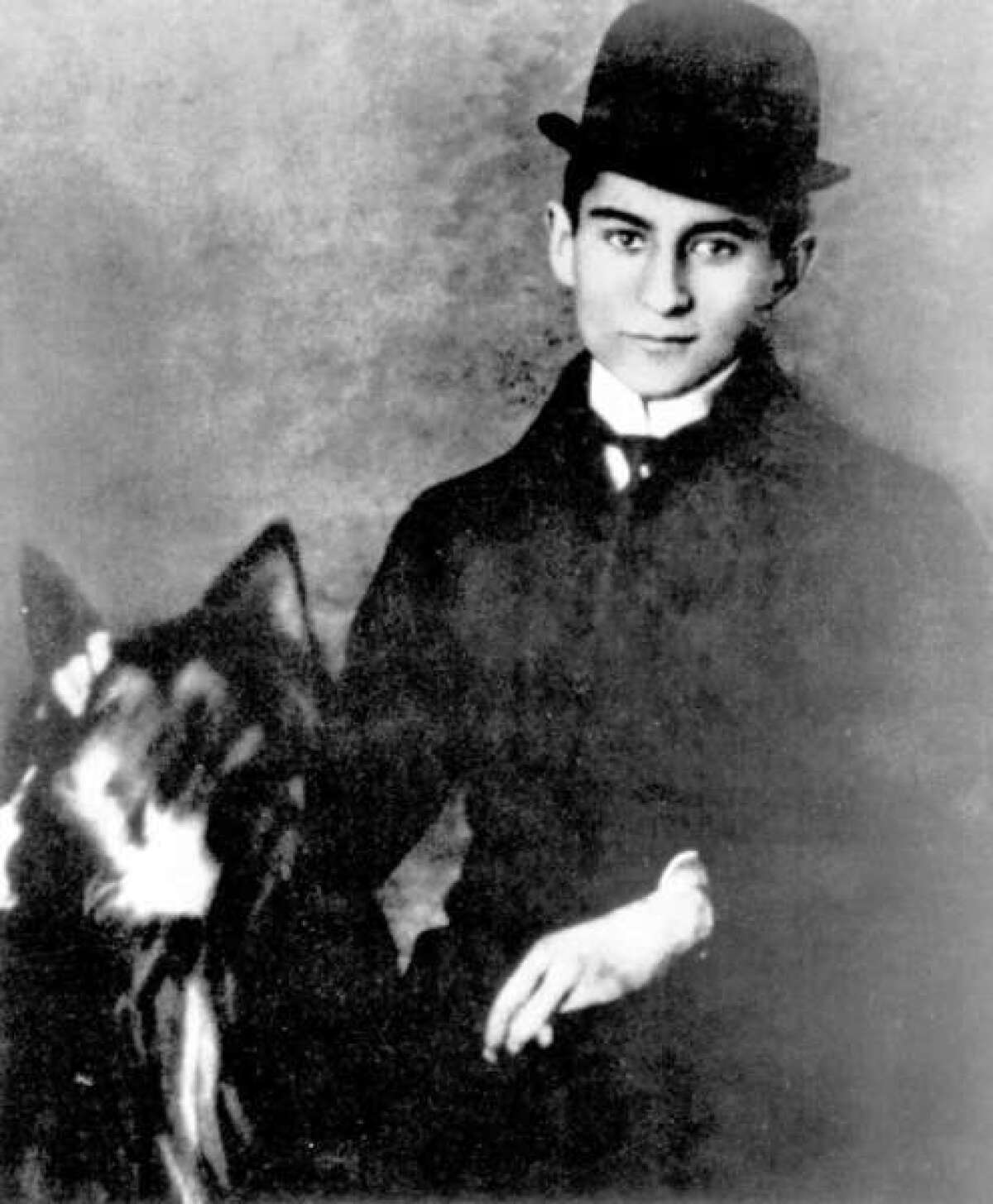

In the July/August issue of the Atlantic, Joseph Epstein uses the release of Saul Friedlander’s book “Franz Kafka: The Poet of Shame and Guilt” to pose the larger question of whether Kafka is still relevant.

“Great writers are impressed by the mysteries of life; poor Franz Kafka was crushed by them,” he observes, noting that “Kafka’s small body of work, which includes three uncompleted novels, some two dozen substantial short stories, an assemblage of parables and fragment-like shorter works, diaries, collections of letters (many to lovers whom he never married), and the famous ‘Letter to His Father,’” represents an achievement so insular that it “cannot be either explained or judged in the same way as other literary artists.” What this means, Epstein goes on, is that, in Kafka’s universe, “illogic becomes plausible, guilt goes unexplained, and brutal punishment is doled out for no known offense.”

Let me offer a dissenting view: The guilt and punishment in Kafka’s writing are so pervasive because they are often that way in contemporary life. Kafka understood this, just as he understood that none of us, regardless of intentions, are ever wholly innocent. Just look at “The Trial”’s Josef K., both victim and collaborator, or poor Gregor Samsa, who, as “The Metamorphosis” begins, “awoke one morning from uneasy dreams” to find himself “transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.”

I love “The Metamorphosis”; it’s one of my favorite works of literature, because of the way Kafka personalizes the alienation, making Gregor complicit in his fate. He becomes an insect, after all, because he is already an insect, scurrying from train to train, town to town, supporting a family that takes advantage of him, as we see once he is afflicted and they must care for themselves. Gregor’s disaffection is, in some sense, the disaffection of anyone who has ever been in his position — unthanked, taken advantage of, overworked — and yet, it is also his fault.

For me, this is the key lesson of Kafka’s writing, that we are all responsible for our own fates. It’s a starkly existential position that is also a quintessentially modern point-of-view.

Epstein makes a lot out of the narrowness of Kafka’s writing, suggesting that his work adds up to little more than “the sad story of a lost soul destroyed by modern life.” I agree that his books are highly autobiographical (if by autobiographical, we mean that they trace the parameters of the writer’s inner life), but the miracle of them is that they manage to reach out, somehow, to connect to our isolation, to reflect emotions that emerge in all of us.

“My conception of a novel is that it ought to be a personal struggle, a direct and total engagement with the author’s story of his or her own life,” Jonathan Franzen notes in his essay “On Autobiographical Fiction.” “This conception I take from Kafka, who, although he was never transformed into an insect, and although he never had a piece of food (an apple from his family’s table!) lodged in his flesh and rotting there, devoted his whole life as a writer to describing his personal struggle with his family, with women, with moral law, with his Jewish heritage, with his Unconscious, with his sense of guilt, and with the modern world.”

Franzen gets it just right, the heart of Kafka’s project, which is to interpose that inner landscape on the outer world. Much has been made of the opening of his novel “Amerika” (or “The Missing Person”), in which a young man named Karl Rossmann arrives in New York harbor and sees the Statue of Liberty, its “arm with the sword now reached aloft.”

What do we make of such an image? Over the years, it’s been explained as a mistake (Kafka wrote about America without ever having been here) or a clue that we have entered the territory of a dream. For me, however, it’s more concrete and universal — a metaphor for Karl’s disassociation; in Kafka’s universe, even the land of opportunity comes armed with a sword.

There’s no doubt this can make for heavy sledding; Kafka is not, as Epstein argues, always (or even often) fun to read. But that suggests a misapprehension about why we read, or at least why I do; I’m not looking to be entertained. I think Epstein misses the boat on Kafka’s humor, which is subtle, pointed: There’s something bitterly comic about Josef K.’s never-ending slog through the legal bureaucracy, as there is about a man who wakes up as a bug.

More to the point, Epstein seems to expect some sort of logical explanation for a universe that is by its nature devoid of logic, which is how Kafka saw the world. “For a man who claimed to be under the lash of a tyrannical father,” he writes, “Kafka nevertheless lived at home until he was 31. He insisted that his job stifled him, yet he never left it until compelled to by illness. He strung women along — poor Felice Bauer, twice his fiancée over the course of several years — holding out promises of marriage on which he did not deliver.”

That this is true is beside the point, at least when it comes to Kafka’s work. His inability to get out from under his father, or his job, to deliver on his promises, is part of what makes him human, part of the enigma of his self. This, in turn, is what his writing reflects.

We are all of us conflicted, all of us trapped in situations we can’t escape, even (or especially) if others think we can. And Kafka remains our greatest chronicler of this ambivalence precisely because he understood it — and the way modernity offers little opportunity for it to be resolved.

ALSO:

Twitter and the life of the mind

Watch the first trailer for ‘Salinger,’ the movie

Rebecca Solnit’s ‘The Faraway Nearby’ offers a storyteller’s empathy

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.