Tasting Notes: ‘Vibration Cooking’ is still prescient at 50

“And when I cook, I never measure or weigh anything. I cook by vibration. I can tell by the look and smell of it. Most of the ingredients in this book are approximate. … Different strokes for different folks. Do your thing your way.”

By the second paragraph of “Vibration Cooking, or the Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl,” published in 1970, Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor has laid out the meaning behind her book’s name and her full intent within. But no primer quite equips the reader for the free verse that follows — an exhale of recipes, memoir, travelogue, social commentary and gossip that illuminates one Black woman’s experience like no work of literature before or since.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

At the near end of a year for which there are no words left, when many of us are returning to or doubling down on isolation to help stave off further crisis, I hope this slim, powerful volume finds its way into your hands. Generations of food writers have gloried in the ways it shattered writing structures. “Vibration Cooking” didn’t receive the level of praise it deserved when it was first released, but its genius rose through the white-dominated publishing industry and found a lasting audience. In its 50th year, Smart-Grosvenor’s debut book remains an urgently prescient read.

As Smart-Grosvenor explains in the introduction of a later edition, she was living in New York with two young daughters, yearning for creative expression but with little money to pursue an outlet like taking a class, so she borrowed a friend’s typewriter and asked herself what she knew to write about. Cooking was the answer. An editor at Doubleday saw the manuscript for “Vibration Cooking” along with a book of poems by Smart-Grosvenor’s then-9-year-old daughter (sculptor and artist Kali Grosvenor-Henry) and published them both.

Most of the recipes come in the form of quick, conversational instruction, often an offshoot of the flowing narrative. Some dishes (Hoppin’ John, red rice, smothered rabbit) demark her early upbringing in South Carolina Lowcountry, among its Gullah-Geechee culture influenced by West African dialects and traditions. Her family moved to Philadelphia in her later childhood, and the cooking winks at adaptation. This is the sum tutorial for her grandmother’s recipe for mountain oysters: “Cut mountain oysters in half and parboil for 10 minutes. Then season to taste. If they are too thick then dip in Aunt Jemima pancake flour. Fry in fat.”

From travel and family and friends, there is talk of Jamaican curried goat and salt fish cakes; ham omelet layered with onions and peppers; ground nut stew and feijoada and lima beans with baked breast of lamb.

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

We follow her mind from story to recipe to one lucid observation after another: “The slaves were just adapting to a language that wasn’t their own. They were from many tribes, and plus the masters didn’t talk too tough themselves. So they took the English language and did what they could with it and it was beautiful. Black people are the only people in this country who speak English and make it sound musical.”

Among some correspondences she includes is an excoriating letter to the editor addressed to Time magazine in reaction to an article on the “soul food fad.” It’s legendary.

The last section of the book is two pages — a poem and a note about the importance of the kitchen — and it’s called “To Be Continued.” It elicits a long pause.

Smart-Grosvenor died in 2016 at 79. She led a big, self-directed life. Among articles and subsequent books and the occasional acting gig, she was a commentator for NPR for three decades; she viewed her work as culinary anthropology. Filmmaker Julie Dash is developing a documentary about her.

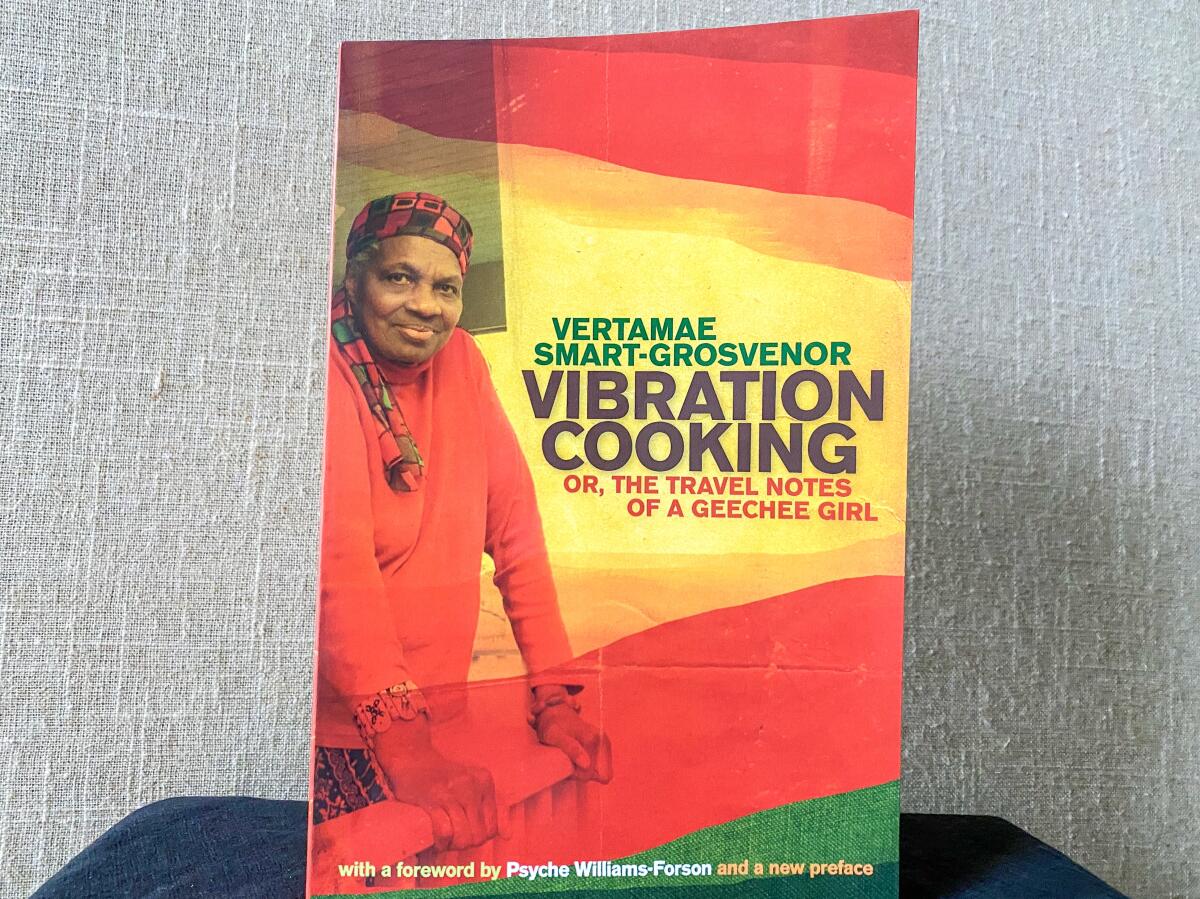

“Vibration Cooking” has slipped out of print and back in again over the years. The University of Georgia published the latest, still-available edition in 2011. I had an earlier version; it had a map of South Carolina on the cover and a smiling picture of Smart-Grosvenor in a yellow dress and orange hat, one shoulder angled slightly and stylishly higher than the other. I lost it during my last year of full-time travel for work, and I’m still mad about it. But the latest edition has a rich, academic foreword from Psyche Williams-Forson and a new preface from Smart-Grosvenor in which she continued telling truths: “It was said that slaves brought okra. Watermelon. They carried benne seeds over in their ears. Did they pick up their watermelons at the baggage claim? Education is the key.”

So is reading this book, for the first time or the fifth.

Our stories

Last week Ben Mims laid out his 2020 vision for Thanksgiving dinner. This week the food team considers how to make the most of leftovers:

— I wrote about my favorite day-after cooking project — Sara Roahen’s turkey bone gumbo — which she updated with tips for making the roux in the oven.

— Jenn Harris shares her family’s strategy for turkey fried rice.

— Julie Giuffrida takes cues from “Will It Waffle?” by Daniel Shumski and transforms leftover stuffing.

— And Brian Park shares memories of family and sharing Thanksgiving leftovers in Ensenada.

Beyond the holiday table, Lucas Kwan Peterson reports on how small, family-owned farms are struggling through the pandemic.

Alejandra Reyes-Velarde writes about how the 10 p.m. curfews issued from Sacramento this week will affect late-night restaurants and bars.

Wishing you a safe and peaceful Thanksgiving in whatever way you spend the day this year.

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.