Best art in 2017: Our critic’s top 10 exhibitions, plus one very big worry

Art museums, which are not for profit, now coexist uneasily with a hyper-aggressive art market, where making bare-knuckle profit from luxury goods reigns supreme. For museums the stress shows, and often it’s not pretty.

- In Massachusetts, the attorney general had to intervene to stop, at least temporarily, the sale of 40 paintings that are the cream of the Berkshire Museum’s collection — an unethical plan to raise upward of $60 million to fund operations.

- In the Netherlands, the director of the prestigious Stedelijk Museum was forced to resign following revelations that, for hefty fees, she was running a private art advisory firm on the side.

- In Venice, Italy, Damien Hirst sold more than $300 million worth of his new work not from a gallery but directly out of a museum show.

- At the new Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, a gallery owner, Honor Fraser, was invited to join the board of trustees — an eyebrow-raiser that created an inevitable perception of conflict of interest when the ICA opened with a major commission from Sarah Cain, an artist represented by Honor Fraser Gallery.

- Hollywood movie director and producer George Lucas secured public land in Exposition Park to erect a billion-dollar museum for something called “narrative art,” a made-up category.

There are plenty more examples. Money pressures shape art museum activities in ways that go from mini to mega.

FULL COVERAGE: Year-end entertainment 2018 »

This year the buoyant upper reaches of the art market ballooned in a way that seems unimaginable. Nearly half a billion dollars traded hands for a banged-up, heavily restored panel originally painted by Renaissance genius Leonardo da Vinci. Four bidders vied for it, two pushing the painting to a price almost twice as large as any known prior art sale.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

The buyer is reportedly the Abu Dhabi Department of Culture and Tourism. Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, 32, did the bidding. He has sent the painting to hang in the Louvre — not the one in Paris, but the newly branded one in Abu Dhabi, capital of the United Arab Emirates, a federation of absolute monarchies.

The painting, now world-famous because of its headline-grabbing price, cost almost what the entire 55-building museum complex cost. (The published estimate is $650 million.) A prominent young Muslim flouted his conservative religion’s traditional stricture against owning figurative images to procure the icon. He has been promising to champion “a more moderate Islam,” but either way the flashy loan cements the new museum’s dual function as trophy house and tourist trap.

The Leonardo sale was described by more than one observer as “mad.” Maybe. What is certainly mad is what the transaction represents, which is the colossal — and still-growing — gulf between the billionaire class and everyone else.

Good things of course continue to happen in museums — in L.A., most notably, the Getty-funded initiative to underwrite a slew of exhibitions of Latino and Latin American art, the emergence of the long-sleepy California African American Museum as a lively destination and the announcement that a museum will be built at UC Irvine specifically to trace the development of California art. Here, in chronological order of their openings, are the 10 best museum exhibitions I saw in Los Angeles this year:

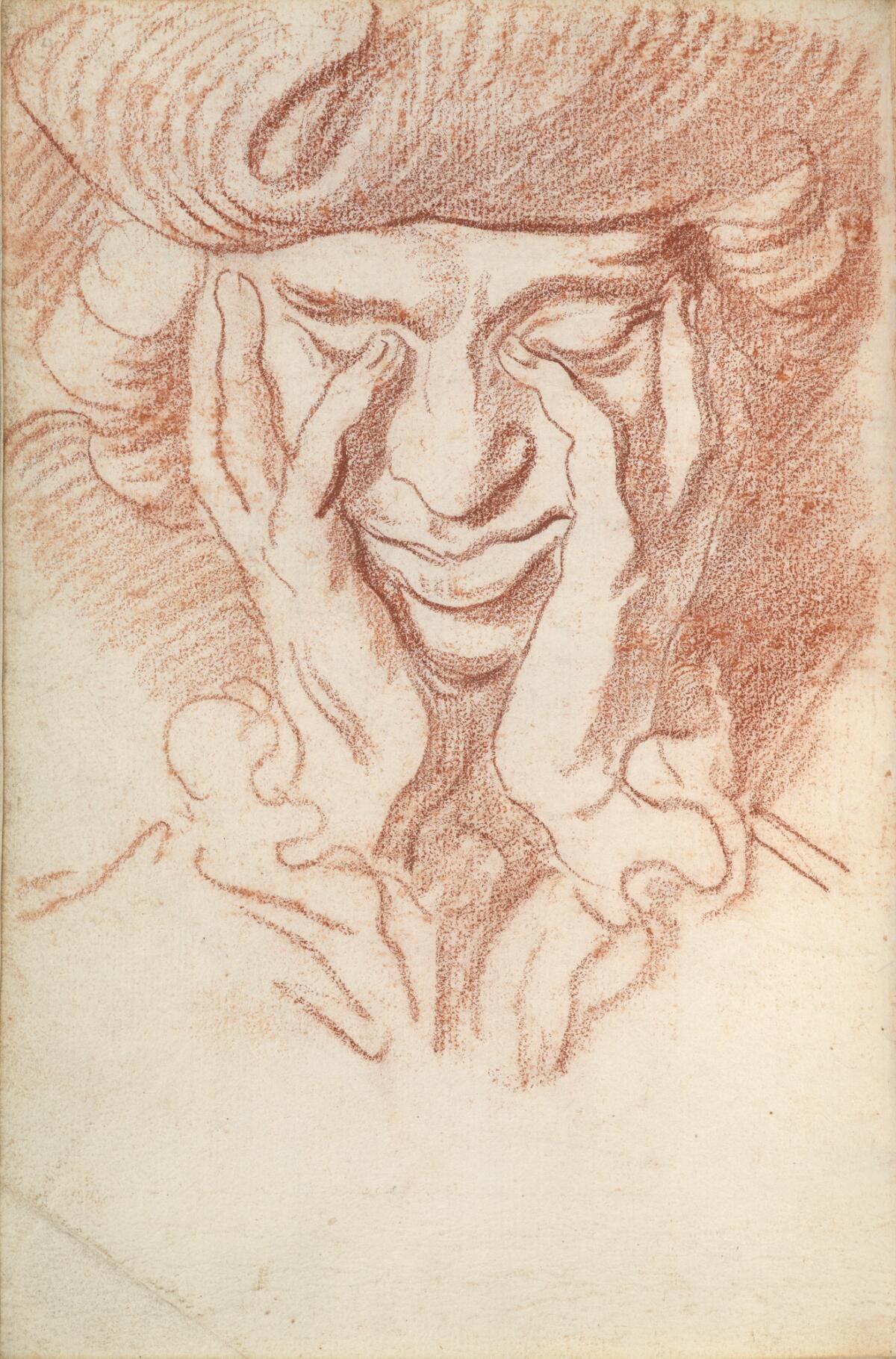

“Edme Bouchardon: Royal Artist of the Enlightenment” at the J. Paul Getty Museum. When you’re the court sculptor and the aristocracy is being toppled, don’t expect your career to have a long shelf life. That’s one lesson in this revealing survey of a largely forgotten artist from French King Louis XV’s reign. The other is that brilliant drawings can be an extraordinary guide to sculpture.

“Jimmie Durham: At the Center of the World,” UCLA Hammer Museum. Is human identity genetic or cultural? Is it determined by DNA or by government decree? Is it authentic and fixed or fictional and fluid? In 200 sculptures, drawings, collages and videos, expatriate American artist Jimmie Durham located one’s own conception of self as the nucleus of things.

“Moholy-Nagy: Future Present,” Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Hungarian avant-gardist Laszlo Moholy-Nagy kept his art moving forward throughout the first half of the 20th century, an era defined by war, dislocation, poverty and epic upheaval. Moholy-Nagy emerged in the show as less a Utopian than an indefatigable optimist.

“Kerry James Marshall,” Museum of Contemporary Art

Black paintings, a distinct and widely celebrated category of postwar American abstraction, took on a whole new meaning in Marshall’s often moving representations of black life since the 1950s. The show more than deserved the crowds piling in to see it.

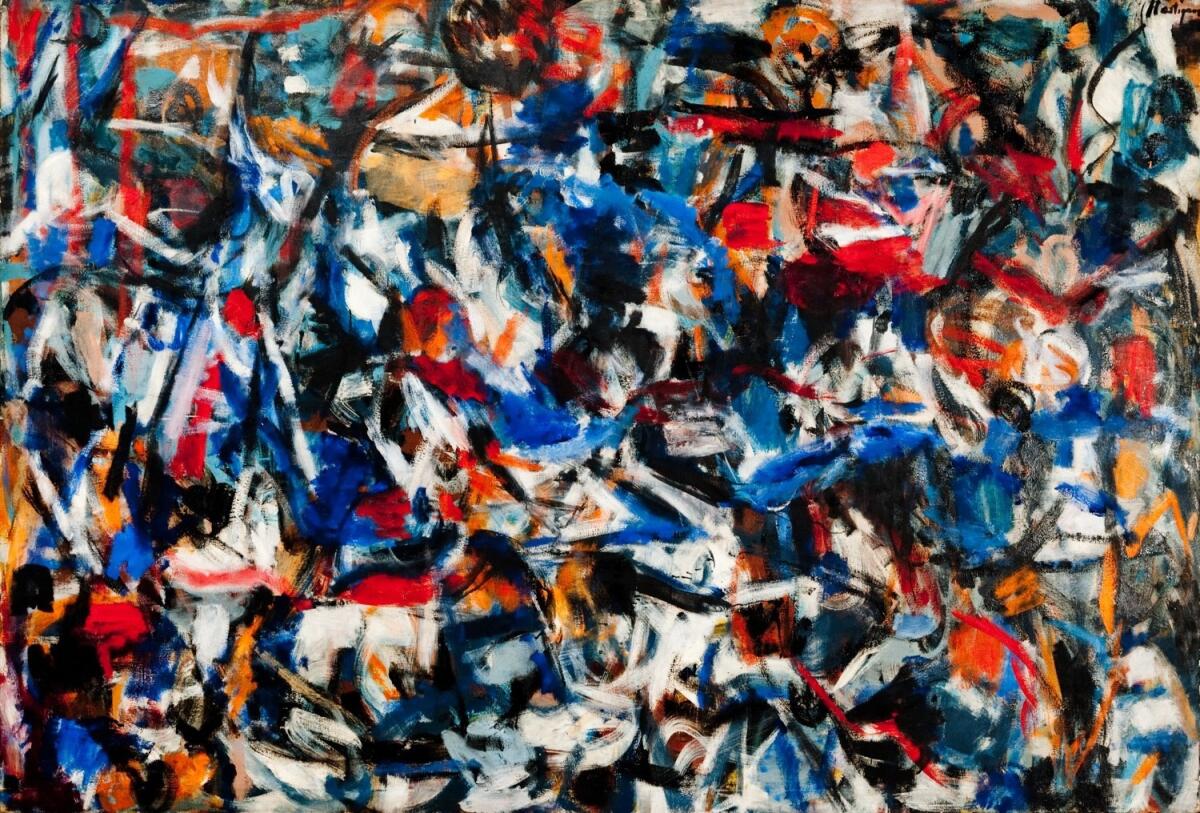

“Women of Abstract Expressionism,” Palm Springs Art Museum

No need to downgrade Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning or Clyfford Still to recognize the greatness of painters Jay DeFeo, Lee Krasner and Joan Mitchell. And Ethel Schwabacher, an artist hitherto virtually unknown to me, was another revelation, lesser but notable, in this survey of a dozen artists working in San Francisco and New York from the late 1940s to the early 1960s.

“Anna Maria Maiolino,” Museum of Contemporary Art

In the late 1960s, Brazilian artist Anna Maria Maiolino began making marvelous drawings in which line was achieved by tearing the paper, and space was created by physical dislocations of the material. Drawings as sculptures (and vice versa) have been a remarkable leitmotif ever since. (On view through Jan. 22.)

“Martin Ramirez: His Life in Pictures, Another Interpretation,” Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. The great self-taught draftsman Martin Ramirez, an émigré from Mexico to Northern California in the 1920s, got his first L.A. survey — about 50 works — as the debut exhibition of the reconfigured Santa Monica Museum of Art, now operating in downtown L.A. with a new name. (On view through Dec. 31.)

“Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985,” UCLA Hammer Museum. A great big, sprawling brawl of an exhibition with a few paintings and sculptures and mostly Conceptual and camera-based art, “Radical Women” featured 120 Latina and Latin American artists from the United States and 14 additional countries. If you were familiar with more than about 12% of them going in, you did better than me. (On view through Dec. 31.)

“Giovanni Bellini: Landscapes of Faith in Renaissance Venice,” J. Paul Getty Museum. The lay of the land in a painting by Giovanni Bellini, ground zero of the Venetian Renaissance, is a coded assembly of dirt, rocks, water, trees and sky, all with profound meaning for the people shown within it. This gem of an exhibition — perhaps we should say landmark — is the first by Bellini in the United States. (On view through Jan. 14.)

“Painted in Mexico, 1700-1790: Pinxit Mexici,” Los Angeles County Museum of Art. By the end of the 18th century, most of the money in circulation in New Spain and over half of the country’s land was under control of the Catholic Church. Painting became a distinctive promotional tool. This first-ever survey of the sumptuous, late Baroque era is a spellbinding overview, filled with art at once brilliantly inventive and often wonderfully weird. (On view through March 18.)

christopher.knight@latimes.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.