Review: ‘Radical Women’ at the Hammer Museum is a startling show you need to see, maybe twice

- Share via

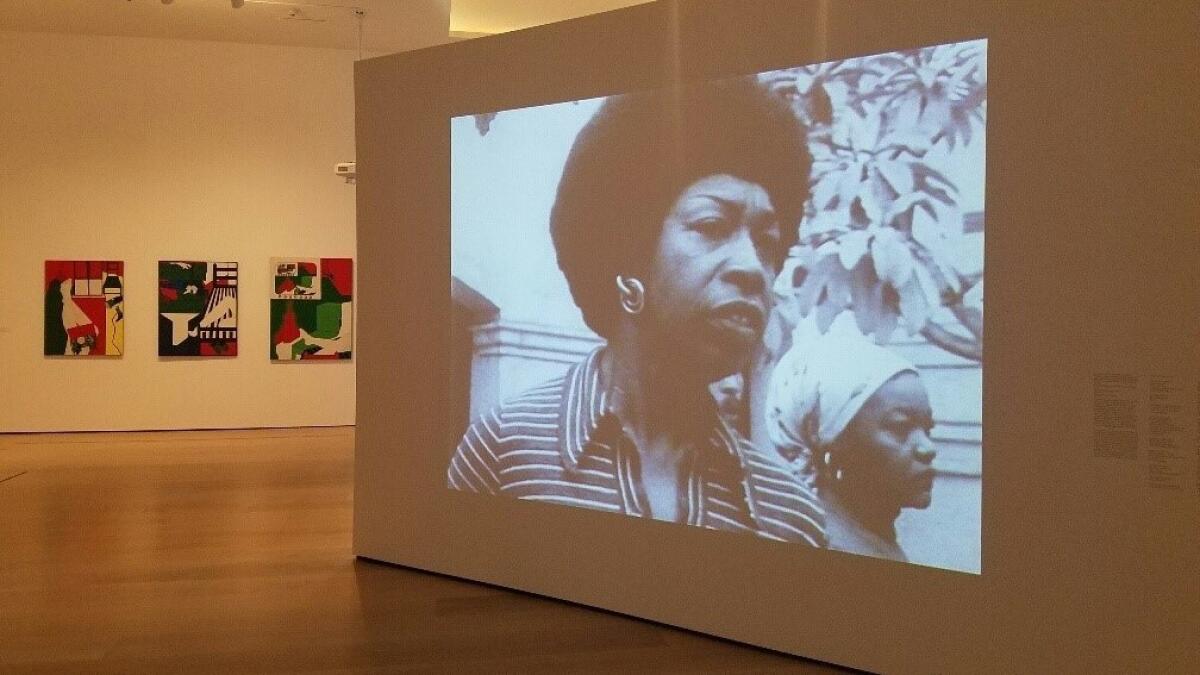

Afro-Peruvian poet Victoria Santa Cruz welcomes visitors to the UCLA Hammer Museum’s “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985” with a blast of energy so powerful that it will stop you in your tracks, then propel you through a mammoth exhibition that unfolds in seven sprawling chapters.

It’s a kick.

“Me gritaron negra” is a spoken-word poem captured in a short black-and-white 1978 film, photographed by Eugenio Barba, transferred to video and projected larger than life-size on the wall just inside the show’s front door. Santa Cruz, backed by a chorus of three women and three men, one driving the song forward with the insistent rhythm of a cajón, a wooden box-drum, recites a fierce avowal of her identity through unwavering voice and the focused choreography of body language.

“They shouted black woman at me,” the title says. “Black!” Santa Cruz and her chorus repeat. “Black, black, black, black, black, black!” The words are barked out in a clamorous call and response.

The performance was born of the festering childhood memory in which a little blond white girl refused to play with 7-year-old Victoria because her skin was black. Santa Cruz’s play group suddenly, inexplicably followed suit, shunning her.

After years of self-denial, the poem reveals, she tired of the angry victim role. Santa Cruz embraced the taunt of “black!” — absorbing the word into her skin and transforming it into a shout of liberation. Incorporating clapping elements from zamacueca, a mostly forgotten colonial dance with roots in African, Spanish and Andean rhythms that originated in the Viceroyalty of Peru, she moved from the periphery of her own life’s experience to land squarely in its center.

There is no revolution without evolution, Santa Cruz once said, and this bracing performance, recorded when she was 56 (she died at 91 in 2014), is testament to it.

“Radical Women” is a great big avalanche of an exhibition, an exciting rush of work by scores of artists almost entirely unknown outside their home countries. Of the show’s 120 Latina and Latin American artists from the United States and 14 additional countries, I had a working knowledge of a grand total of 15; the rest, including Santa Cruz, were new to me.

A fascinating cross-section of a tumultuous time and expansive place, it’s a shining example of why Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, the citywide Getty initiative, is so important. Liliana Porter’s elegant, conceptually marvelous photographs are a worthy metaphor: She drew a pencil line down a finger, extending it onto the ground depicted in the photograph and then across the matte that frames the picture, finally extending it out of the frame and onto the gallery wall. The line of Porter’s absent finger marks the room in which you stand.

With more than 250 works, the show is also daunting. Be prepared for a lengthy visit — or repeat visits, easy enough since the Hammer has free admission — to get a handle on things. (I’ve been twice.) Don’t expect a masterworks display; this is not that kind of show.

Instead, guest curators Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta, scholars in the burgeoning field of Latin American art history, have fashioned a sweeping overview. They have created a context within which the work of individual artists might be more clearly seen.

The late Cuban artist Ana Mendieta, for example, is among the most widely known artists in the show. A short film documents a 1975 performance in which she lays down atop a rock on which she has poured crimson liquid in a shallow, body-shaped cavity dug into the mud. The cavity is part grave, part womb. In a ritual of mortality and regeneration, her body merges with natural surroundings at the edge of a lake.

Nearby, a 1966 painting by Colombian artist Delfina Bernal, who is far less familiar, shows abstracted and fragmented body parts fused with the watery curvature of an aquatic environment. Like “Slow Swirl at the Edge of the Sea,”

Rothko worked in the blistering wake of World War II. Bernal, who now lives and works in Northern California, grew up in an era of Colombian civil war. Mendieta, daughter of a Cuban political prisoner, was inspired by the ritualized violence in art by groups such as the Viennese Actionists.

One difference between the American painter and the Latin American artists: Sexism is institutionalized in the United States, but these women were dealing with authoritarian regimes where it was even more deeply entrenched. One of the show’s important lessons, however, is the hesitation of Latin American women to embrace the rising wave of feminist consciousness of the 1960s and 1970s.

These artists are hardly indifferent to their gendered situations. Throughout the show, a woman’s body is considered as both a physical entity and a social construction. But American imperialism, which had been playing out for decades in the Southern Hemisphere, made it impossible for the political left to regard feminism in a fully favorable light.

The show’s curatorial chapters kick off with the body as a subject of self-portraits, such as Santa Cruz’s. They continue with bodies as landscapes, performance instruments, physical and psychological territories and more.

Camera work is ubiquitous, in numbers far greater than other mediums. The first two galleries are typical: 35 photographs, films and videos and just 10 paintings, sculptures and mixed media works.

In a life-size photographic triptych, Mexican artist Lourdes Grobet shows herself emerging into the light like Botticelli’s Venus — not borne in by the sea, but stepping through a silvery veil, which stands in for the surface of a photograph. L.A.-based Patssi Valdez, assuming various photographic poses of self-identified power figures, stares down a viewer with unblinking intensity.

Brazilian Regina Vater, coinciding with Cindy Sherman’s 1978 “Untitled (Film Stills),” photographed herself in a dozen clichéd roles — mom, vamp, school girl, librarian, etc. Framed together, they disassemble the limitations of social stereotypes, transforming the single sitter into a multifaceted kaleidoscope of characters. What unites them is the uniformity of her eyes.

Today it can be difficult to recall that, before the last 30 years or so, camera images were contested as art or else corralled into a second-class ghetto. That women artists in large numbers would shun established mediums such as painting and sculpture and turn instead to still, movie and video cameras is hardly surprising, given their own similarly constricted social and cultural standing.

Documentary snapshots of Sylvia Palacios Whitman show her in white pants and tank top straining against a taut elastic cord wrapped around her waist. Her body is pictured as the projectile in a giant “Sling Shot,” the camera a determined David poised to slay an unseen Goliath.

Art, especially painting, would appear to be the unobserved adversary. In a witty 1982 video, Venezuelan Ani Villanueva, swathed in an abstract costume of painted canvas, becomes a mesmerizing “Moving Picture” in a slow-motion ramble through a white-walled gallery with mediocre abstract art enshrined on the walls.

Unlike most painting and sculpture, camera work often involves communal labor — not the solitary artist alone in a studio producing refined objects, but an artist working with camera operators, costumers, performers, scenic designers and more. As a person, Santa Cruz shouted “black!” in self-identification; but, as an artist at the center of a film, she might also have shouted “camera!”

Some artists did make compelling paintings and sculptures, the most familiar being Maria Sol Escobar, known as Marisol. A self-portrait, her figuratively painted blocks of carved wood are notable for being hybrids of two mediums.

One of the most startling works is an intimate, horizonless, seemingly unassuming landscape painting of tall grasses rendered by Argentine artist Diana Dowek in slashes of glowing color against a black ground. In the lower right corner, a picture within the picture reveals itself as a car’s side-view mirror, in which first one, then two disheveled corpses are seen sprawled in the grass. There, the horizon is glimpsed at a 45-degree angle; the dangerous world reflected from behind a viewer has gone topsy-turvy.

Revealingly, the section of the show with the largest concentration of paintings and sculptures is focused on erotic art. Among them are an abstract shaped canvas of swollen, interlocking forms by Cuban Zilia Sánchez and Colombian sculptor Feliza Bursztyn’s “Bed” — a languid, horizontal form draped in red satin that periodically vibrates. Cameras can record erotic subjects, but the surface of a photograph or TV screen is rarely sensuous itself, the way painting and sculpture can be.

It is worth noting that, in an informative wall text featuring a 25-year timeline of political and social events in all 15 countries, almost every list begins the same way. Followed by citations such as the availability of legalized divorce and contraception, they typically start with the date when women gained the right to vote.

Social movement is always knotty. Voting rights, which represent individual power in participatory government, came for most women in Latin America only after the global upheaval of World War II.

However, since receiving the franchise was followed by a steep rise in repressive Latin American governments, including outright dictatorships, one is left to wonder: To what degree does authoritarianism rear its head as an establishment reaction to base fears aroused by social equality for women?

In the wake of our own 2016 presidential election, when an unqualified but unreserved authoritarian prevailed over a powerful woman who was the first to top a major political party’s ballot, “Radical Women” assumes an unexpected timeliness. Although initiated long before the political campaign as part of PST: LA/LA, think of the Hammer exhibition as the women’s march of art.

Find all of our coverage of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA at latimes.com/pst.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985’

Where: UCLA Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood

When: Through Dec. 31; closed Mondays

Info: (310) 443-7000, www. hammer. ucla.edu

christopher.knight@latimes.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

MORE REVIEWS:

'Kinesthesia' exhibit in Palm Springs spotlights kinetic art in breathtaking new dimensions

Anna Maria Maiolino at MOCA, Carlos Almaraz at LACMA

The remarkable drawings of Martín Ramírez at ICA LA

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.