Review: Edmé Bouchardon’s extraordinary drawings changed the way sculpture looked

- Share via

If you find that the name Edmé Bouchardon doesn’t ring a bell, you are far from alone.

Just around the time 18th century France was unraveling in bloody revolution and Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette were getting guillotined, the once-famous sculptor’s big reputation likewise got chopped. Bouchardon had been royal sculptor to Louis XV, grandfather to the deposed and now-beheaded king.

Grandpa was not ignored, either — at least metaphorically. Revolutionary mobs toppled Bouchardon’s monumental bronze equestrian sculpture of his aristocratic patron, decked out like Emperor Marcus Aurelius while prancing on horseback atop a high perch. The sculpture stood for 34 years in what is now Paris’ Place de la Concorde, its artistic design and skillful execution widely acknowledged among connoisseurs as a sign that France was every bit the modern-day equivalent to glorious ancient Rome.

The only fragment of that extravagant monument to Louis XV that remains intact today is the very last object at the end of a large and enlightening exhibition newly opened at the J. Paul Getty Museum. Ironically the fragment — a big, chunky right hand — once grasped the royal scepter, emblem of imperial authority.

Louis’ hand is sculpted in broad, simplified forms — curved tubular fingers extending from a soft but boxy base. Surprisingly, fingernails and wrinkled creases in the skin between thumb and forefinger and across the knuckles also mark the hand.

These humble details of physical anatomy seem odd, if only because the finished sculpture was 17 feet tall and rested atop a multi-part stone pedestal that brought the entire ensemble to twice that height. Standing at the base of the pedestal looking up at the mounted figure with sceptered hand raised, a viewer would see none of it — not a crinkle, crease or cuticle.

But they are there. In many respects, the duality of carefully wrought, formal simplicity married to acuity of naturalistic detail embodies Bouchardon’s significance as an artist. His work nudged the visually delightful excesses of Rococo art toward the more sober gravity of Neo-Classicism. In more ways than one, the sculptural fragment that concludes “Bouchardon: Royal Artist of the Enlightenment” really is “the artist’s hand.”

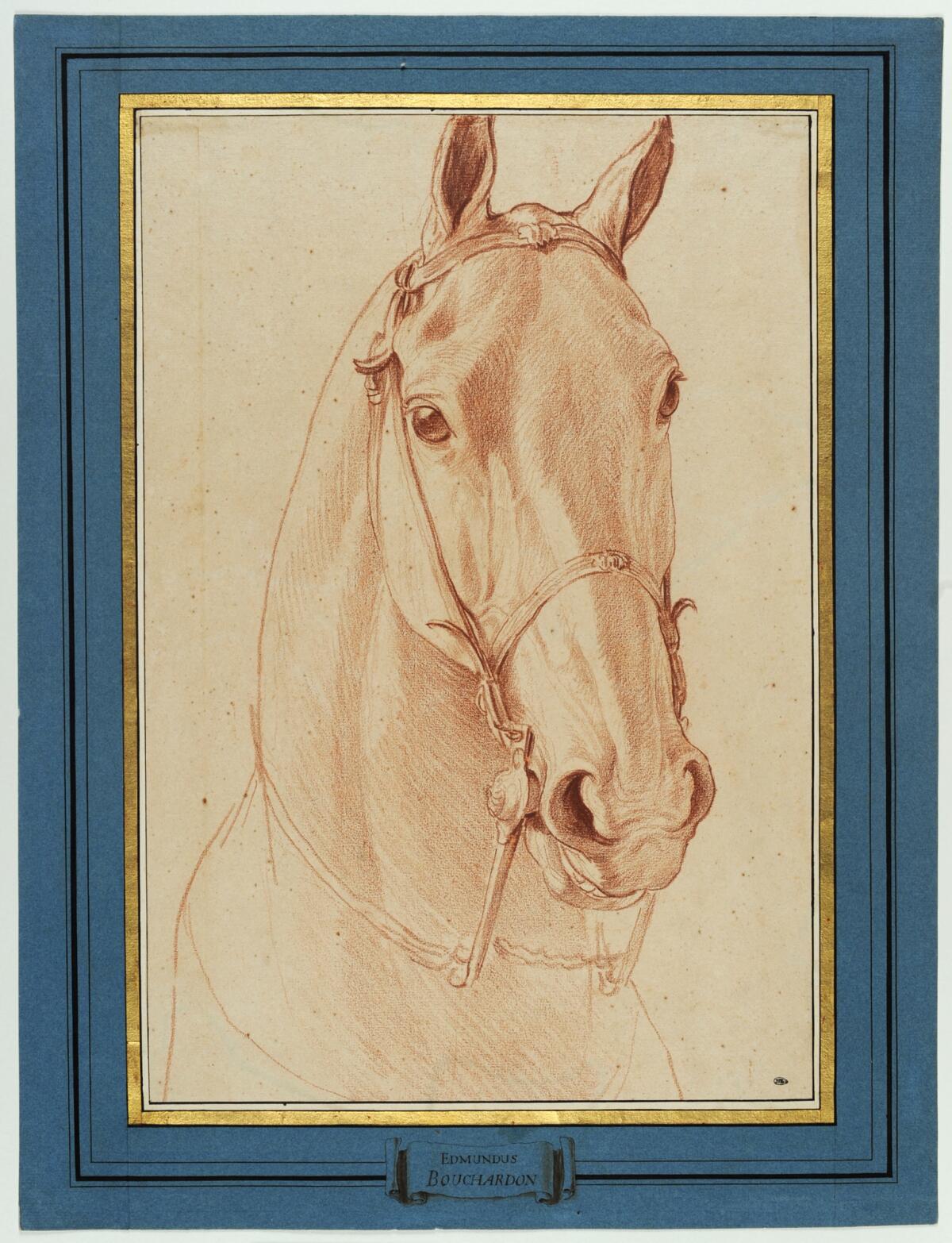

The fragment is accompanied by eight large and fascinating drawings for the monument in which Bouchardon analyzed the horse and rider as anatomical creatures — their physicality, posture and material bearing. One is an écorché, an exquisite frontal rendering of the horse in red chalk with its skin removed to display the underlying musculature. Every hidden sinew is carefully annotated in an identifying list carefully written along the drawing’s edge.

The drawing is emblematic of the arduous academic training Bouchardon and other artists of his natural skill and cultural ambition received. Born at Chaumont about 170 miles southeast of Paris, Bouchardon was the son of a successful if minor architect and sculptor. He won the Prix de Rome in 1722, when he was 24, the first young sculptor to snag the prize in years, and he spent the next nine years in Italy copying Classical statuary and Renaissance art.

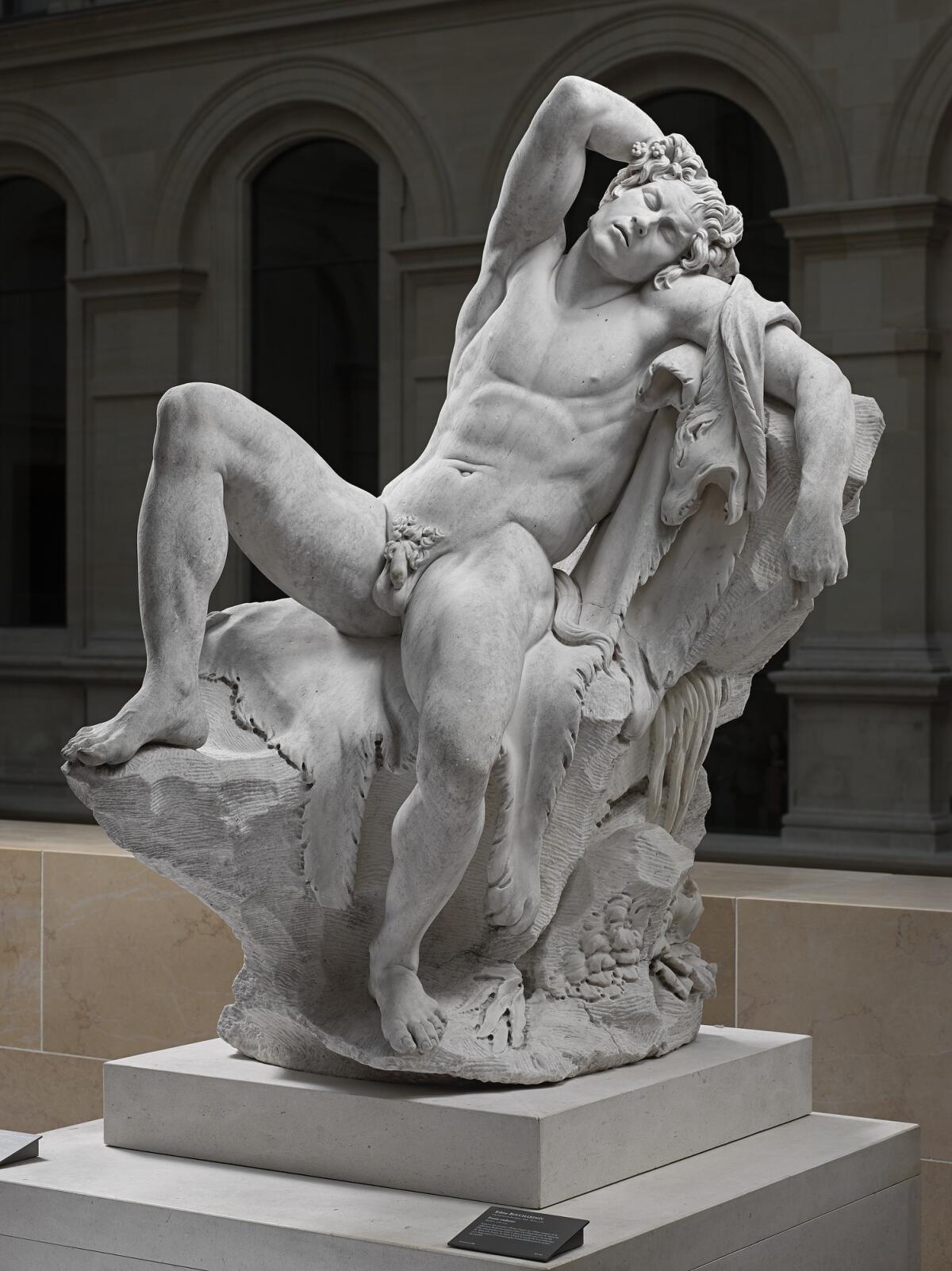

The show opens in the Getty rotunda with the sculpture Bouchardon made to fulfill a requirement for having won the prize. A full-scale copy of the famous Barberini Faun, a Hellenistic sculpture believed to have been carved in the late 3rd or early 2nd century BC, it shows a naked satyr apparently sleeping off a drunken binge. His legs are provocatively splayed in what is surely Western art history’s original — and still most dramatic — example of man-spreading.

Bouchardon’s slightly altered copy, rather than being made to reproduce a cast of the original, was carved from a study-model the artist also made from scratch. Like an ice cream cone on a warm summer day, his faun seems almost to melt into the stone on which he sprawls, drooping atop a limp animal skin. The degrees of separation from the crisply articulated original resulted in a softer, more sensuous figure with less chiseled muscularity.

The shift to a more supple form is perhaps a legacy of the Rococo era’s sexier stylistic sympathies. So how did Bouchardon get to the more linear style of Neo-Classicism of which his later sculptures were a harbinger of things to come?

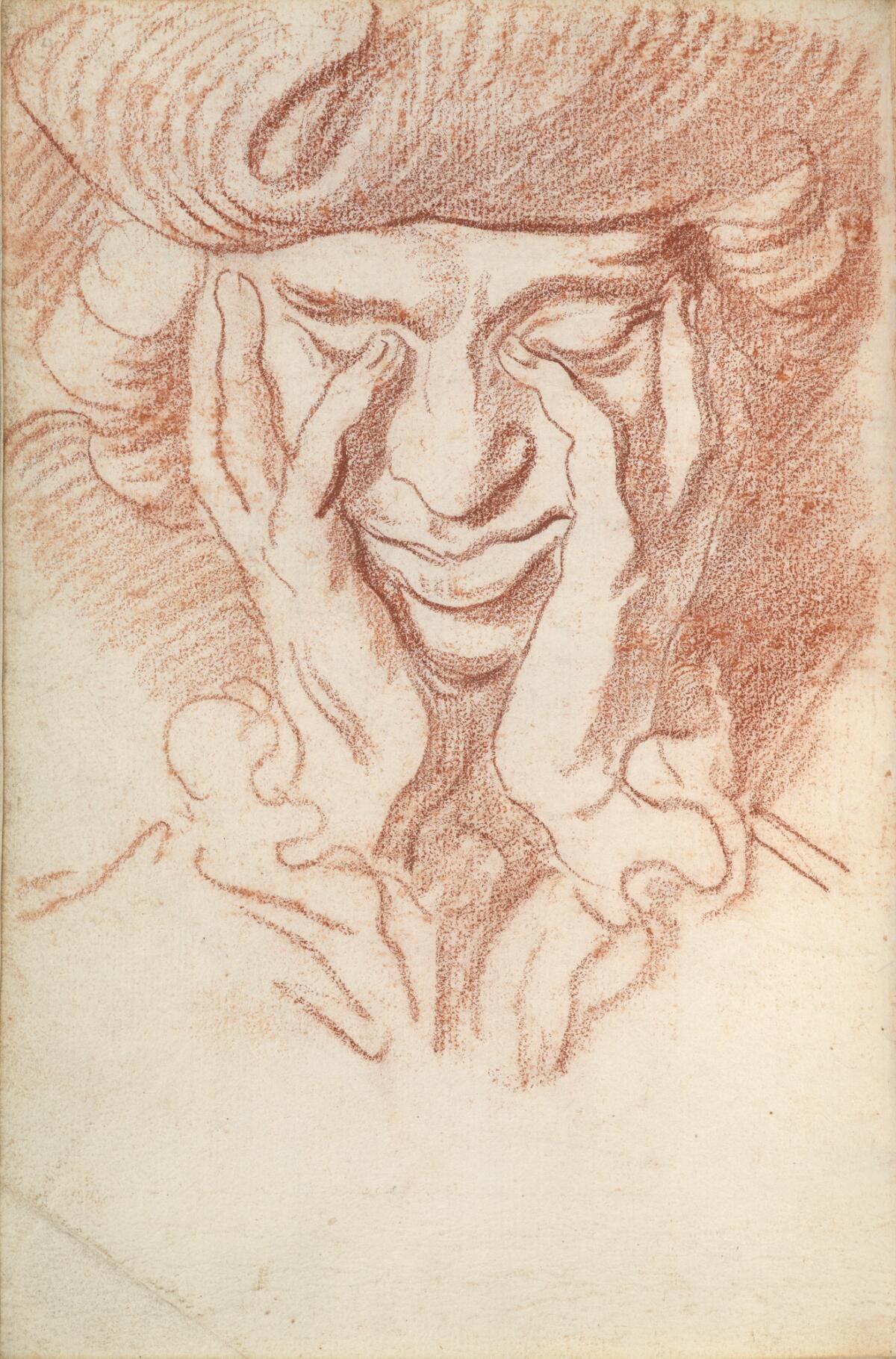

By relentless drawing, I’d say. Bouchardon was an exceptionally talented draftsman, and it seems to have had a profound effect on the direction his sculpture took.

The bawdy faun sculpture and the eight monument drawings belong to the Louvre Museum. The show was organized in association with the Louvre, where it was seen last fall, by Getty curator Anne-Lise Desmas and Harvard Art Museums’ curator Edouard Kopp.

One surprise is that fully half the 146 works on view are drawings on paper, usually in red chalk. (The rest are sculptures, carved reliefs, paintings, plaster statuettes, terra cottas, medallions and engravings, some by other artists.) As a student he drew everything in Rome from antique to Baroque sculptures — from the celebrated Apollo Belvedere, all poised restraint, to Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s explosive sunburst, “Glory,” at the Vatican.

Among them is an exquisite drawing of Camillo Rusconi’s “St. John the Evangelist,” an imposing sculpture for a niche in the Lateran basilica. John is shown in ecstatic mid-inspiration, quill pen in one hand and oversized manuscript in the other. His head tilts heavenward, hearing divine utterances.

In a wonderful Rusconi detail, the heel of the robed figure’s right foot lifts slightly off the ground, as if he’s about to lift his entire body up into the air on angelic flight. Bouchardon’s linear strokes of red chalk alternate with and are surrounded by an abundance of blank paper, filling the image with light. He transforms Rusconi’s heavy marble into something simple and ethereal.

In these and other chalk drawings of sculptures and marble reliefs, Bouchardon is transforming mass into line. The linearity of Neo-Classical sculptural style is just a short step away.

That’s one primary thread the chronologically organized exhibition follows. It starts with his time in Rome, where he carved several portrait busts of British tourists and members of the papal court. Bernini looms large as an influence.

Next comes his work on fountain designs, inspired by a competition for the Trevi Fountain. He lost. When he returned to Paris, though, he won dozens of fountain commissions, only two of which were built: one at Versailles, the other a landmark symbolizing the four seasons on Rue de Grenelle.

A small section dominated by a big, larger-than-life “Virgin of Sorrows” looks at religious and funerary art. The 8-foot “Virgin” registers as something of a turning point in the show’s narrative.

The drama of her grieving swoon is conveyed not by flourishes but by sobriety — broad, smooth, unadorned garments counterpoised with deep shadows cast in their folds. Against these sweeping shapes of light and shadow, the delicacy of Mary’s diminutive hand and face creates a startling emotional fragility.

The show stealer, though, is the impish yet elegant, magnificently complex figure showing “Cupid Carving a Bow From Hercules’s Club,” finished when the artist was 52. (He died 12 years later in 1762.) In the myth, the clever boy captured the sword of Mars, god of war, to use in cutting down the human hero’s mighty weapon into a bow that could propel arrows of passionate ardor.

When he heard of it, no less a critic than Voltaire worried that a sculptural depiction of the god of love shown in the act of carving would be regarded as a veiled reference to Bouchardon’s own activity as a sculptor, busily chipping away at marble. Voltaire was right about that, but on the magnificent evidence of the result, he need not have worried.

“Bouchardon: Royal Artist of the Enlightenment”

Where: Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood

When: Through April 2; closed Mondays

Information: (310) 440-7300, www.getty.edu

christopher.knight@latimes.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

ALSO

In postwar L.A., youth style intersected with social justice

Building Type: Introducing a weekly column on architecture

The artist who made protesters' mirrored shields Standing Rock

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.