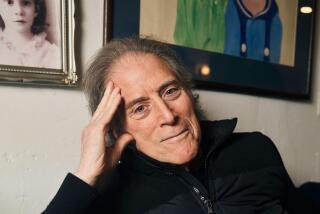

Stan Freberg: brainy, playful and a master of irony

Stan Freberg, a great man of comedy and of commercials, died Tuesday at the age of 88. His career ranged wide, from cartoon voice-overs and puppetry to satirical hit records and radio series to Clio-winning ad campaigns. Yet it all seems very much of a piece, the product of a distinct, mischievous, instantly recognizable sensibility.

When, on the fourth-season premiere of “Mad Men,” Peggy (Elisabeth Moss) goes back and forth with a colleague in a conversation consisting of her passionately addressing him “John” and him calling her “Marsha,” it was a nod to Freberg and his 1951 hit record, “John and Marsha,” a soap opera scene whose only dialogue is those names, spoken with varying passion and emphasis.

It was the first of many singles he made for Capitol Records, culminating in his 1961 masterpiece, “Stan Freberg Presents the United States of America, Volume One: The Early Years,” a meta-comical musical that revised American history from Columbus through Yorktown, and bits of whose dialogue regularly emerge from the corners of my mind: “You tell ‘em, Bix,” “Surly to bed, surly to rise,” “Rumble rumble rumble, mutiny mutiny mutiny,” “French horns.”

For someone whose personal appearances were relatively infrequent — on variety shows and talk shows, in a handful of sitcom guest shots and movie roles — his face was surprisingly familiar. (It was a child’s face, all his life.) But it was by his voice — in cartoons for Warner Bros. and Walt Disney, in the Emmy-winning early-’50s puppet show “Time for Beany,” on his records, and in his commercials — that we knew him.

By the time that “Mad Men” episode was set, in late 1964, Freberg was an established ad man himself with a one-man boutique firm, Freberg Ltd. (But Not Very). Ars Gratia Pecuniae — “Art for money’s sake” — was its mocking mock motto.

America in Freberg’s creative heyday, which stretched from the Korean through the Vietnam wars, was a place of hope and dread, of consumerism exalted and materialism decried. Advertising was in the thick of this, surfing the cultural tides (or beating against them), engineering the future (or attempting to). Freberg’s commercials were a critique of commercials, and because he was the outsider on the inside, he could seem subversive, even selling soup.

His office was not on Madison Avenue but on Sunset Strip, down the street from where Jay Ward, a kindred comic spirit, made “Rocky & Bullwinkle” and “Fractured Flickers.” That he worked in advertising even as he ridiculed it didn’t seem a contradiction; in fact, one thing enhanced the other. He had his cake and ate it too, while shouting, “Look at this ridiculous, yet delicious cake!”

It helped that his clients tended to be homely things — frozen pizza, tomato paste, Chinese food, tin foil, dried fruit — which he sold in ironically inflated terms, in a stentorian voice.

“Giblet gravy and sliced turkey, together in the most significant frozen dish of our time, Buffet Supper.”

Of a prune: “Today the pits, tomorrow the wrinkles — Sunsweet marches on.”

To an eager yet doubting young mind, there was something worth learning from this ironically heroic attitude. Freberg was brainy (he looked smart too, like a moderately hip rocket scientist) but playful. He was a connoisseur of small absurdities, offended by the larger, deadlier ones: “Incident at Los Voroces,” a Cold War allegory that recounted the escalating rivalry between two rival casinos, the Rancho Gomorrah and the El Sodom, that Freberg created for his short-lived 1957 CBS radio-show ended in an H-bomb blast.

Comedy remade itself in these years. It became more serious, more absurdist, more analytical, more political, more engaged in and critical of the social moment. Freberg’s comedy for comedy’s sake, and his comedy for the client’s sake, were born from the same satirical point of view. His real ads, as on his comedy records, often parodied other ads or functioned as critiques of advertising itself, highlighting its machinations, its institutional dishonesty. Some had little to do with the product itself or recontextualized it, as in an ad in which Jesse White, a regular member of Freberg’s company of players, wielded a hot dog like a cigar, or one in which a lawn mower was compared favorably to sheep.

There is a temperamental resemblance in Freberg’s work to that of Mad magazine, with its critiques of advertising and media; to Tom Lehrer, another cheery satirist in song; in “Rocky & Bullwinkle,” with which Freberg shared voice artists June Foray and Paul Frees. In his commercial for “terribly adult” Cheerios, with actress Naomi Lewis, there is even an echo of the dry, modernist comedy of Mike Nichols and Elaine May:

“Well, I used to have these terrible headaches right here at the temple, and then I heard about Cheerios.”

Freberg (off-camera): “No, no — Cheerios are not a headache remedy.”

Lewis: “I’m sorry, I thought you were from a different company; I’ve been interviewed so much lately I just got confused.”

He was not immune from his own skeptical regard.

“Some legacy,” Freberg told Dick Cavett in a 1971 interview, mocking himself. “I’ve made the world safe for canned chow mein.”

It’s how he did it, of course, that mattered.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.