Head of money-losing L.A. County Fair Assn. made nearly $900,000 in total compensation

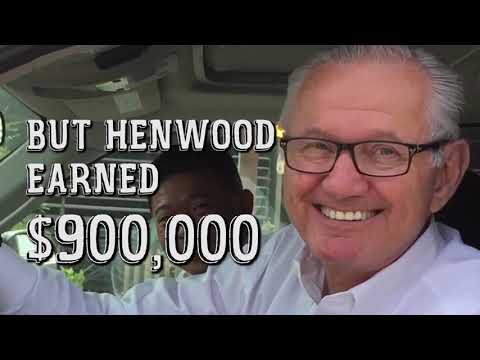

Los Angeles County Fair Assn. chief executive James Henwood Jr., right, listens to County Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, left, as they promote the annual event.

The Los Angeles County Fair Assn. was formed in 1940 to promote the region’s then-booming agriculture industry. For generations, the nonprofit organization’s annual fair crowned prize-winning hogs, taught children about crops and showcased thoroughbred racing.

But over the years, the association has morphed into something resembling a conglomerate, with little connection to farming or livestock. And its managers have become richly compensated even as the association loses money, a Times investigation has found.

The association controls a portfolio of enterprises that includes a hotel and conference center, a catering company and an equipment rental service. They are located on the county-owned fairgrounds in Pomona, sparing the association the obligation to pay property taxes. As a nonprofit, it also is exempt from taxes on most of its income.

Over the years, the Los Angeles County Fair Assn. has morphed into something resembling a conglomerate, with little connection to farming or livestock.

The organization has banked millions of dollars in government grants and received other support from taxpayers, according to its most recent federal tax filings. Despite the public subsidies, it lost a total of $6.25 million from 2010 through 2013 — though it rewarded its top executives with large bonuses and incentive pay in each of those years, the Internal Revenue Service records show.

The fair’s chief executive, James Henwood Jr., 69, collected nearly $900,000 in total compensation in 2013, dwarfing that of other fair managers in California, according to the tax filings and state records. That same year, the association lost $3.4 million.

From 2010 through 2013, Henwood and four members of his executive team received a combined $2.8 million in bonuses and incentive pay, boosting their total compensation to $8.75 million, according to the tax filings. In those four years, Henwood averaged about $846,000 in annual compensation.

“Running a fair is an executive position, and they should make some pretty good coin,” said Michael O’Hare, a UC Berkeley public-policy professor who has studied the economics and management of fairs. “But this sounds to me totally crazy.”

“Running a fair is an executive position, and they should make some pretty good coin. But this sounds to me totally crazy.”

— Michael O’Hare, UC Berkeley public-policy professor

As the association became more like a big business, it strayed further from its agrarian roots.

This shift came into stark focus in August, when the association booked a rave concert at the fairgrounds. Two young women who attended the rave were rushed to hospitals and died of apparent overdoses. The deaths prompted the association and concert promoter Live Nation to cancel another rave that was scheduled for September’s fair.

But a Halloween-themed rave Saturday and Sunday went on as scheduled. Police made more than 300 arrests, most for drug- and alcohol-related offenses.

A woman is arrested by California Highway Patrol officers at a security checkpoint for HARD Day of the Dead at the Pomona Fairplex on Oct. 31.

Unlike most major fairs in California, L.A. County’s is not run by a public agency. And although it works closely with county officials, the association has been free to compensate its executives as it sees fit and expand into other ventures.

In 2013, Henwood received more in bonuses and incentive pay than the association paid to the county for year-round use of the public fairgrounds, known as the Fairplex. A lease deal gives the association control of the nearly 500 acres in exchange for small shares of some of its revenues, such as 1.5% of the money generated by the fair and 5% of receipts from certain other events.

O’Hare and other experts say the association’s current operations could jeopardize its tax exemption under IRS rules, especially because so little of the organization’s business has to do with agriculture.

“It’s so removed from agricultural pursuits that it calls into question whether it qualifies for a tax exemption,” said Marcus Owens, a Washington attorney who once headed the IRS division on exempt organizations.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

The association’s 244-room Sheraton Hotel and conference center are on county land, along with a number of for-profit companies it owns, including the Cornucopia catering firm that serves food at the fair and events such as the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival in Indio.

“This isn’t what you think of when you think of charity,” said Rep. Norma Torres (D-Pomona), whose district includes the fairgrounds. “The government lands and subsidies are being used for the benefits of a few well-paid executives.”

Torres said the raves are an example of how the association has lost its way.

“How many more liquor-licensed events is it going to run?” she said.

Henwood and the other managers declined to be interviewed.

In an email to The Times, association spokeswoman Renee Hernandez said the organization has embraced the “evolution” of Southern California agriculture, as represented by competitions for wine, craft beer, extra virgin olive oil and dairy products. She said the association has increased the number and variety of animals at the fair, although she did not provide details.

As a private nonprofit, the association is not subject to direct oversight by the Board of Supervisors or any other public body. It is governed by an 11-member board of directors. The panel is elected by the 60 voting members of the association, according to its media guide. The members, in turn, are selected by the board, whose president is former Cal Poly Pomona President J. Michael Ortiz.

In a telephone interview, Ortiz defended the fair executives’ compensation, saying their pay was based on performance. He singled out Henwood’s supervision of the construction of the conference center, which opened in 2012. Ortiz said the center has done well financially. Henwood, a former shopping mall manager from Orange County, has led the association for two decades.

Ortiz said Henwood has excelled at managing the association’s Learning Centers programs. They provided vocational training to more than 600 students last year in auto mechanics, landscaping and other skills, according to the association’s annual report.

“We are training individuals in those areas to go out and do well in those fields,” Ortiz said.

Asked why Henwood and his management staff were handed bonuses in years the association lost money, Ortiz said, “I don’t think we have to explain.” He declined to answer further questions and ended the interview.

Other board members did not respond to interview requests or declined to comment. They include local corporate executives, developers, an accountant and a fitness club owner, as well as Robert Dukes, an L.A. County Superior Court judge in Pomona, and University of the West President Stephen Morgan.

Some fairgrounds neighbors have called for a ban on the raves and restrictions on the number of other events, which they say bring noise, traffic and crime. Like Torres, the residents, who have formed a group called Protect Our Neighborhood, contend the association is a nonprofit in name only.

“They present themselves as people who run county fairs, where you milk cows and the kiddies can pet animals,” said Jose M. Vadi, 71, a retired political science professor at Cal Poly Pomona. “Really, what they’re doing is they’re running a for-profit operation under the guise of being a nonprofit.”

The association describes itself as “self-supporting,” but it has turned to the government for financial assistance. Five years ago, the county issued $24 million in tax-exempt bonds that enabled the association to build the $28-million conference center at a reduced borrowing cost.

To help offset the cost of the center, the county gives the organization a discount on rent for the fairgrounds. The arrangement slashed the annual rent to an average of $200,000 from about $1 million in 2007.

County officials approved the rent rollback — it runs through 2022 — because they said the center would produce jobs and generate other “economic, social and public benefits.” In 2009, as part of a finance agreement with Pomona, the association estimated the center would produce 280 full-time jobs.

Hernandez, the association spokeswoman, did not respond to a question about the number of jobs actually created. Based at the fairgrounds, the association employs more than 250 people year-round, not counting workers at the hotel, Cornucopia and other businesses, its media guide says. According to the guide, the hotel employs 115 people; no number is given for the conference center.

County Supervisor Hilda Solis, whose district includes the fairgrounds, declined to be interviewed about the association.

Hernandez said in an email that the county gets money from a tax that promoters pay to use the fairgrounds. She said the county also benefits from an agreement with the association that allows the Sheriff’s Department to base its Emergency Vehicle Operations Center at the fairgrounds’ motor racetrack. The center trains deputies to drive patrol cars and motorcycles.

“The use of the facility for EVOC is a much higher value than any property tax that would have been derived,” Hernandez wrote.

The Sheriff’s Department, however, has said that it does not get enough access to the fairgrounds because of the fair and other events held on the property. As a result, the Board of Supervisors has tentatively approved a plan to build a $10.5-million EVOC in Castaic.

A spokesman for the county assessor’s office said the type of levy promoters pay at the fairgrounds — known as a possessory interest tax — often is significantly less than what property taxes would be for a similar property that is privately owned. Hernandez did not respond to a query of whether the association believes the county gets as much money from the fairgrounds as it would if it were taxed as private property.

Attendance at the fair has been seesawing. Once the largest county fair in the nation — it debuted in 1922, 18 years before the association was formed — the L.A. County event is now not even the biggest in California. It drew 1.2 million visitors last year, down from 1.49 million in 2011, state figures show. It reported 1.28 million visitors for this year’s fair, which was four days shorter than 2014’s.

According to the most recent tax records, the association was last in the black in 2009, when it had a net gain of $632,000 on revenue of $64.7 million.

It has reported different numbers to the state Department of Food and Agriculture, which collects financial information from most California fairs. In 2013, the association’s filing with the department showed a gain of $4.2 million; on its IRS return, it reported a $3.4-million loss.

The reason for the gap in figures was not clear, and state officials said they did not know why the numbers varied so much. The experts on nonprofits said a possible explanation is that the state and federal reports might follow different accounting rules.

In recent years, other leading fairs have performed better financially than L.A. County’s, according to state and county records. The San Diego County Fair brought in about as much total revenue in 2013, $66 million, as L.A. County’s, at $68 million, and has long been profitable, according to state records. Timothy Fennell, CEO of the Del Mar Fairgrounds, where the San Diego County Fair is held, had a salary-and-benefit package that year of about $184,000, roughly a fifth of Henwood’s compensation. The other four executives for the L.A. association also made more than Fennell.

Like the fair in San Diego County, Orange County’s event drew more visitors than L.A. County’s this year and in 2014. The Orange County Fair regularly posts a profit, state records show. Its CEO made about $212,000 in 2014. Both the San Diego County and Orange County fairs are run by state agencies.

Given the experiences of the other counties, experts say, it is difficult to see the benefit to L.A. County taxpayers in having the association, instead of the government, operate their fair. When government turns over management functions to private entities, they said, the public is supposed to get more for its money.

“There should be efficiencies,” said Rob Reich, co-director of Stanford University’s Center on Philanthropy & Civil Society. “But it sounds like there is no evidence here that there are any.”

“This has public subsidies of various kinds,” Reich said of the association. “It gives all citizens an interest in the healthy management of the entity.”

Because it is a nonprofit, the association does not produce earnings for investors, but it is expected to be fiscally sound and avoid losses, Reich said.

The association obtained its nonprofit status under the IRS code that exempts labor unions and certain agricultural organizations from taxes. Such an organization “must have as its primary purpose the betterment of the conditions of those engaged in agricultural pursuits,” an IRS publication states.

“Activities that only remotely promote the interests of those engaged in agricultural pursuits will not qualify an organization for exemption.”

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

The experts say the association’s nonagricultural businesses push the boundaries of its tax exemption. In 2013, it reported to the IRS about $25.6 million in total business revenue from the hotel and conference center, Cornucopia and other firms — taxable receipts unrelated to its nonprofit purposes to advance agriculture. The business proceeds were about equal to the association’s revenue from the fair.

“The fact that the organization is operating a hotel 24/7, 365 days a year, that pattern is suggestive of an organization that is no longer being operated to further agriculture,” said Owens, the former IRS official.

O’Hare, the Berkeley professor, said the association’s exemption gives it a leg up over marketplace competitors that do pay taxes, such as nearby hotels and music venues.

“It’s unfair to merchants who do not get the same tax exemption,” O’Hare said.

Mario Ramos, 53, a member of Protect Our Neighborhood, agreed, saying the association functions like “a monopoly that’s being subsidized by the government,” squeezing out local businesses.

“I make the argument that it actually hurts us by them being there,” said Ramos, a healthcare consultant.

The fair has stopped inviting the young people who belong to 4-H clubs to display their animals. The thoroughbred meets — once a staple of the event — have been moved to the Los Alamitos racetrack in Orange County.

Association spokeswoman Hernandez said the organization has expanded the acreage and programming dedicated to agriculture, including through classes at the Learning Centers. She did not respond to requests for information on how much it spends on those programs.

Hernandez said the association eliminated 4-H clubs from the fair because fewer children were showing their animals.

The fair’s website says the event has gone “back to our agricultural roots.” There were pens of cows, pigs and chickens at this year’s fair, along with a petting zoo, a milking demonstration and an “urban garden” of fruit trees and vegetable patches, which is open throughout the year.

But most of the fair remained devoted to carnival rides, market pavilions for a constellation of nonfarm products — including hoodies, hot tubs, e-cigarettes and toe rings — and a concert series that featured ZZ Top and Patti LaBelle.

Joanne Kissling, 61, of Agoura Hills, said she and other 4-H leaders were stunned when the L.A. County Fair booted the clubs’ animals.

Joanne Kissling, 61, of Agoura Hills, said she and other 4-H leaders were stunned several years ago when the fair booted the clubs’ animals. The 4-H exhibits are still welcome at other fairs, including Orange County’s and San Diego County’s.

“We were there one year, and we were gone the next,” Kissling said of the L.A. County Fair, where her daughters used to present their goats, rabbits and guinea pigs.

“They don’t really have what I consider a fair. A fair to me means the animals.”

ron.lin@latimes.com | Twitter: @ronlin

paul.pringle@latimes.com | Twitter: @PringleLATimes

richard.winton@latimes.com | Twitter: @Lacrimes

ALSO

L.A. City Council to weigh proposals to slash parking fines

Ex-L.A. County sheriff’s sergeant sentenced to 8 years in prison in jail visitor beating

Lamb sacrifice performed for man 5 days before he was ejected onto freeway sign

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.