Off the streets and into the OR: a new UCLA doctor turns his life around

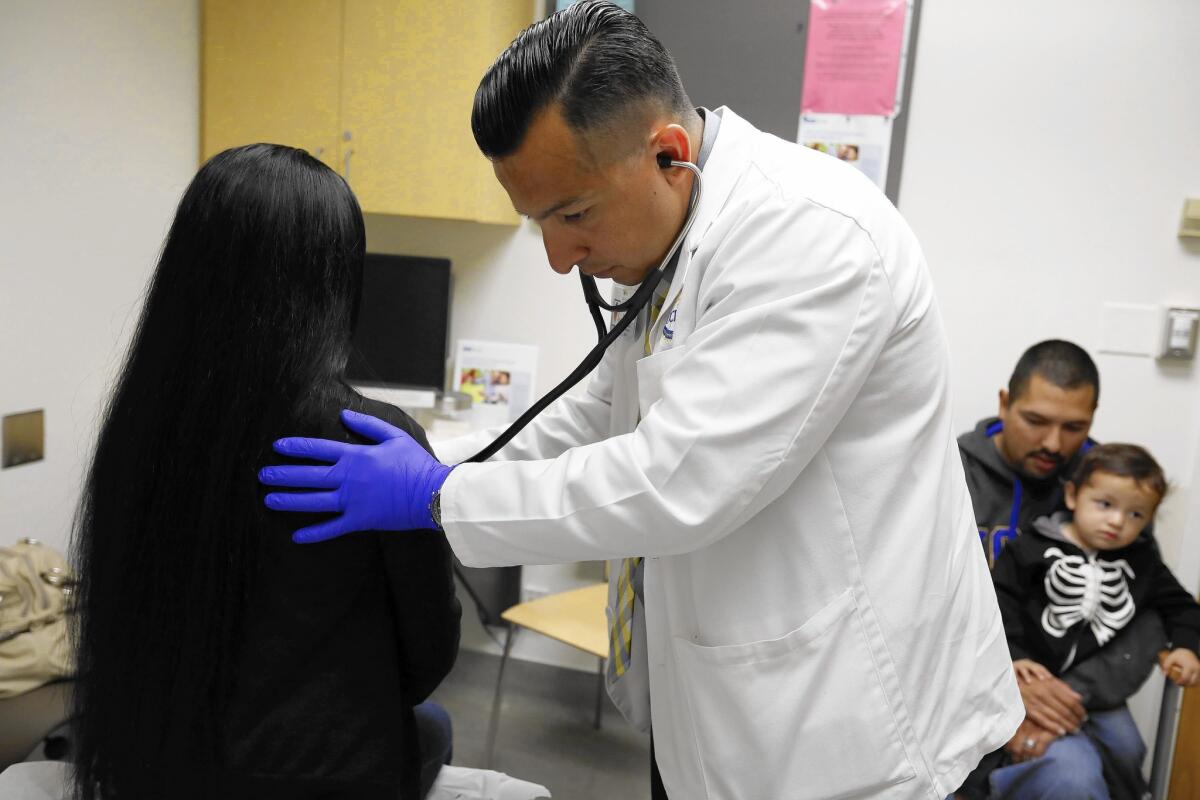

Dr. James Maciel examines patient Aurora Franco as her son Jonathan and Husband Hector wait.

Two very different documents define James Maciel’s unusual life journey.

The older one is a photocopy of his court records from the late ‘90s, showing arrests for graffiti vandalism and possession of a handgun that landed him in Orange County Juvenile Hall and the Youth Guidance Center for six months. It is an unhappy souvenir of a teenage phase that could have led to hard-core gang life and all its dangers, he said recently.

The other document is his new UCLA medical diploma, earned at the relatively late age of 33 while he and his wife were raising their three children. The diploma is a passport to Maciel’s upcoming residency in surgery at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, the Carson hospital that serves many low-income people and immigrants and is among the busiest in the state in treating gunshot wounds.

“The people I lived with and grew up with are the people I want to take care of. The indigent and the gang members,” Maciel, who grew up in Santa Ana and now lives in Garden Grove, said in an interview. “It’s just a natural fit for me.”

To successfully complete medical school at that age, with children, is unusual, and to do it after such adolescent troubles is “distinctly rare,” said Christian de Virgilio, a professor of surgery at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine and interim chair of surgery at Harbor-UCLA.

He said that Maciel has been a mature role model for younger medical students and has shown special interest in and compassion for victims of violence and other trauma. He cited a study published recently in the Annals of Vascular Surgery, for which Maciel was the lead author, about how massive transfusions help gunshot and car accident victims survive devastating injuries to their abdominal aorta.

Maciel credits much of his success to his wife, Priscilla, with whom he had their first child when he was 18 and she was 17. She later got him to leave his tagging crew. His embrace of a strong Christian faith helped as well, he said. He also acknowledges mentors at Orange Coast College, where he rediscovered a love of science; UC Irvine, where he earned a bachelor’s in biology; and UCLA’s med school.

Asked about advising teens in detention today, Maciel said he would tell them: “I was just like you. I know what you are going through. I know you think you’ve made mistakes that are irreparable and unforgivable. But you need to realize you are your own worst enemy by your own self-doubt and believing people who tell you that you are going up to end up dead or homeless, or in jail or crazy or on drugs. You have to realize there is a way out.”

The son of Mexican immigrants, Maciel was initially a good student, attending a program for the gifted. But at Saddleback High School in Santa Ana, he fell in with a tagging crew, was repeatedly busted for graffiti and placed in court-ordered cleanup groups. He was expelled from two schools and dropped out of a third. The 1998 handgun possession charge, documented in papers he still has, led to the 180-day detention; he said he never fired the gun at anyone or used it to threaten anyone.

An old photo, he notes with chagrin, shows him wearing the detention uniform but in a gangbanger pose, chest pumped out and a smirk on his face. Maciel declined to disclose his tagger name, saying “that person doesn’t exist anymore.”

Mona Ruiz, a now-retired Santa Ana police detective who ran an anti-graffiti and gang diversion program, recalled Maciel as “a sharp and very outgoing kid” who skirted more serious trouble. She described him as a tagger, not a hard-core gangbanger, who “liked pushing the limit as long as he didn’t get caught.”

She lost contact with him after he was sent to detention but said she was delighted to learn from a Times reporter about his medical career. “I’m always happy when I hear that a juvie who was in our program picks himself up and is successful,” she said, adding that Maciel might have followed other teens who died in shootings and drug overdoses.

While in the lockup facilities, Maciel realized that “I was getting tired of getting in trouble, and I was causing a lot of pain to people.” After his release, he earned his high school degree at an alternative school and got a job at a sign-painting factory where his father worked. Fatherhood pushed him to think about his future, and his parents provided a role model for hard work, he said. A few years later, while working as a school custodian, he enrolled in community college, as did his wife.

That began a long dozen years of higher education, with financial help from family, government assistance programs, scholarships, student loans and part-time jobs.

After UC Irvine, Maciel was accepted by the UCLA medical school’s PRIME program, which recruits future doctors to work with underserved and low-income communities. The program adds a fifth year by requiring students to also earn a related master’s degree — in public health in Maciel’s case.

(Med school runs in the family. Maciel’s older brother attended medical school in Mexico, although he does not practice in the U.S. A younger brother is in the class behind Maciel at UCLA’s medical school.)

PRIME Executive Director Lawrence “Hy” Doyle said Maciel was chosen for one of 18 slots from 850 applicants in part because “what intrigued us was that he was able to overcome so much.” Maciel’s family responsibilities also gave him “a focus in a way that many other medical students don’t have,” Doyle said.

As part of his UCLA hospital duties, Maciel recently examined a woman in her early 30s who described abdominal pain that she thought might be related to the unusual placement of some internal organs since birth. With the woman’s husband and infant son in the exam room, Maciel took her history to pass on to senior physicians and made sure she did not need emergency care.

On his way out, he urged the couple to contact him if their older children had questions about applying to college or studying medicine. The couple, Aurora and Hector Franco of El Monte, said they appreciated the extra attention.

The next day, about 35 friends and relatives, including Maciel’s two sons, 15 and 14, and daughter, 6, attended his graduation and a celebratory dinner at a Westwood seafood restaurant. Priscilla, who earned her bachelor’s degree at Cal State Fullerton and works as a benefits eligibility technician, said the couple’s early life together now “seems like a different story about different people.”

While it was hard to keep the end goals in sight, they tried to “stay focused” through the difficult juggling of education and parenthood, she said.

Now their sons want to become doctors. “I tell them to go for whatever it is they want to do,” she said.

Twitter: @larrygordonlat

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.