In booming marketplace for Cuban players, Puig’s tale far from unique

Yasiel Puig’s journey to Los Angeles — and riches with the Dodgers — is a serpentine tale of drug cartels, nighttime escapes and international human smuggling.

Yet in the booming marketplace for Cuban ballplayers, it is far from unique.

Since 2009, nearly three dozen have defected, with at least 25 of them signing contracts worth more than a combined $315 million.

Many, like Puig, were spirited away on speedboats to Mexico, Haiti or the Dominican Republic. Once there, they typically were held by traffickers before being released to agents — for a price.

FOR THE RECORD:

This article misspells the name of Puig’s original agent, Jaime Torres, as Jamie.

Puig’s case drew widespread attention after Los Angeles magazine and ESPN the Magazine published articles this month detailing the gifted young outfielder’s harrowing trek to the United States.

That spotlight aside, the smuggling of Cuban players has been the subject of federal investigations for years, resulting in a handful of prosecutions.

Still, the flood of risky defections has continued.

Over the last six months, the Department of Homeland Security has been working on at least two separate cases involving smuggling rings that brought baseball players out of Cuba into the United States, said a former federal law enforcement official with knowledge of the matter.

The pattern has been for smugglers to force players to sign agreements stipulating they will turn over a percentage of any initial contract signed with a big league club — often more than 20%.

The players are viewed as victims and were not under investigation themselves, the former official said. Investigators said they had spoken with Major League Baseball officials about the probes and presented them with a list of players who were being extorted.

Some, authorities said, still are making payments to smugglers. And some of their families in Cuba still are threatened with violence.

Nestor Yglesias, a spokesman for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in Miami, would not comment on whether agents were looking into the Puig smuggling case.

But a long-running investigation by Homeland Security Investigations and the FBI resulted in the indictment late last year of a trio of Cuban nationals for the alleged smuggling of as many as a dozen players, including current Texas Rangers outfielder Leonys Martin.

Even as U.S. authorities are trying to stop the smuggling, the prospect for multimillion-dollar major league contracts remains a powerful lure for Cuban players — and those willing to bring them here.

“Ten years ago a player would leave Cuba, sign a nice contract, and people in Cuba might kind of hear rumors about how well he’s doing,” said Joe Kehoskie, a former player agent.

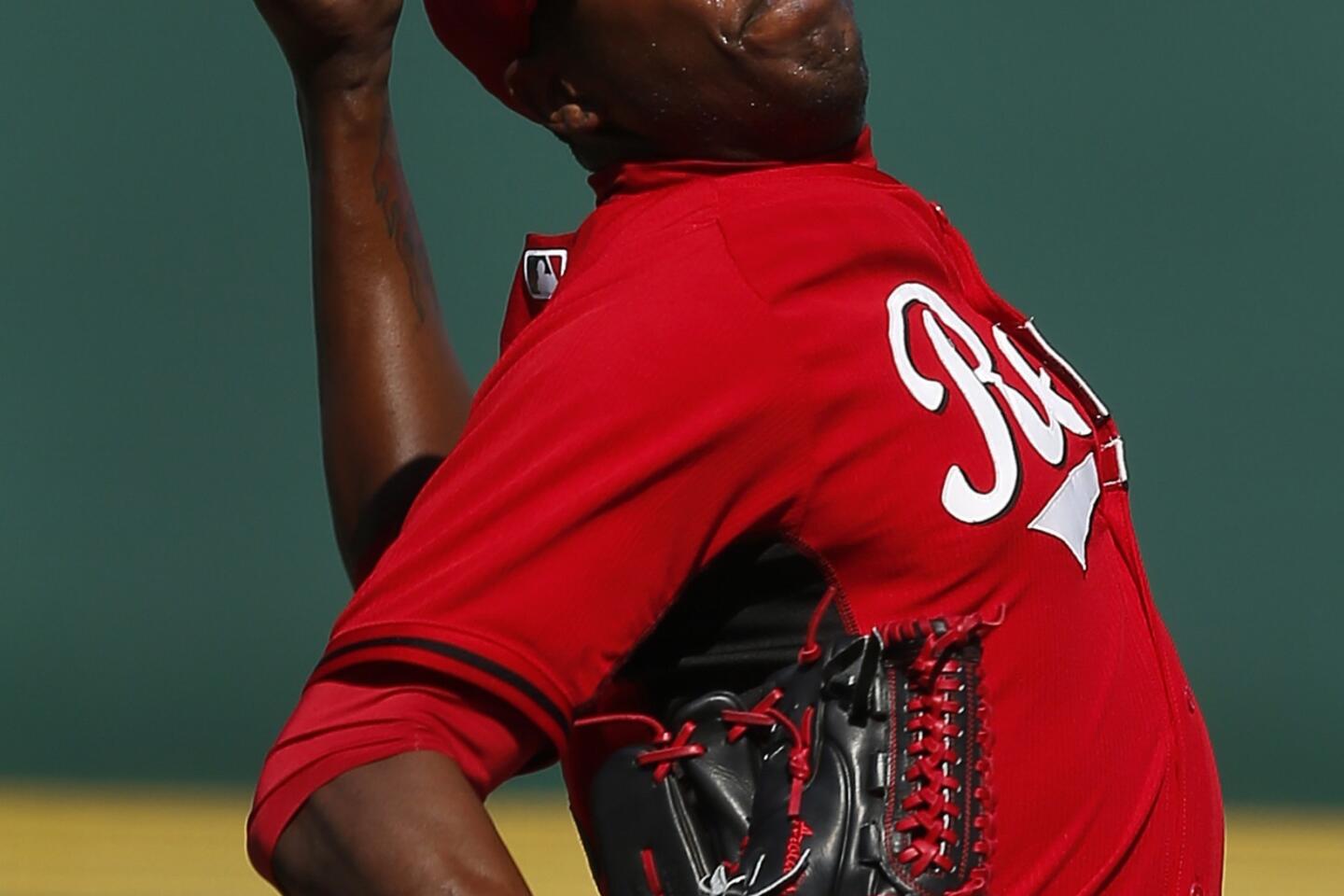

Now, he said, pointing to Cincinnati Reds pitcher Aroldis Chapman — who defected in 2009 during a tournament in the Netherlands and signed a six-year, $30.25-million contract —”Chapman’s Lamborghini is on Facebook. Chapman’s mansion is on Facebook.”

The trafficking is a result of the trade embargo with Cuba, which prevents any economic assistance to people on the island, and Cuba’s unwillingness to allow its players to sign with major league teams.

Thus, prospects have to either defect on their own or enlist smugglers to take them to the United States or another country.

Florida was originally the favored route, but increased monitoring by the Coast Guard has made the voyage riskier. In addition, by establishing residency in another country, Cuban players are not subject to Major League Baseball’s domestic draft, allowing them to sign as free agents.

Puig was smuggled out of Cuba on a speedboat in June 2012 along with three others, including a boxer and childhood friend named Yunior Despaigne, according to records in a lawsuit filed against Puig. (He is being sued for $12 million by a man in Cuba who claims Puig made false allegations that landed him in prison.)

Despaigne said in the affidavit that the group was ferried to the tip of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, some 300 miles away. The smugglers were associated with a Mexican drug cartel, which allowed them to bring their human cargo ashore and helped with security and other details, according to the magazine accounts.

Puig’s escape was arranged and partly financed by a Miami man named Raul Pacheco, according to an affidavit by Despaigne in the lawsuit. Once Puig was in Mexico, the smugglers demanded more than the $250,000 Pacheco had agreed to pay for his release, according to Despaigne’s sworn statement.

When Pacheco balked, they threatened to harm Puig in a way that would end his career, according to the Los Angeles magazine account.

After nearly a month, Pacheco and some Miami partners hired several men to free Puig and the others from their hotel and get them to Mexico City, the affidavit states.

Puig’s agent at the time, Jamie Torres, negotiated a stunning seven-year, $42-million contract with the Dodgers.

Cuban players began to appear in the U.S. in the early 1990s, slipping away during national team visits for tournaments. Later, smugglers routed players through Florida and Mexico, according to testimony in 2012 from Special Agent Thomas Roberts of ICE’s Homeland Security Investigations.

The agent said smugglers usually charged $10,000 to get someone out of Cuba, but up to 25 times that for ballplayers — not including the portion of future earnings many athletes must pay.

In recent years, many Cuban players’ contracts have hit stratospheric levels.

Yoenis Cespedes signed a four-year, $36-million deal with the Oakland Athletics in 2012, just months before the Dodgers gave Puig his deal. That record was broken five months later, when the Chicago White Sox signed Jose Abreu for $68 million over six years.

Last week, legislation was introduced in Florida to pressure Major League Baseball into changing its rules on Cuban players.

Florida Reps. Jose Felix Diaz and Matt Gaetz proposed a measure requiring the Miami Marlins and Tampa Bay Rays to demand that baseball treat Cuban players as it does other foreign players — as free agents, so they wouldn’t have to travel to Mexico or another country.

“Major League Baseball’s rule punishes Cuban ballplayers by forcing them into the arms of human traffickers,” Gaetz said. “The taxpayers of Florida should no longer subsidize human smuggling.”

For more than a decade, some have called for an international draft that would make every amateur player subject to the same negotiating rules as American prospects. But baseball has been unable to reach such an agreement with its players union.

“The current problem is partly of MLB’s creating, but MLB faces a Catch-22 in trying to address it,” said Kehoskie, the former agent. “Many of the things MLB could do to disincentivize the smuggling on the front end, such as implementing a worldwide draft … would hurt Cuban players on the back end by causing them to sign much smaller contracts.”

Baseball Commissioner Bud Selig, asked Friday about the dangers confronting Cuban ballplayers trying to defect, said, “Do I have concerns? Yes, of course I have concerns. The more I read, the more I hear.”

Rob Manfred, MLB’s chief operating officer, said baseball officials are discussing possible changes in international signing rules with the players’ association. “Over the long haul,” he added, “what I’d say is that it is a problem that is larger than baseball.”

Major League Baseball’s responsibility in stopping player smuggling is complicated by the geopolitics of the Cuban situation.

At the least, baseball should try to determine if agents representing Cuban players have been involved with smuggling operations or engaged in extortion or other criminal activity, said Shawn Klein, a philosophy professor at Rockford University in Illinois who writes the Sports Ethicist blog.

Mike Gilleran, executive director of the Santa Clara University Institute of Sports Law and Ethics, said Major League Baseball is “well past the point of saying, ‘Gosh, this is shocking,’” when stories such as Puig’s make headlines.

“It seems to me that there had to be so many sirens going off, so many red flags jumping out,” he said.

Still, he said, it’s not clear what baseball can do: It can’t dictate immigration policy, and there would be no point in rejecting ballplayers who have fled an oppressive regime for a better life.

Pretending the problem doesn’t exist is not an option, he said.

“I think reasonable people would look at it and say … ‘This is our labor force. These are our ambassadors.’ If we want baseball 100 years from now to be held in esteem, let’s do something.”

Times staff writers Joe Mozingo and Kim Christensen in Los Angeles, Mike James in New York and Richard Serrano in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.