Billionaire who barred access to Martin’s Beach takes stand

Silicon Valley venture capitalist Vinod Khosla took the stand Monday in a closely watched civil lawsuit that alleges the co-founder of Sun Microsystems improperly barred public access to a beloved San Mateo County beach in violation of the California Coastal Act.

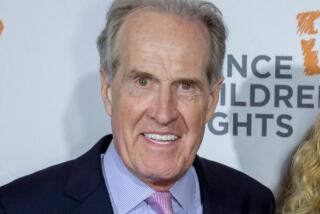

Repeatedly, the slender billionaire with the close-cropped helmet of white hair said he had “no recollection” of discussing the issue of beach access with his property manager outside the presence of his attorneys.

Khosla also said that he had no plans to bar the gate when he bought the property, and that he did not remember being told that he had effectively lost a lawsuit in 2009 in which he asserted that he did not need a permit to cut off public access to Martin’s Beach.

Instead, Khosla maintained that manager Steve Baugher was empowered to make all decisions about the property.

Khosla paid $37.5 million in 2008 for two parcels of coastal land and a road that residents had for decades used as the only way down to the white-sand cove south of Half Moon Bay.

The Surfrider Foundation has sued Khosla, contending that his actions (or those of his two limited liability companies) — barring the gate, painting over a billboard that had long welcomed the public and hiring security guards to fend off trespassers — changed the “intensity of use” of the beach and thus required a coastal development permit.

Attorneys for Khosla counter that the private property owner had had every right to lock his gate and bar the road that visitors had previously used by permission of the prior owner — and that the actions he took did not constitute “development” and so did not require a permit.

Joe Cotchett, outside counsel for Surfrider, conceded outside court Monday that it makes no legal difference whether Khosla was personally involved in the decisions. But he said he was “dumbfounded” by Khosla’s responses.

“He cannot seem to remember a thing,” Cotchett said.

The content of conversations Khosla had with his attorneys is protected, so he was not compelled to disclose the advice they gave him. But Khosla maintained that he could not recall what his thoughts were about the matter outside the presence of counsel.

Cotchett: “At any meeting with Mr. Baugher and your counsel when you discussed access, what was your understanding of public access when you left the meeting?”

Khosla: “I don’t recollect.”

Records show that San Mateo County officials had informed Baugher that the new owners must maintain the historic and affordable public access, and that plans for a change in intensity of use required a permit. Instead of seeking one, Kholsa sued the county and the Coastal Commission, which enforces the Coastal Act of 1976, contending that he was not legally required to comply.

A judge threw out the case, telling Khosla to go to the Coastal Commission and exhaust that administrative proceeding before turning to the courts.

In that ruling, San Mateo County Superior Court Judge John Grandsaert wrote that the plaintiff “concedes that the definition of ‘development’” in the law “includes a ‘change in the intensity of use of water, or of access thereto.’”

Khosla said he could not recall being told of the ruling by his counsel and only vaguely remembered the suit.

Khosla’s attorneys argue that he was not intentionally flouting the law but awaiting a legal challenge that would allow him to test it — and possibly set precedent for private property owners.

Surfrider contends that Khosla should face heavy fines because he was expressly told that he needed to seek a permit and did not do so.

“It was your intent to have someone come and file papers to get a judicial decision on public access,” Cotchett pressed Khosla on the stand.

“I don’t think I said that,” answered Khosla, dressed in a black corduroy jacket and hunched slightly on the stand. “My intent was to determine what the law says on this issue — not let public opinion determine the issue but to let facts of law determine the issue. That was my intent.”

Also Monday, attorneys for Surfrider called former state Sen. Jerry Smith, who helped pass the California Coastal Act, to explain its intent and requirements.

“One of the goals, of course, is maximizing — and that’s the word used — access for the public,” he testified.

On cross-examination from Khosla attorney Jeffrey Essner, Smith also said the act protects the interests of private property owners whose land abuts the coast.

“The balance of private property rights and the other goals of the Coastal Act was important, wasn’t it?” Essner asked.

“Yes,” Smith replied.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.