After guilty verdict, prosecutors seek to strip Mongols biker gang of trademarked logo

Federal prosecutors in California pressed ahead with a novel attempt to dismantle an outlaw motorcycle club, arguing to jurors that the group should be stripped of trademarks it owns on its coveted insignia as punishment for operating a criminal organization.

Last month, at the end of a lengthy trial, a jury in Santa Ana convicted the Mongols motorcycle club of racketeering and conspiracy charges, finding the group shared responsibility for several violent acts and drug crimes committed by individual Mongol members.

After the guilty verdict, U.S. District Judge David O. Carter had jurors return to court this week to make another decision: whether the club’s insignia is linked closely enough to the crimes to warrant forcing the Mongols to forfeit the group’s trademarks to the U.S. government.

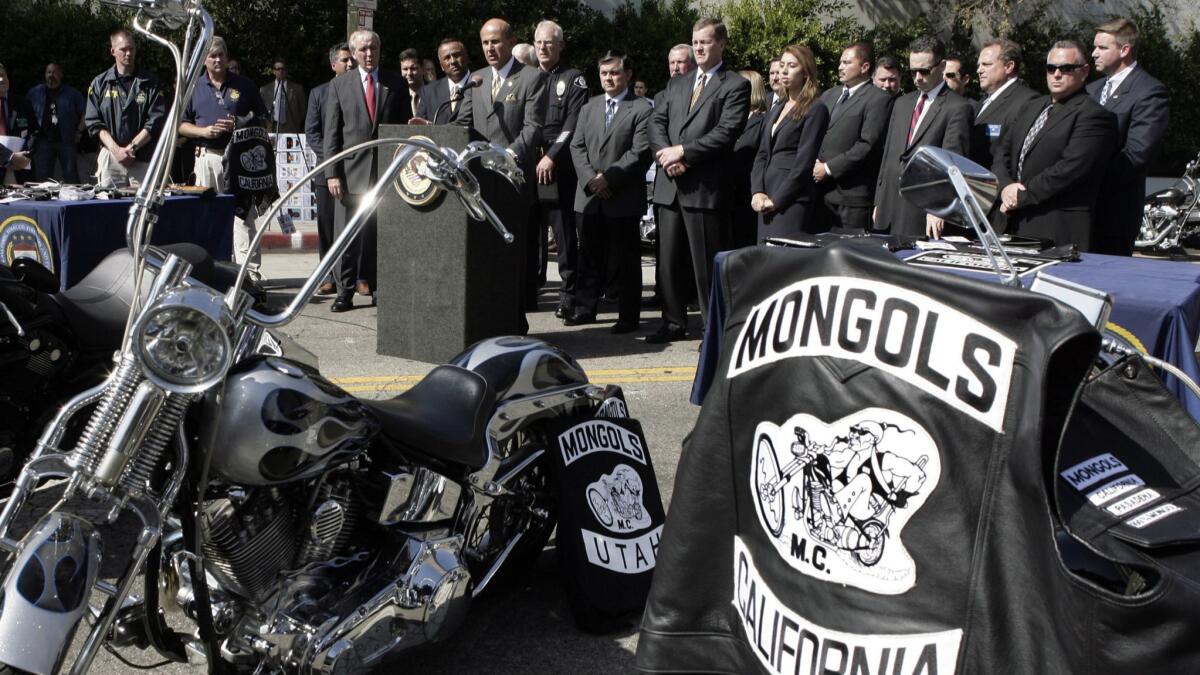

If there is one thing on which both sides in the case agree it is that the club’s trademarked logo — a Genghis Khan figure in sunglasses riding a motorcycle beneath the group’s name in large block letters — is the cornerstone of the Mongols’ identity. Only members are permitted to wear large patches of the insignia on the back of their riding vests — an unmistakable totem in the insular, hierarchical world of motorcycle clubs, in which full-fledged members lord their superiority over aspiring plebes and rival clubs often clash violently in turf battles.

Pictures in the News | Thursday Jan. 10, 2019 »

The government has been trying to wrest the trademarks away from the club for a decade — a strategy based on the idea that without the trademarks, Mongol leaders will be starved not only of the money members pay for patches and other merchandise, but also of the ability to control who wears the potent Mongol image.

It is a first-of-its-kind legal gambit and one trademark experts have questioned, saying they doubt whether the nation’s trademark laws will give the government any meaningful power to stop Mongol members from wearing the insignia.

The Mongols were formed in the 1970s in Montebello, outside Los Angeles, by a group of Latino men who reportedly had been rejected for membership by the Hells Angels motorcycle gang. It has expanded over the decades to include several hundred members who thrive on their identity as outlaws. Dozens of members have been convicted of an array of crimes, including the killings of rival biker gang members, assaults and drug dealing.

At Tuesday’s hearing, Joe Yanny, an attorney for the Mongols, tried to convince jurors that the bid for the trademarks was a dangerous overreach, saying the government was seeking “the death penalty” for the Mongols.

He argued that prosecutors had failed to show the insignia, which adorns T-shirts, rings, coffee mugs and other paraphernalia as well as the patches, had any connection to the club’s crimes and said forfeiting the trademarks would unfairly punish Mongol members who had done nothing wrong.

Yanny called a trademark attorney to testify about the minutiae of “collective membership marks” — the type of trademark the club received for the insignia — in an effort to bolster Yanny’s claim that the trademark belonged collectively to the Mongols’ individual members, rather than the organization and its officers.

Assistant U.S. Atty. Steve Welk countered with testimony from Darrin Kozlowski, a retired agent in the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives who posed as a biker to infiltrate the Mongols.

Kozlowski testified about the tight control that officers in the Mongols’ “mother chapter” in West Covina kept over use of their insignia and patches. For example, Kozlowski testified that when the Mongol chapter he joined wanted to design a T-shirt to sell at club gatherings, they first had to seek permission from the group’s top leaders.

In his closing statement, Welk hammered on the idea that the insignia and the patches worn proudly by members were inseparable from the Mongols’ identity and, by extension, the club’s crimes.

He urged jurors to think of Mongol members as “men … empowered by these symbols that they wear like armor, roaming the world like urban predators, searching for people to victimize.”

The jury began deliberating Wednesday, but its decision is unlikely to be the final word in the case.

In court filings, Yanny said he expected he and others would mount constitutional challenges to any forfeiture order, saying Mongol members’ 1st Amendment right to express themselves and associate as a group would be violated.

Twitter: @joelrubin

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.