‘There’s nothing wrong with being white.’ Trump’s win brings ‘white pride’ out of the shadows

As he watched the news of the presidential election in the last week, Kory Duquette became increasingly agitated. Pundits were blaming a “whitelash” for Donald Trump’s win and called it a massive exercise of angry white ballot power.

Civil rights groups said the president-elect’s victory has inspired dozens of attacks on blacks, Latinos and Muslims by people who shared Trump’s suspicions about immigrants. Commentators said that in his quest for a win, Trump pandered to America’s darkest racist impulses.

Duquette, a Trump supporter from Alabama, was ready to fight back.

“#Whiteshaming doesn’t work anymore! you label me? you wonder why Trump won?” Duquette, who is white, posted this week on Twitter. “Tired of being classified with untruths.”

Duquette voted for President Obama eight years ago and would never call himself a racist. Like many Americans, he was sold on Trump’s promises to create jobs and fight terrorism. But there was also something else that attracted him.

Trump has eliminated “that uncomfortable feeling of being afraid to speak your mind as a white man,” said the 37-year-old prison guard. “There is nothing wrong with being white.”

Much has been said about the rise of white nationalists who have felt emboldened by Trump and his association with people and groups known to espouse anti-Muslim and anti-Semitic views.

One of the more widespread effects of the Nov. 8 election may be the emergence of a broad array of everyday Americans who insist they’re not white nationalists but say the president-elect has made them more comfortable in their white skin.

In an era of dueling “black lives matter” and “all lives matter” campaigns and regular debates over free speech and political correctness, Duquette, who says he has heard the phrase “white privilege” one too many times, said he now feels vindicated.

“We were, I felt, backed into a corner and … told, ‘You white people had your day, it’s our turn now,’” he said this week from his home in Arab, Ala. “I feel Trump broke that P.C. barrier, … made me feel comfortable again to speak out.”

Trump’s election has thrust race even more squarely into the simmering national debate over justice and American identity.

Protesters have blocked streets in dozens of cities over a vote they see as affirming racism and xenophobia.

There has been widespread alarm over a wave of hate incidents directed at minorities across the country, the largest number seen since the period after Obama’s election, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. Some Trump supporters have been beaten in public as well.

This week, the mayor of Clay, W.Va., resigned after praising a friend’s Facebook comment that called First Lady Michelle Obama an “ape in heels” and celebrated her imminent departure from the White House.

In Wellsville, N.Y., graffiti was painted on a dugout wall featuring a swastika and the words, “Make America White Again.”

At a Starbucks in Miami, a white customer began yelling, “Trump! Trump” at a black barista, declaring he was the victim of “white discrimination.”

At New York University, students found Trump’s name written on the door to a Muslim prayer room on campus.

The Ku Klux Klan announced it would hold a Trump victory parade in North Carolina next month.

One of the catalysts for controversy has been Trump’s naming of Breitbart News executive chairman, Stephen K. Bannon, as a senior advisor. Bannon once called his website the “platform of the alt-right,” a movement broadly associated with white nationalism.

He has been accused of making anti-Asian and anti-Semitic remarks, and both critics and supporters say his influence will allow his self-described “virulently anti-establishment” ideas about women, gays and others to permeate the next U.S. administration.

Since the election, Bannon has said he doesn’t agree with “ethno-nationalist” parts of the alt-right, though critics say that such views are a central part of the movement.

Already, there are signs that many of those on the fringes of U.S. conservatism are angling to position themselves closer to the centers of power.

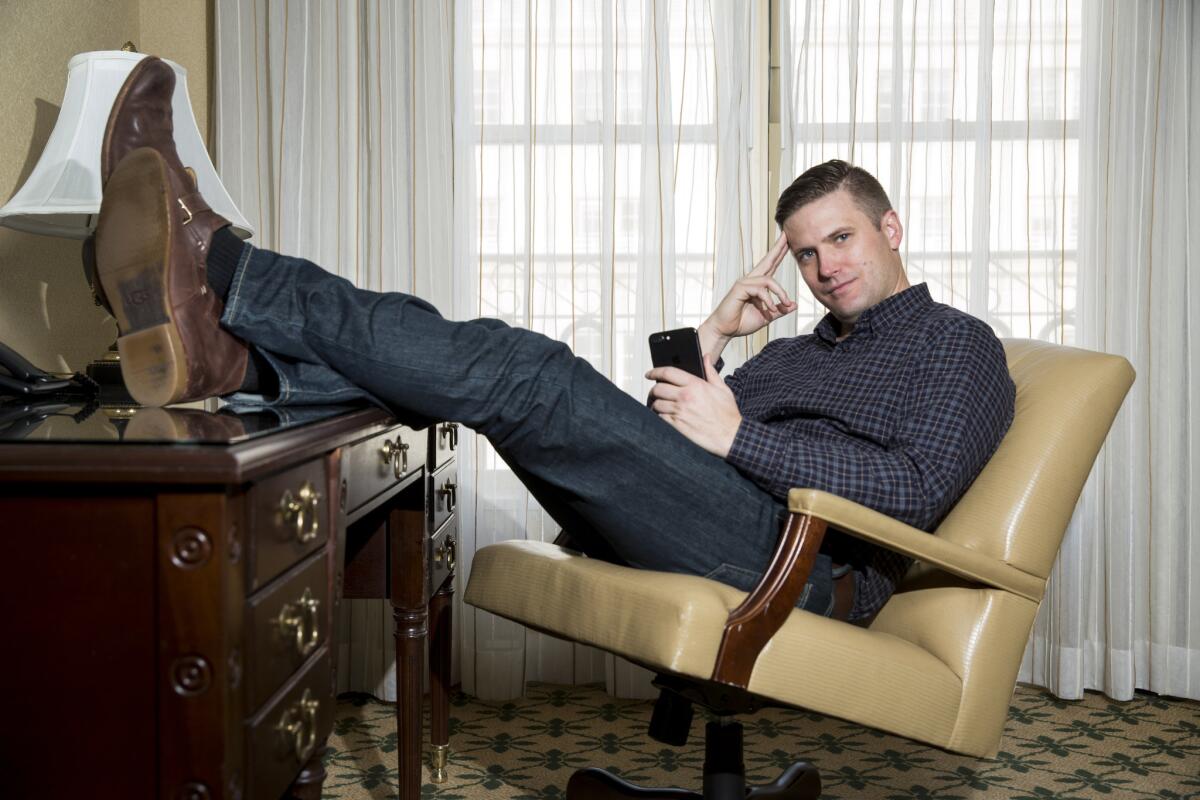

Richard Spencer, the chairman of a small alt-right policy institute in Montana who has spoken about “peaceful ethnic cleansing” and a “proxy war” on immigration, is now scouting for office space in Washington.

Trump’s win “was white Americans of all classes revolting against political correctness,” said Spencer, whose National Policy Institute has been described by the Anti-Defamation League and Southern Poverty Law Center as a white nationalist hate group.

Whites are “expressing a desire for identity politics, or at least the beginning of it,” he said.

Spencer has long argued that politicians and the media have falsely convinced whites they should feel “guilty” while encouraging racial pride among blacks, Asians and Latinos.

Few listened. Then Donald Trump began to rise.

“There is no way he doesn’t know of us,” said Spencer, whose group, now housed in home offices, plans to host a conference Saturday at the Ronald Reagan Building in Washington.

Already, there is push-back. On Wednesday, Twitter suspended five accounts that Spencer used — with about 100,000 followers in total — as well as those of dozens of other alt-right handles.

Still, variations on alt-right ideas are capturing attention.

“We’re coming to the realization that white self-hatred is a sickness,” said Timothy Murdock, a 46-year-old alt-right podcaster from Dearborn, Mich. He said he considers himself “pro-white,” but feels the alt-right movement could get better traction by going to battle against “diversity.”

“There is great attention to the term ‘diversity,’ that it means ‘too white,’ coupled with open borders,” said Murdock, whose podcasts frequently talk about “white genocide.”

Sociologists and hate speech experts say white nationalism and white identity politics are different and don’t necessarily bleed into each other; instead, they fall on a spectrum.

Some of today’s debates hark back to lawsuits and protests in previous years over such issues as university affirmative action admissions policies. Even then, many Americans were arguing that whites had suffered under policies meant to correct long-standing racial disparities.

No one in those cases was advocating a return to segregation, said Thomas Maine, a professor at the City University of New York who is writing a book on the alt-right movement.

“The alt-right has a hardcore, and then it has a population manifestation,” said Maine. “People have embraced the idea that Americans need to take hold of their racial identity. If we do that, if we are more radical about it than we have been before, this will bring us out of our funk.”

Duquette, the Alabama corrections officer, said he could support that idea.

“I should be out and be able to say I’m a proud white man,” he said. “But those lowlifes that have taken ahold of that phrase like the Klan have it so we have to walk on eggshells.”

Christine Bolan, a 35-year-old construction project manager in St. Paul, Minn., said there is “a lot of misunderstanding about what Trump’s message actually is.”

He is “brash but gives everyone a chance,” she said. He “doesn’t put labels on people” and “is a businessman.”

On the one hand, Bolan, who is white, thought it was “really cool” to have a black president. But in the end, she thought “Obama cared more about black people.” Democratic politicians have too often tried to make her “ashamed to be white,” she said.

Mark Potok, a civil rights activist who tracks hate groups for the Southern Poverty Law Center, said the election has “emboldened” the radical right.

“Virtually every major white supremacist leader in the U.S. thinks Trump is the best thing they have seen in more than half a century. They’re calling him ‘our glorious leader,’” said Potok. “They feel Trump and the Trump campaign have legitimized their concerns and brought them into the mainstream. And they are not entirely wrong.”

Jaweed Kaleem is The Times’ national race and justice correspondent. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

ALSO

White nationalists’ ‘man in the White House’? Bannon appointment provokes angry rebukes

Trump supporters try to undermine Megyn Kelly’s book with an onslaught of negative reviews on Amazon

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.