A dark day for the game

In a blow to the reputations of baseball legends, journeymen players, team owners and union representatives, an investigative report on drug use in the major leagues released Thursday by former U.S. Sen. George Mitchell blasted America’s pastime for its slow and ineffective response to what it called “baseball’s steroid era.”

The 409-page report released here amid great fanfare and serial news conferences cited performance-enhancing drugs as a widespread problem that involved players from each of the 30 teams in both the National and American Leagues.

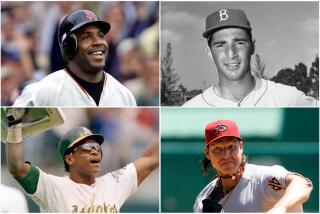

Mitchell named 86 current and former professional players as drug users, saying they ranged from those “whose major league careers were brief to potential members of the Baseball Hall of Fame.” But it was that group of big names that turned Mitchell’s report into an instant sensation and one of the biggest scandals in modern U.S. sports.

Among the report’s disclosures were:

Seven-time Cy Young Award-winning pitcher Roger Clemens repeatedly used steroids and human growth hormone, injected by his conditioning coach. The same conditioning coach, Brian McNamee, also provided human growth hormone to Clemens’ New York Yankees teammate Andy Pettitte, who wanted to speed recovery from an elbow injury.

Former Angels and Boston Red Sox slugger Mo Vaughn, a one-time American League Most Valuable Player, acquired human growth hormone when he was recuperating from a serious ankle injury. The report reproduced copies of checks for $3,200 and $2,200 written to a trainer who provided the hormones.

Former Dodgers relief pitching ace Eric Gagne had human growth hormone shipped directly to the clubhouse at Dodger Stadium. And former Dodgers catcher and fan favorite Paul Lo Duca thanked his drug supplier with a handwritten note on Dodger Stadium stationery.

Adding to the impact of Mitchell’s report was his extensive use of canceled checks and other documents, among them internal correspondence from front offices in Los Angeles and Boston indicating that management knew about drug use and took it into consideration during trade talks.

“Everyone involved in baseball -- the commissioner, club officials, the players’ association and the players -- shares responsibility,” Mitchell said.

Mitchell urged baseball Commissioner Bud Selig to grant amnesty to players in the interest of moving forward, but Selig pointedly reserved the right to suspend any active players cited by Mitchell.

Selig, who appointed Mitchell to conduct the investigation, had hoped the report would satisfy congressional critics pressing for reform. However, within two hours of its release, Selig was summoned for hearings before two committees in the House of Representatives.

Critics sounded off from all sides.

Clemens’ attorney Rusty Hardin issued a statement denying the pitcher used steroids and all but threatening a lawsuit. The Houston attorney said: “There has never been one shred of tangible evidence that he ever used these substances and yet he is being slandered today.”

Hardin also complained that Clemens has “no meaningful way to combat what he strongly contends are totally false allegations. He has not been charged with anything, he will not be charged with anything and yet he is being tried in the court of public opinion with no recourse. That is totally wrong.”

Jose Canseco, who fingered former teammates as steroid users in a book referenced in Mitchell’s report, expressed disappointment in its contents. He called the report “a slap on the hand” and said some names of drug users were missing. He told Fox Business Channel that New York Yankees star Alex Rodriguez should have been included.

“I could not believe that his name was not in the report,” Canseco said. Scott Boras, Rodriguez’s agent, did not respond to messages seeking comment.

Besides Clemens, Pettitte and Vaughn, other stars listed by Mitchell included former Dodger Kevin Brown, David Justice and Barry Bonds. Another former Most Valuable Player on the list, Miguel Tejada, was recently traded from the Baltimore Orioles to the Houston Astros.

“Other investigations will no doubt turn up more names,” Mitchell said.

Selig said he commissioned this investigation against the wishes of his closest advisors. The probe is believed to have cost owners more than $20 million, but neither Mitchell nor Selig would provide a figure.

“If there were problems, I wanted them revealed,” Selig said. “If there were individuals who engaged in wrongdoing, I wanted those facts to come to light. If there were recommendations that would improve our drug testing program, I wanted to improve them. His report is a call to action. And I will act.”

Mitchell issued a series of recommendations, among them to let a third party independent of owners and players run the sport’s drug testing, to increase random year-round tests, to establish an investigative unit to pursue allegations of drug use beyond testing and to record every package received by a player in a clubhouse.

Selig said he would implement all recommendations that do not require union consent and ask the players’ association to discuss the rest “in the immediate future.” Donald Fehr, executive director of the association, said the union would consider Mitchell’s recommendations. Selig also said he would convene an “HGH summit” shortly.

Mitchell’s report indicated human growth hormone has replaced steroids as the performance-enhancing substance of choice because baseball does not test for human growth hormone.

The owners have funded research for a urine test -- and Fehr said the players would agree to such a test if one can be developed -- but said current blood tests for human growth hormone are of “dubious or little practical value.”

In his report, Mitchell cited a “widespread misconception” that baseball did not ban steroids and other performance-enhancing substances until 2002. Baseball expressly prohibited the illegal use of steroids as far back as 1991, according to the report, but did not test for them until 2003.

Although the union had consistently opposed testing without reasonable cause, thus “delaying the adoption of mandatory random drug testing in major league baseball for nearly 20 years,” Mitchell also chided owners for not pushing for testing sooner “because they were much more concerned about the serious economic issues facing major league baseball.”

Said Mitchell: “With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that baseball missed the early warning signs of a growing crisis.”

In general, Mitchell said, his corroboratory evidence included other interviews, phone records, shipping documents, canceled checks and money orders.

“Many players are named, their reputations adversely affected forever,” Fehr said, “even if it turns out down the road they should not have been.”

Fehr said he welcomed Mitchell’s suggestion that active players not be suspended but said the union would fight on behalf of any player who might be disciplined. Mitchell said Selig should grant amnesty to those players and look to the future.

Said Mitchell: “Spending more months, or even years, in contentious disciplinary proceedings will keep everyone mired in the past.”

Yet Selig insisted he would consider suspensions “on a case-by-case basis” and act “swiftly” in doing so. “I think, frankly, that is a byproduct of this investigation that I need to address.”

The Kansas City Royals signed outfielder Jose Guillen for $36 million last week, well aware he would be suspended for reportedly ordering steroids and human growth hormone. On the day Guillen signed, Selig suspended him for 15 days.

Times staff writers Dylan Hernandez and Lance Pugmire contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.