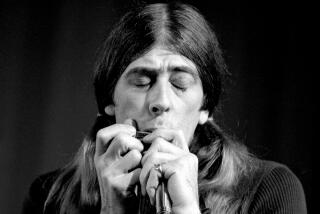

This bluesman knows whereof he sings

Things were just beginning to pick up at the House of Blues on Sunset Boulevard when in the private bar upstairs, the big man took the stage. His voice, deep and gravelly, rumbled through the room.

“If ya’ll love the blues, let me hear you say, yeah!”

Soon, he had the room grooving:

Ah, oh, smokestack lightning, shinin’, just like gold. Why don’t ya hear me cryin’? Ah, whoo hoo!

When Artwork Jamal plays here — in a crisp white shirt and a lavender tie — the crowd is mesmerized. He falls to one knee and serenades the ladies. He hawks his CDs, “free — with a $15 handling fee.” He sticks around after he’s earned his $50 and enjoys prime rib on the house.

Then he’s back to his tiny skid row studio and his mountain of pills — for diabetes, lung disease, congestive heart failure and for the voices that can creep into his head. Back to hustling for a buck to buy a taco.

At the pawn shop on Broadway, they know Jamal by heart: first name, last name, date of birth.

He shows up each month — 350 pounds in a motorized wheelchair — to hand over his speakers, his amplifiers, his computer, his wife’s wedding ring. When things get really bad, he brings in his two guitars.

“That’s the blues,” said Jamal, 45. “I sing the blues. I live the blues.”

He’s been living them and fighting them since he was young.

It’s how he was raised, never to give up.

::

His mother and grandmother weren’t the kind to brook excuses. Artwork Jamal grew up in a Mid-Wilshire household where everything was meant to motivate: the books on the shelves, the posters on the wall, the chatter at the dinner table:

Get up, get busy, get active…. Nothing will take the place of persistence.... Always put your best foot forward.

Elizabeth Harris adopted him as a baby and named him Arthur Harris III. Six years later, she got him a little brother. With help from her mother, the Occidental College education professor raised Arthur and Nyles to shine.

They performed in talent shows and appeared in TV commercials. They were trained to sing and to play the piano and trumpet. One Christmas, Elizabeth got Arthur a keyboard synthesizer. The moment he saw it, parked in front of the tree, he fell in love.

For the first time, he could make up his own music. By 14, he was on his third band and determined to record a demo. His mother helped him make the pitch to Motown. “When the family attorney showed up with all these papers to sign, I thought I was ready to hit the big time,” Jamal said. “I was ready to be Michael Jackson.”

The deal, in the end, went nowhere, but it convinced Jamal that he could be a famous entertainer, or perhaps a top music engineer. After high school he seemed well on his way: He earned a spot at the prestigious Berklee College of Music in Boston.

It was then the voices showed up.

He started hearing them a few months before he was due to leave. Usually it was a man, issuing warnings. People were out to get him — on the street, outside his window. The neighbor. The cashier. The bus driver. When Elizabeth noticed, she rushed him to therapists, who diagnosed his illness as paranoid schizophrenia. They prescribed pills to help him fend off delusions at Berklee.

But the medicine hardly helped. He made it on a train only as far as Chicago before the voices got too strong and his mother had to fetch him. A few months later, he tried again. He was back within the week, on a plane ticket paid for with the semester’s spending money.

“I said, ‘Hey, I’m here,’” Jamal remembers. “I couldn’t focus. I couldn’t think. We knew then I needed to be close to home.”

For nearly five years, starting at age 19, Jamal hardly left the house. He couldn’t even make it to see Nyles graduate as high school valedictorian. He tried. He got into the car. But then he couldn’t get out.

Get up, get busy, get active. His mother bought a thick book, “Surviving Schizophrenia: A Family Manual.”

“That became our bible,” Jamal said.

The only thing that hushed his head was music. He wrote songs and put them on tapes he labeled in neat letters: “Diary of a Schizophrenic,” “Artwork’s Faded Colors.”

He dropped Arthur for Artwork, to express his creative nature. He later added Jamal in tribute to former Lakers star Jamaal Wilkes.

His childhood friend Thurman Green visited during those housebound days. “He was always focused on the music,” Green said. “Like, ‘Hey, listen to these tracks. Listen to these lyrics.’”

In his bedroom, Jamal had all he needed: a multi-track recorder, a mixing board, a computer, keyboards and speakers. He tinkered and practiced and, with help from magazines, taught himself the basics of record engineering.

At 25 he left home, the pills now keeping the voices at bay. He got a job at Paramount Recording Studios in Hollywood, making $8 an hour mixing tapes for artists.

Ten years later, he had his own little studio — Graphic Sounds Arts — with a staff of seven and a list of clients.

“He was the tech man in town, a hell of an engineer,” said William Lucas, a record engineer for 18 years who became friends with Jamal after working with him in the mid-1990s. “Whatever you needed, you knew you could touch base with him.”

But the good times in Jamal’s life never lasted long. In 1995, his mother was diagnosed with bone cancer, then Alzheimer’s. His grandmother was showing signs of dementia. And Nyles was away in the Bay Area, working as a computer engineer after graduating from Stanford.

So Jamal closed his studio and dedicated himself to caring for the two women.

They lived off pensions, disability checks and the sale of his childhood home. They moved around — to North Hollywood, Reseda, Lancaster, Glendale and up to the Bay Area, to live with Nyles. Jamal struggled each day to cook meals, prepare baths and change diapers.

Once of average size, he ballooned to 428 pounds. He had to be hospitalized every so often because of his weight.

In 2006, his grandmother died at 100. Two years later, he lost his mother.

“It was a whole new world,” he said. “I had to stand on my own two feet from that point on. Whatever came, I had to deal with it.”

::

At the swanky Seven Grand bar downtown, people drop in to sip whisky. But this night, with his band behind him, Jamal was ready to give them a show.

He launched into Muddy Waters’ “Mannish Boy”: Now, when I was a young boy, at the age of five, my mother said I was gonna be the greatest man alive…

If Elizabeth were around, she surely would be proud, Jamal said. Any mention of her or his grandmother and the big guy still chokes up. Cheering him on now is Lida Parent Harris, his wife, whom he met through his mother’s caretaker and married three years ago.

Lida dotes on him. She hands him water during shows. And when the voices occasionally whisper in his ear, she pulls him back.

He does the same for her. She’s struggled with schizophrenia for a decade, though she’s not as comfortable talking about it.

Each day, she makes sure she and Jamal take their medication, that they don’t withdraw or make impulsive decisions.

“Whatever challenges we’ve been through, we’ve been through them together,” she said.

With her help, Jamal returned to his performing after his mother died. It seemed the natural thing to do.

“I am a showman,” Jamal said. “I’ve done other things, but I belong onstage.”

He needs the wheelchair to get to gigs but pushes it aside before the show begins.

His look and that powerful voice have opened doors. He started at local bars, then went to Las Vegas and San Francisco. Last year, he performed before 10,000 people at the Monterey Blues Festival. And he was named the Bay Area Blues Society’s male vocalist of the year, beating out blues singers from around the nation.

“You hear him sing, and you think, ‘Damn,’” said Ronnie Stewart, the society’s executive director. “He’s got that voice, the kind you don’t hear anymore. He takes you back to the legends and the pillars.”

The recognition has yet to ease his life. On good months, Jamal makes $600; on bad months, half that. He and Lida get by without a car and live off $1,500 in disability checks and the pawnshop loans.

“There are days when I am literally singing for my supper,” Jamal said, sitting on the floor of his apartment at the Rosslyn Hotel.

Down in the lobby, worn-down souls drift in and out and a man sits behind the counter shielded by bulletproof glass, demanding IDs from visitors. The studio is tiny, without room for a sink or a stove. Jamal sleeps in a sofa chair, Lida on a futon that extends into a bed.

Before a show at a downtown bar, he rested beside her and reached for a cigarette.

“I’ve seen hard times,” he said, taking a drag. “But there but for the grace of God, go I.”

He paused, then grinned.

“I have big plans. I don’t plan to stay in this little room and sing the blues. I’ve got things to do.”

Not far from his bare feet sat a sort of shrine: his grandmother’s ashes in a metal box. His mother’s survivor’s manual, marked with her initials. His guitar and his beat-up tip can.

esmeralda.bermudez@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.