Man’s murder conviction is reduced to voluntary manslaughter

After fatally shooting his unwanted houseguest in the head, Robert Charles Redd stuffed the man’s body into a recycling bin and wheeled it into a room of his Pico Rivera home.

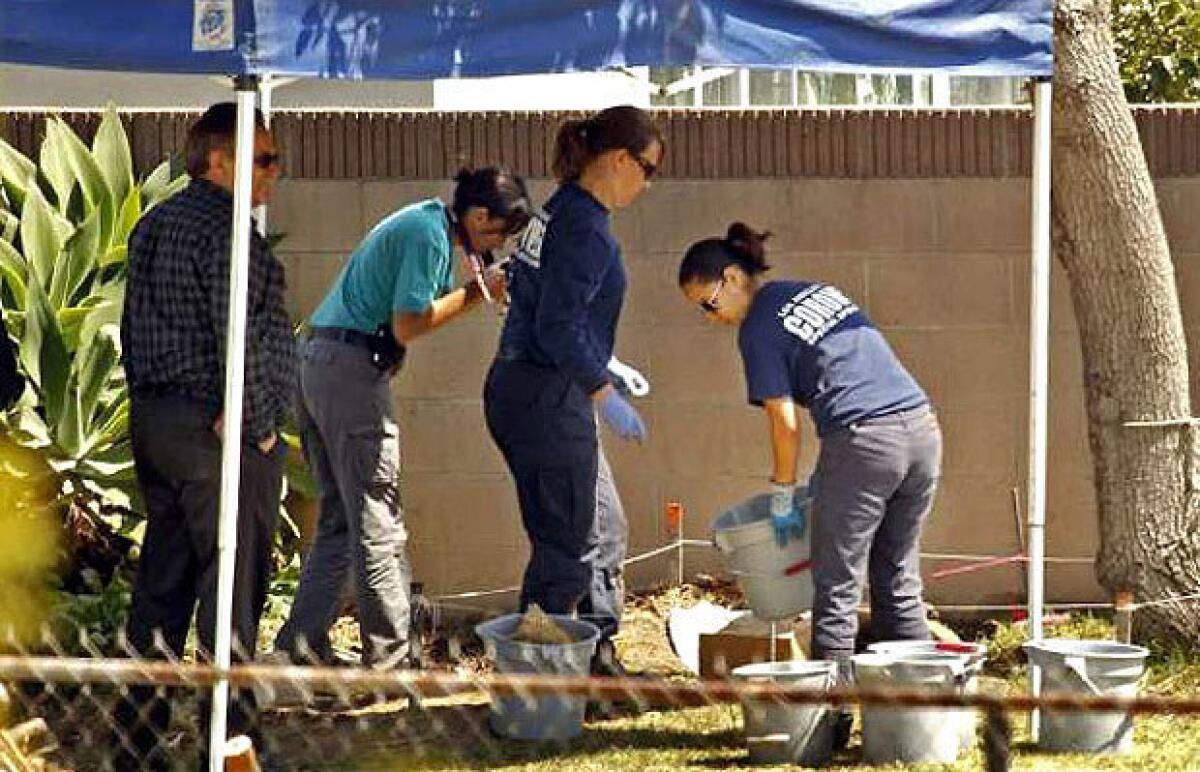

When the stench of death grew too overpowering a couple of days later, Redd wheeled the bin out into the backyard and tipped Joseph Rubalcaba’s corpse into a shallow grave that he topped with plants.

Last month, a Norwalk jury convicted Redd, 53, of second-degree murder.

But in an unusual move, a judge recently reduced Redd’s conviction to voluntary manslaughter, finding that Redd feared for his life when he fired the fatal shot. Instead of receiving a mandatory sentence of 40 years to life in prison for murder with a gun, Redd was sentenced to 10 years.

The ruling, which prosecutors are considering appealing, drew fierce criticism from the 19-year-old victim’s family, who said they were shocked when it was announced.

“The shock is wearing off and the pain is coming in,” Rubalcaba’s aunt, Melinda Rodriguez, said later. “He’s being treated like a piece of trash by the judge. I don’t understand the judicial system.”

Superior Court Judge Raul A. Sahagun’s decision to change a jury’s unanimous verdict highlights judges’ seldom-used power to act as a sort of 13th juror in criminal trials, giving them the ability to modify a jury’s verdict if they conclude the evidence proves a defendant was actually guilty of a lesser crime.

Relatively rare, such calls have generated controversy.

In 2002, a San Francisco judge drew condemnation for reducing a second-degree murder conviction to involuntary manslaughter for a woman in a high-profile dog-mauling case. The jury’s verdict was later reinstated after an appeal.

In 1997, a Massachusetts judge made international headlines when he reduced the verdict in the baby-shaking trial of a British au pair, finding that the teenager did not act with the malice necessary for murder.

And a year earlier, over the objection of prosecutors, a Los Angeles judge modified a second-degree murder conviction to voluntary manslaughter in the case of a North Hollywood apartment house manager who fatally shot a fleeing car burglar.

Laurie Levenson, a professor at Loyola Law School, said judges generally defer to a jury’s decision but that they also have the duty to independently weigh the evidence and make sure that jurors reached a fair verdict.

“We consider judges as safety nets,” she said.

In the Redd case, the jury and judge wrestled with whether Redd feared for his life when he shot Rubalcaba. Redd would be guilty of voluntary manslaughter if he believed — unreasonably — he was in imminent danger and that he needed to use deadly force.

Redd’s defense relied on the account he gave sheriff’s investigators shortly after the killing, according to court records.

Redd, who was living in a house his father owned on Pico Vista Road, said he was introduced to Rubalcaba by mutual friends sometime in May 2011 and offered to let him stay at the house in exchange for methamphetamines.

According to Redd’s statement to investigators, Rubalcaba, a member of the Rivera 13 street gang, soon brought other members of the gang to the home and failed to supply Redd with the promised drug. In early July 2011, Redd told him he could no longer stay at the house.

Redd said Rubalcaba became furious, tied him up, pointed a gun at him and repeatedly threatened to kill him. Rubalcaba told him that the home now belonged to him and his gang. Redd said he was in fear for his life from then on.

Redd said that on the morning of July 18, 2011, he saw Rubalcaba cleaning a handgun at the kitchen table and thought his housemate intended to kill him. Redd retrieved a pistol from his bedroom and confronted Rubalcaba, demanding that he put the gun down.

“What are you going to do about it?” Redd said Rubalcaba responded.

Rubalcaba’s family discovered his buried body after becoming concerned by his disappearance and conducting a search.

Redd’s attorney, Deputy Public Defender Christine Rodriguez, described Rubalcaba in court papers as a “violent gang member who was always armed with a gun.” At the trial, witnesses detailed his history of violence, including a robbery at gunpoint five days before his death, the lawyer wrote. He had numerous gang tattoos, including “Rivera” over one eyebrow and “kills” over the other.

Deputy Dist. Atty. Brandon K. Wong said he argued during the trial that Redd had concocted the story about Rubalcaba having a gun and that the shooting was over Rubalcaba’s failure to supply Redd with drugs.

He noted that Redd told sheriff’s detectives he threw the victim’s pistol into the San Gabriel riverbed behind his home, but authorities were unable to find the weapon despite using weapons-sniffing dogs and volunteers with metal detectors.

In a report to the court, a probation officer wrote that the fear Redd claimed to feel, “if true, can never mitigate the vicious and callous actions by the defendant further shown by burying the victim in his own backyard.”

At a hearing on May 9, Wong argued that Redd had lied about the shooting when he told detectives that the victim was standing face-to-face with him when he opened fire. The prosecutor noted that coroner’s officials found that Rubalcaba was shot once in the top of his head.

But Sahagun said much of Redd’s statement to sheriff’s investigators “had a ring of truth to it,” according to a transcript of the hearing.

There was no doubt that Rubalcaba was a violent gang member, the judge said, adding that there was strong evidence that the victim did have a gun that day. He said that Redd’s decision to bury the body could have been the result of “his very real fear of retaliation” from the victim’s gang.

Sahagun concluded that Redd believed that his life “was in imminent peril” but that his belief was unreasonable.

Rubalcaba’s relatives complained to the judge that the victim had been unfairly characterized as a violent gang member. He was far more, they said, describing him as a caring, inquisitive “mama’s boy” who did well at school but made bad choices and associated with the wrong crowd. His killing, they said, devastated his family.

“He was always the love of my life,” his mother, Lupe Rodriguez, told Redd at the hearing. “It’s like if you pulled the trigger on our head and buried us with him.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.