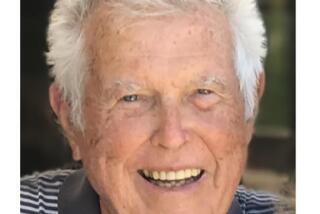

Betty Skelton dies at 85; record-setting aviatrix and auto racer

Betty Skelton, an audacious aviatrix and stock-car racer often called the “First Lady of Firsts” for her record-setting feats in airplanes and automobiles during the 1940s and ‘50s, died Aug. 31 in The Villages, Fla. She was 85 and had cancer.

Her death was confirmed by Dorothy S. Cochrane, a longtime friend and curator of general aviation at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

Skelton held “more combined aircraft and automotive records than anyone in history,” according to a biography on the museum’s website. A three-time women’s international aerobatics champion, she was the first woman to execute the “inverted ribbon cut,” a breathtaking maneuver in which a pilot flies upside down about 12 feet from the ground to slice a ribbon strung between two poles. She also set two world light plane altitude records, reaching 26,000 feet in 1949 and 29,000 feet in 1951.

FOR THE RECORD:

Betty Skelton: In the Sept. 11 California section, the obituary of aerobatics pioneer Betty Skelton, who later achieved firsts in the auto industry and in auto racing, said she was an inductee of the NASCAR International Motorsports Hall of Fame. The correct name of the organization is the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America. —

She donated her diminutive biplane — a red-and-white Pitts Special she dubbed “Little Stinker” — to the Smithsonian, which placed the aircraft on permanent display above the entry to its Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Va.

After retiring from stunt flying, Skelton became the first female test driver in the auto industry and the first woman to drive an Indy car. She set a land speed record in 1956, hitting 145 mph in a beefed-up Corvette.

She was the first woman inducted into the International Aerobatic Hall of Fame and the NASCAR International Motorsports Hall of Fame.

“She enjoyed speed, mechanical technology, from cars to boats to planes,” Cochrane said. “She was an unusual young girl and young woman to be interested in that. She was not interested in an ordinary, quiet life.”

Born June 28, 1926, the year before Charles Lindbergh made his historic transatlantic flight, Skelton grew up watching Navy pilots perform stunts in the skies above her Pensacola, Fla., home. While other girls were playing with dolls, she collected model airplanes and talked her parents into paying for flying lessons when she was 10.

At 12 she made her first unofficial solo flight. “I didn’t tell my mother for about a week,” she recalled in a NASA oral history interview in 1999.

She soloed officially at 16, when she earned her pilot’s license.

Too young to join the quasi-military Women Airforce Service Pilots during World War II and barred from commercial aviation because of her gender, Skelton turned to aerobatics, performing in her first show in Florida in 1946.

She bought Little Stinker — a nickname inspired by the plane’s tendency to make a ground loop on landing — in 1948, the same year she won her first international aerobatics championship. The single-seat, open-cockpit plane was only 4 inches taller than the 5-foot-2 Skelton, whose agility and precision as a pilot helped make the plane the top choice of aerobatic fliers.

Skelton embarked on her second career after meeting NASCAR founder Bill France, who persuaded her to drive the pace car at Daytona Beach during Speed Week. She went on to set four women’s world land speed records and a transcontinental speed record in 1956, driving from New York to Los Angeles in just under 57 hours.

In 1959 Look magazine arranged for her to train with the Mercury 7 astronauts and featured her on the cover for a 1960 article titled “Should a Girl Be First in Space?” She underwent the same physical and psychological tests as the seven male astronauts, who nicknamed her “No. 7 1/2.”

“The astronauts were all terrific to me,” she recalled in a 2004 interview for the Fort Pierce (Fla.) Tribune, “but I knew it was primarily because they knew a woman was not going to be in the program. And there wasn’t, for 20 or 25 years.”

Skelton also worked in advertising and in real estate. She married TV director and advertising executive Donald A. Frankman in 1965. He died in 2001.

Her only survivor is her second husband, retired Navy doctor Allan Erde, whom she married in 2005.

Almost nothing scared the gutsy aerobatics pioneer. She navigated planes in violent storms and dense fog. One time the engine of a P-51 Mustang exploded in midair when she reached a record-breaking speed of 421 mph. A non-swimmer, she declined to bail out over Tampa Bay and steered to a safe landing.

“I think I’m more afraid of snakes than I am of airplanes,” she told the Fort Pierce paper. “I’m just horrified of snakes.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.