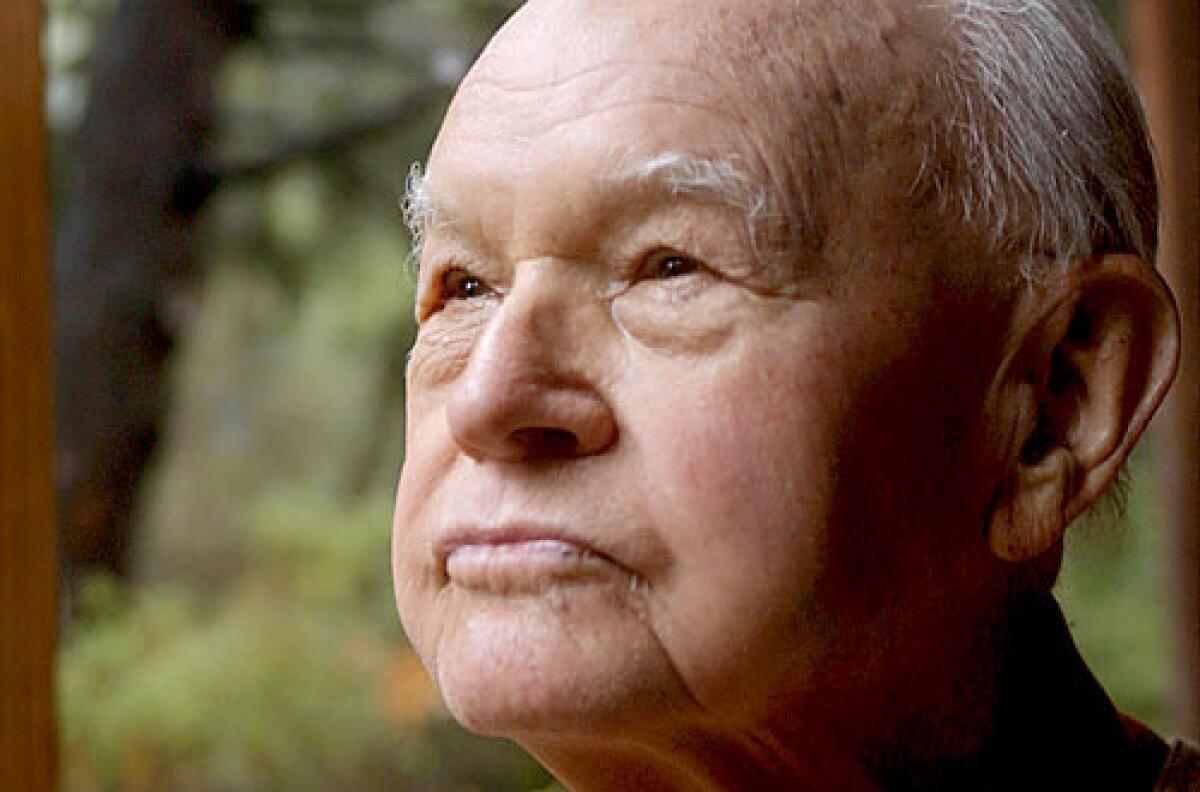

Pirkle Jones, California photographer, dies at 95

Pirkle Jones, a California photographer admired for his stirring images of migrant workers, endangered landscapes and social movements, including a controversial series on the Black Panthers at the height of their activism in the late 1960s, died March 15 in San Rafael. He was 95.

The cause was heart failure, said his assistant, Jennifer McFarland.

Jones’ artistic sensibility was formed during a golden era in the history of photography in the West, when he joined the first class taught by Ansel Adams at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute) in 1946.

His work over the next seven decades blended “the two strands of what California photography at a certain time was -- the strand typified by Ansel Adams and the strand typified by Dorothea Lange. . . . But his work was more overtly political,” said Tim Wride, who curated a major Jones retrospective at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in 2001 and wrote an essay for a book published the same year, “Pirkle Jones: California Photographs.”

Jones’ photographs had technical mastery and visual crispness reminiscent of Adams but also a strong sense of social purpose that made him a kindred spirit to Lange, the legendary Depression-era documentary photographer.

His best-known work includes a collaboration with Lange called “The Death of a Valley 1956,” which portrayed the Berryessa Valley in Napa County during the year before completion of the Monticello Dam that flooded the valley; “Walnut Grove 1961,” a series Jones shot with his wife, Ruth-Marion Baruch, which documents a dying Sacramento River town; and “Black Panthers 1968,” also in collaboration with Baruch, which caused a furor for its sympathetic view of the black power movement.

“I think that Pirkle Jones is an artist in the best sense of the term,” Adams once wrote of his student. “His statement is sound and resonant of the external world as well as of the internal responses and evaluations of his personality. His photography is not flamboyant, does not depend upon the superficial excitements. His pictures will live with you, and with the world, as long as there are people to observe and appreciate.”

Jones was born in Shreveport, La., on Jan. 2, 1914. One of seven children in his family, he said his parents “ran out of names” and named him after “Dr. Pirkle,” the physician who delivered him.

When he was 3, his family moved to an 80-acre farm in southern Indiana, which opened his eyes to nature. His family moved a few more times, and he graduated from high school in Lima, Ohio.

He was stunned by the beauty of photos by Alfred Stieglitz during a visit to a Cleveland gallery in the mid-1930s; the inspiration he found there stayed with him for a decade before he could act on it.

From 1933 to 1941, he worked in a shoe factory in Lima. Then he was drafted into the Army in 1941 and served in the South Pacific during World War II. When he was discharged in 1945, he decided to study photography on the GI Bill.

At the California School of Fine Art, he found himself in a creative community that included not only Adams but Lange, Edward Weston, Minor White and Imogen Cunningham. He became Adams’ assistant in 1949 and taught at the school for 28 years, beginning in 1952.

He also met Baruch at the school, and they were married in 1949 at Adams’ home in Yosemite. Baruch died in 1997. She and Jones had no children.

According to Wride, Jones and his mentor disagreed about the extent to which political concerns entered into Jones’ art, but Jones saw the simple act of taking a photograph as a political act. “There’s no such thing as objectivity,” he once explained in an interview.

Jones, who with his wife belonged to the Peace and Freedom Party, made no secret of the fact that his purpose in photographing the Black Panthers was, as he told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2002, “to show them the way we saw them -- as human beings.”

During the four months in 1968 that he and Baruch focused their lenses on the radical group, they produced a number of emblematic shots from the campaign to free Huey P. Newton, the Panther leader who was facing voluntary manslaughter charges for the murder of an Oakland police officer.

Jones captured the somber expressions in a crowd of people gathered under a tree at a rally, the front window of Panther headquarters in Oakland shattered by bullets that had been fired by Oakland police and a trio of Panther guards standing erect in black leather jackets and berets, waving “Free Huey” flags on the steps of the Alameda County courthouse.

Kathleen Cleaver, Eldridge Cleaver’s wife and the party’s communications secretary, instantly recognized the power of the last image and said “That’s a poster!” Jones took the photo to a printer himself and brought back 1,000 posters.

The Panther photographic essay caused an uproar; even Adams advised Jones to drop the project. The controversy almost caused San Francisco’s De Young Museum, which was mounting them in a show, to cancel the exhibition, but after union leaders and art critics intervened, the museum went ahead with its plans. The show drew 100,000 visitors.

“At that time, people were upset that we were doing this,” Jones told The Times in 2004, when a new show featuring the photos opened at the 18th Street Arts Center in Santa Monica.

“I had professional clients who said, ‘What in the world are you doing photographing Panthers?’ I’d just sort of shrug my shoulders. I did not make a big speech about it. I did the talking through the photographs.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.