Editorial: The indictment of Julian Assange is an attack on the freedom of the press

The freedom of the press to publish information of public importance — even if it has been classified as secret by the government — is a vital check on official wrongdoing and deception. However grudgingly, presidential administrations of both parties have accepted that reality by declining to prosecute media organizations under the Espionage Act.

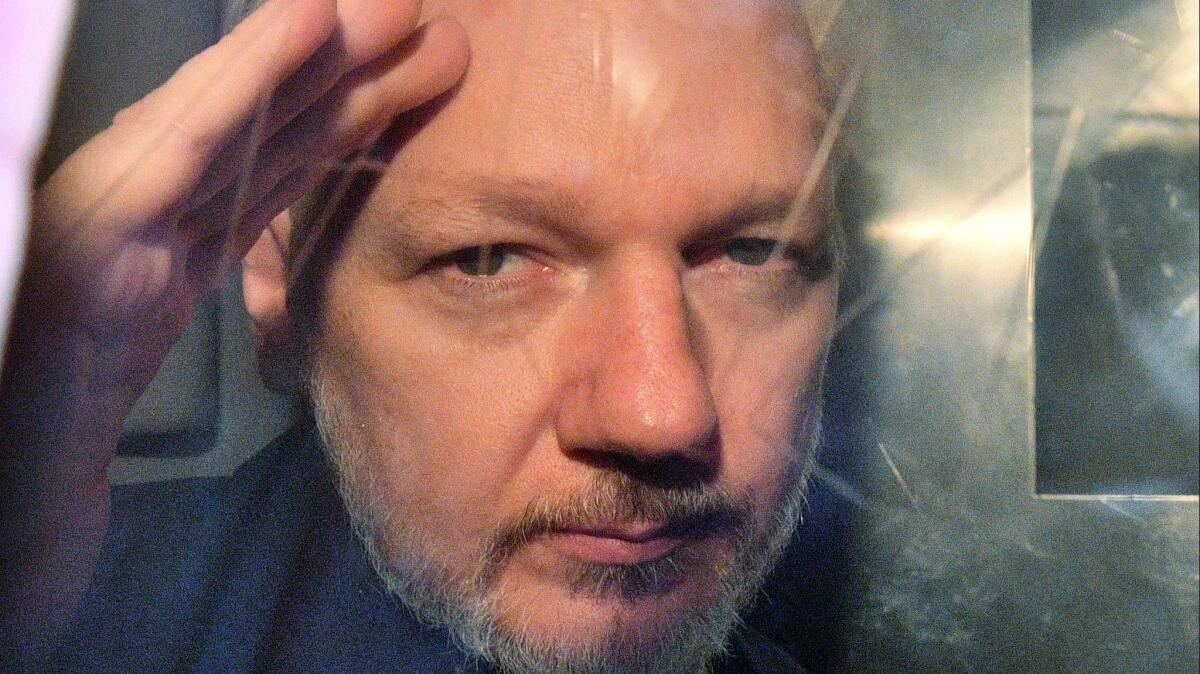

Now the Trump administration has departed dangerously from that policy, bringing new charges Thursday against Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks, in connection with the thousands of secret documents he obtained from former Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning and then published on his site.

Assange is an unsympathetic figure, to put it mildly, and WikiLeaks is not a traditional journalism organization. (In addition to publishing the military and diplomatic documents obtained from Manning, WikiLeaks is best known for having posted emails from the Democratic Party that U.S. officials said were hacked by Russia.)

But in prosecuting Assange for soliciting classified information from Manning and then disseminating it, the Justice Department has adopted a legal theory that could potentially make criminals of many conscientious reporters who cover defense and national security. After all, journalists routinely urge their sources to divulge official secrets, and they routinely publish them, as part of their mandate to report truthfully about what happens behind the closed doors of government. Criminalizing that behavior would be an affront to the 1st Amendment, which singles out the press for special protection from intrusion and censorship.

The decision to prosecute those accused of publishing classified information would be troubling regardless of who occupied the White House.

The charges announced Thursday replaced an earlier — and more restrained — indictment that was unsealed in April. The previous indictment accused Assange not of Espionage Act violations but of conspiracy to violate a law against “computer intrusion.” It alleged that Assange conspired with Manning to crack a government password in search of secret material.

At the time, this page expressed some relief that the indictment focused mostly on the allegation that Assange conspired to facilitate the theft of information rather than that he received it or published it.

The new, more sweeping indictment goes much farther. It says that Assange “repeatedly encouraged sources with access to classified information to steal and provide it to WikiLeaks to disclose.” The indictment also accuses Assange of violating the law by “publishing [documents] on the internet.”

The indictment acknowledges that part of WikiLeaks’ mission is to “disclose ... information to the public.” That was also the reason the New York Times published the Pentagon Papers, a classified history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, almost half a century ago. It’s also the reason many newspapers reported on some of the information provided to WikiLeaks by Manning, including a video of an Apache helicopter attack that killed 12 civilians in Baghdad in 2007.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute »

In announcing the new indictment, Assistant U.S. Atty Gen. John C. Demers insisted that the department “takes seriously the role of journalists in our democracy” and doesn’t target journalists for their reporting. He maintained, however, that “Julian Assange is no journalist.” That was clear, Demers said, from the allegation in the indictment that Assange published, without redaction, the names of individuals in war zones who had provided information to the U.S.

It’s true that a responsible news organization generally wouldn’t publish the names of informants who might face danger. For example, the New York Times in publishing material from WikiLeaks withheld the names of informants and operatives. But the issue isn’t whether Assange is a journalist (or a responsible one); it’s whether the government is setting a precedent in which it criminalizes those who publish classified information rather than merely those who leak it. If it uses this new legal theory against Assange today, it can use it against Seymour Hersh or the Los Angeles Times or any other legitimate news organization tomorrow.

As Bruce Brown, executive director of Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, put it: “Any government use of the Espionage Act to criminalize the receipt and publication of classified information poses a dire threat to journalists seeking to publish such information in the public interest, irrespective of the Justice Department’s assertion that Assange is not a journalist.”

The decision to prosecute those accused of publishing classified information would be troubling regardless of who occupied the White House. But the current president has relentlessly railed against “fake news,” called journalists “enemies of the people” and suggested he might have to “get involved” in the operation of the Justice Department. That makes this unnecessary change of course especially unsettling.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.