Misinformation about the coronavirus abounds, but correcting it can backfire

The plot had all the elements of a big-budget thriller: Put an untested gene therapy technology in the hands of unscrupulous scientists. Make them soldiers of a greedy pharmaceutical company. Then give them the protection of a secretive and authoritarian government that will stop at nothing to achieve world domination.

They will, of course, unleash a deadly new virus on the world.

On Twitter last week, more than 2.5 million followers of the financial blog ZeroHedge saw this plot spun as the origin story of the new coronavirus from China that is spreading across the globe.

The rumor circulated briefly on several social media platforms before Twitter shut down the ZeroHedge account for violating its rules against “deceptive activity that misleads others.” But by then, it had been posted, shared or commented upon more than 9,000 times, according to the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Stamping out falsehoods about the coronavirus will require much more than blocking a Twitter account. Indeed, thanks to the way we are wired to process information about new and mysterious threats, it may be all but impossible, experts say.

“Misinformation is a worrisome consequence of any emerging epidemic,” said Dartmouth College political scientist Brendan Nyhan, who studies conspiracy theories and those who believe them. “But the assumption that facts and science alone are going to be decisive in countering misinformation is wrong, because they often aren’t.”

If the coronavirus outbreak in China were a Hollywood movie, now would be time to panic. But in real life, most Americans have no need, experts say.

Researchers from a variety of disciplines have examined why people believe things that have been discredited or debunked. Their efforts have led them to a worrying surmise: Most of us are primed to give some credence to fibs we see or hear. And once we have done so, we’re loath to update our beliefs, even when offered alternatives that are true.

Indeed, efforts aimed at debunking false information can wind up reinforcing them instead.

That presents a serious challenge to the public health officials working to persuade panicked members of the public to remain calm.

Some of the untruths about the coronavirus appear motivated by commercial interest. Others seem driven by ethnic suspicion and xenophobia. Still others have speculated that the coronavirus is a bioweapon developed by China to kill Uighur Muslims, or by the United States to destroy the Chinese economy.

The problem with conspiracy theories is that they often seem to have some whiff of truth. That makes them just plausible enough to be credible.

Some rumors connect the virus to unfounded yet well-established beliefs, such as those linking vaccines to autism and genetically modified foods to health risks. In social media communities devoted to those beliefs, speculations about the coronavirus circulate daily, said Joshua Introne, a computer scientist at Syracuse University who studies the evolution of conspiracy theories online.

“We like things that support what we believe,” Introne said. Embracing those stories tends both to deepen our convictions and to prompt us to share them with others of like mind, he added.

In many ways, misinformation has a built-in advantage over the truth.

A person doesn’t have to believe every aspect of a conspiracy theory to keep it going. If just one component of the story jibes with her beliefs — a suspicion of China, say, or a conviction that drug companies would do anything for money — that could be enough to make her want to share the story, and perhaps suggest some further plot twist.

The more tropes that can be woven into a conspiracy theory, the more chances it has to gain a following. The resulting “multiverse” of believers makes it hard to destroy, Introne said.

“There’s just too much there,” he said.

After an electoral season that blurred the line between fact and fantasy, a team of UCLA researchers is offering new evidence to support a controversial proposition: that when it comes to telling the difference between truth and fiction, not all potential voters see it the same way.

Health officials have a natural instinct to counter this misinformation with facts. But research shows how that can backfire.

Correcting misinformation may work briefly, but the passage of time can taint our memories. Sometimes, all we take away from the correction is that there’s bogus information out there, so we’re skeptical when presented with facts that are true.

Sometimes the effort to correct misinformation involves repeating the lie. That repetition seems to establish it in our memories more firmly than the truth, causing us to recall it better and believe it more. Psychologists call this the “illusory truth effect.”

Consider the attempt by health authorities in Brazil to set the record straight about the Zika virus, which took the country by storm in 2015. Most infections resulted in nothing more than mild illnesses, but pregnant women who contracted the virus found themselves at greater risk of suffering miscarriages or giving birth to babies with microcephaly and other birth defects.

The virus is spread by mosquitoes, and the public was urged to wear insect repellent and take other protective measures. Officials made their case by sharing scientifically accurate information about the virus. Yet their efforts caused people to doubt facts that had firm scientific grounding, and false beliefs were still flourishing two years after the outbreak began.

Close to two-thirds of Brazilians believed an unfounded claim that Zika was being spread by genetically modified mosquitoes, according to a study published last month in the journal Science Advances. More than half incorrectly attributed the increased prevalence of microcephaly in newborns to mosquito-killing larvicides. And more than half believed the DTaP vaccine contributed to the uptick in babies born with microcephaly.

Once a participant was prompted to doubt the veracity of some of his Zika-related beliefs, he became more skeptical of any incoming information about the virus, the researchers realized.

When you warn people that there is fake news out there, “they may apply it in an indiscriminate way,” said Nyhan, who worked on the study. “People may doubt all sorts of legitimate information.”

This effect was widespread, and it was evident among respondents whether or not they were inclined toward believing conspiracy theories.

Researchers also know there’s nothing like the allure of something new. The truth doesn’t change, but new falsehoods spring up every day.

After Twitter banned ZeroHedge, traffic on the site appears to have spiked, said Emerson Brooking, a resident fellow at the Digital Forensic Research Lab. That, he said, is a common short-term reaction to a sensational act of conspiracy-mongering.

The proliferation of false and misleading stories about the coronavirus “has contributed to a diminished trust among people in anything they read about the crisis,” including true and well-sourced information, Brooking said.

Nyhan is working on communication strategies to deal with this problem. In experiments, he and a colleague found that instead of just correcting false information, it’s much more effective to replace it.

“A causal explanation for an unexplained event is significantly more effective than a denial,” they reported in the Journal of Experimental Political Science.

It may not be as compelling a tale, but if it’s simple and straightforward, it can fill a gap left by the misinformation, Nyhan said. It’s likely to work best if it comes from a trusted intermediary, such as a barber, pastor or doctor. And when they present the claim being corrected, they should give fair warning that it is false or misleading.

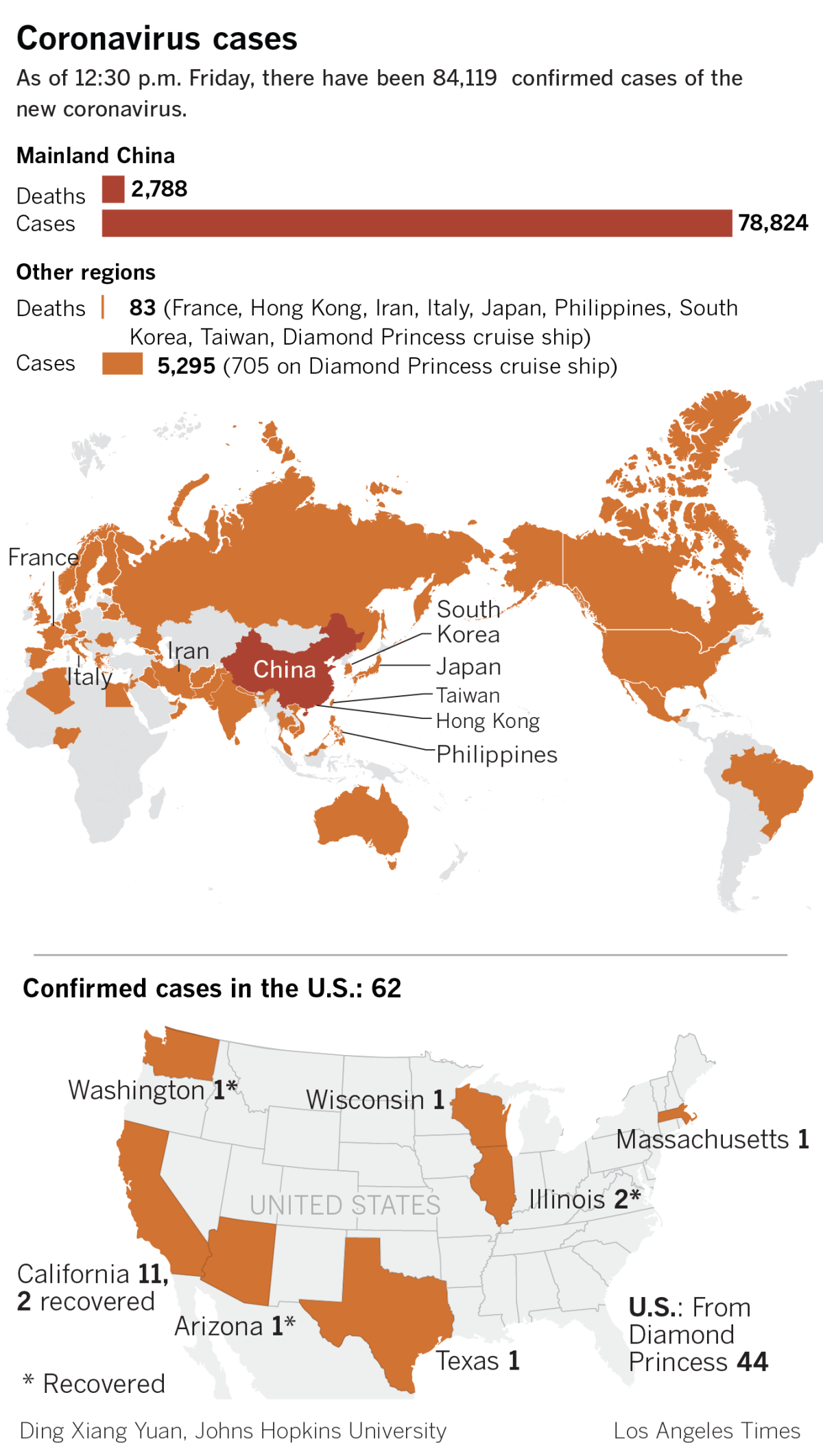

With the coronavirus still taking its greatest toll in Asia, Americans’ willingness to believe untruths about the virus has not reached crisis proportions. But if viral transmission within the United States begins, experts said, the tide of misinformation will rise. And our confidence in what we know to be true — and in what we’re told is accurate — will be put to the test.

“We have lost our gatekeepers, and we have nothing to replace them,” Introne said. “We’ve got to figure this out.”