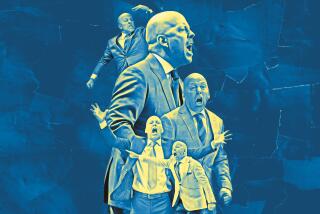

Smiling or scowling, UCLA Coach Ben Howland is a man of many faces

The UCLA basketball team is on a roll, showing hints of becoming special, so these days you get happy Ben Howland, the one who smiles and talks easily, even clapping his hands occasionally.

“It’s good to be winning,” he says.

The Bruins coach is a man of many faces. When his weekly meeting with reporters ends, time to get back to business, he could instantly become the grinder, the one who feels every second slipping past, every moment an opportunity to practice or watch film or jump on a plane to recruit.

That man doesn’t smile as much; he might walk right past with only a nod. And if the Bruins start losing, he might turn surly, flashing his famous temper as he lashes out at players and subordinates.

Howland means different things to different people, a polarizing figure for much of his decade-long tenure at UCLA. Even as the Bruins reached three straight Final Fours, fans wondered if he was the right fit, and the scrutiny has intensified with his team slipping into mediocrity the last few years.

Last season marked a low point. The Bruins foundered as forward Reeves Nelson was dismissed for disciplinary reasons and unnamed sources in a Sports Illustrated article described a program beset by partying and fistfights in practice, suggesting the coach had lost control.

Now, when you ask Howland about the pressure to win — to save his job — you get a narrow grin.

“I mean, you could stress about it all the time, but I’m not going to let that happen,” he says. “I’ve been doing this long enough now.”

Howland is not easy to figure out.

——

It is no secret that players have clashed with the coach over the years. They have grumbled about the constraints of his offensive schemes. They have gone so far as call him verbally abusive.

But it seems that critics speak out only if allowed to do so anonymously. When asked to put their name to a quote, players and former assistants tend to offer praise.

That includes Kevin Love, who bristled at times during his one-and-done season in Westwood but now credits the experience with preparing him for the NBA.

“At the end of the day, I learned things from Coach Howland that I’ll remember for the rest of my life,” Love has said.

Friends describe the 55-year-old Howland as a man who leads almost a double life, intensely focused on basketball around his team and equally devoted to family — wife Kim, grown children Meredith and Adam — at home. They portray him as an introvert.

“When basketball is done, we go fly-fishing and he doesn’t want to talk about it,” said Dave Johnson, who played beside Howland at Weber State. “He does like his privacy.”

This predilection runs counter to a very public job.

When Howland talks to the media or glad-hands at alumni events, “he probably expends a lot of energy, because I don’t think it comes naturally,” said Ross Land, who played for him at Northern Arizona in the late 1990s and remains in frequent contact.

“He has to work at it,” Land said. “He knows he has to do it because he’s at UCLA.”

Ask players about his demeanor around the team and they give a two-part answer. Howland often asks about family and wants to help with difficulties that might arise off-court, they say.

This quality might have worked against him in recent seasons. Many believe Howland went too easy on a pair of troubled athletes — Nelson and Drew Gordon — who became distractions.

“On the outside he might seem like he’s tough, but once you get to know him he’s real kind-hearted and caring,” said Tyler Honeycutt, a former Bruin who now plays for the NBA’s Sacramento Kings. “If you have a problem, he’ll call you into a meeting to talk about it.”

That doesn’t mean he’s the type to buddy up and shoot the breeze. Current center Tony Parker said: “He wants the respect level of an elder, not a peer.”

Parker and others say they are more likely to joke around with younger staff members such as Korey McCray or Tyus Edney.

Tyler Lamb, who recently left UCLA, explained: “That’s why you have assistant coaches who relate well to the players. I feel like this system is designed to work that way.”

——

Anyone who has been around the Bruins for any length of time is familiar with the scenario: The coach walks into an arena or a conference room and immediately complains about feeling too hot or too cold.

A frown crosses Howland’s face as he says, “This stuff about the room temperature — I’ve never once told anybody the temperature had to be this or that.”

Players smile and shake their heads, recalling how often Howland reminds them to put on their sweatshirts before they step outside Pauley Pavilion after practice.

“I’d just say he knows what he wants,” Lamb said. “When he wants something done, he wants it done right.”

This attention to detail has its positive side — opposing coaches praise the Bruins’ ability to prepare for games and run set plays in the half-court offense. It also touches upon the pricklier aspects of Howland’s demeanor.

In August, UCLA was finishing a weeklong visit to China, winning its final exhibition game against a professional team called the Shanghai Sharks, when an arena worker moved Howland’s water bottle from its prescribed spot at the end of the scorer’s table.

The coach scowled and barked, sending a team manager scrambling to remedy the situation. A few minutes later, an assistant lost track of a player’s personal fouls and Howland blew up.

“How many is it?” he hollered. “How many?”

From 2007 through 2010, Joe Hillock spent long days trying to keep the team running smoothly as director of basketball operations. He did not find anything unusual about his former boss.

“Don’t you think most of the good coaches in college basketball are demanding of the people who work for them?” said Hillock, who now coaches high school ball in Utah. “That’s how they got where they are.”

Donny Daniels, an assistant who left for Gonzaga three years ago, described Howland this way: “He’s probably tough on assistants and he’s probably tough on administrators, but whenever Ben got mad at me during games there was always a reason.

“As an assistant coach on any team,” he said, “your job is to figure out why the head coach is upset and solve the problem.”

Another former assistant suspects that Howland’s work ethic makes him impatient.

“Grinders tend to be gruff,” said Scott Duncan, now at Wyoming. “Also, he works 16 or 17 hours a day during the season, so he’s not getting a lot of sleep.”

Critics continue to assert — anonymously — that Howland is abusive. They wonder if his behavior has contributed to a string of players — including Gordon, Chace Stanback and Mike Moser — transferring away.

This season alone, the Bruins have lost Lamb and center Joshua Smith. But, in fairness, Lamb wanted more playing time and Smith was a continual source of disappointment, playing overweight and out of shape.

Howland’s supporters point out that, despite all the turmoil from last season, he wooed four of the nation’s top recruits — Parker, Shabazz Muhammad, Kyle Anderson and Jordan Adams — to Westwood this fall.

“I would say he’s very straightforward and I like that,” Adams said. “He doesn’t sugarcoat anything.”

The coach’s outbursts have become less common in recent months, people around the program say. They talk of a kinder, gentler man.

From a cynical point of view, it would be easy to suggest that he has been forced to change by outside forces, namely negative publicity and job insecurity.

Regardless, one athletic department employee said, “I think he’s really trying.”

——

It was the spring of 2003 when Howland arrived in Westwood to a somewhat mixed review.

Fans welcomed his sense of discipline. They liked the look of his scrappy, overachieving teams at Pittsburgh.

But there were also whispers that then-Adidas rep Sonny Vaccaro had lobbied UCLA administrators to make the hire. And there were questions about Howland’s preference for defense in a place where the basketball sensibilities lean more toward “Showtime” and “Lob City.”

When Howland’s teams fell short in the 2006, ’07 and ’08 Final Fours, losing to opponents who were more athletic and aggressive on offense, the grumbles became louder. Critics doubted that, in this era of high scoring and one-and-done superstars, he could lift the Bruins back to the top.

Growing up in Goleta, Howland used to sprint across the freeway to reach the local gym, then challenge the older kids to games. “A bulldog,” said Hillock, a lifelong friend. Later, at Weber State, Johnson recalls that Howland was “a fireball, an intense kind of guy.”

A predilection for hedging, trailing the shooter and boxing out formed his coaching persona. Even at Northern Arizona, where the Lumberjacks ranked among the best three-point shooting teams in the nation, Land recalls the coach stressing defense.

“And I think he’s always stayed the same,” the former guard said. “Same philosophy.”

UCLA followers have nothing against shutting down opponents. But with a .689 winning percentage through nine-plus seasons, Howland ranks below other post-John Wooden coaches such as Gene Bartow, Gary Cunningham and Jim Harrick.

Some fans still swear by the coach, who has now lasted longer than any of Wooden’s successors. Others have tired of what they perceive as a constrictive half-court offense, an image reinforced by Howland prowling the sideline, seeming to direct every moment.

Players on this season’s team were caught off-guard when, during summer practices, he emphasized pushing the ball upcourt and did not seem terribly concerned about turnovers.

“I was waiting for Coach to stop us and tell us what we did wrong,” forward Travis Wear said. “He just kept us going.”

Howland is still pacing, still yelling, but the message has changed. When the Bruins grab a defensive rebound, he waves at his guards and hollers: “Push, push.”

There are good reasons to play up-tempo, starting with the blue-chip freshmen. Howland also realizes that, with a refurbished Pauley Pavilion and a new Pac-12 broadcast deal, his team needs to shine in the spotlight.

“I think it will be a real positive recruiting-wise,” he said of playing a faster brand of basketball. “I’m not sure it translates to the NBA, but [young players] all want to play that way.”

When UCLA struggled early, eking past UC Irvine and losing to Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, players feared their coach might think twice.

“Luckily, our defense has improved,” Wear said. “I think we’re going to be off to the races now.”

The Bruins find themselves ranked atop the Pac-12 in scoring offense, averaging 78.5 points. They have found ways to win close games against the likes of Stanford and Colorado.

Even with his team surrendering 68.1 points a game — next to last in the Pac-12 — Howland talks excitedly about running the transition and scoring after made baskets. He seems confident of this new direction.

With a smile and a clap, he said: “I’m evolving.”

But with the strongest portion of the conference schedule to come, he has been devoting more and more practice time to defense.

So who, exactly, is Ben Howland?

A defensive grinder or an offensive convert? A tough guy or a coach who seems lighter and happier, emerging from a difficult stretch?

None of these questions interest him much.

“I’m just worried about winning our next game,” he said. “It’s all about your next game.”

twitter.com/LATimesWharton

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.