Controversies such as ‘Deflategate’ aren’t new to the Super Bowl

The New England Patriots got out of the Northeast on Monday before the blizzard hit, and flew directly into the eye of a different storm.

While football fans from every corner of the map have already grown weary of “Deflategate,” New England coaches and players are nonetheless bracing for a week’s worth of questions about what they knew about deflated footballs in the AFC championship game.

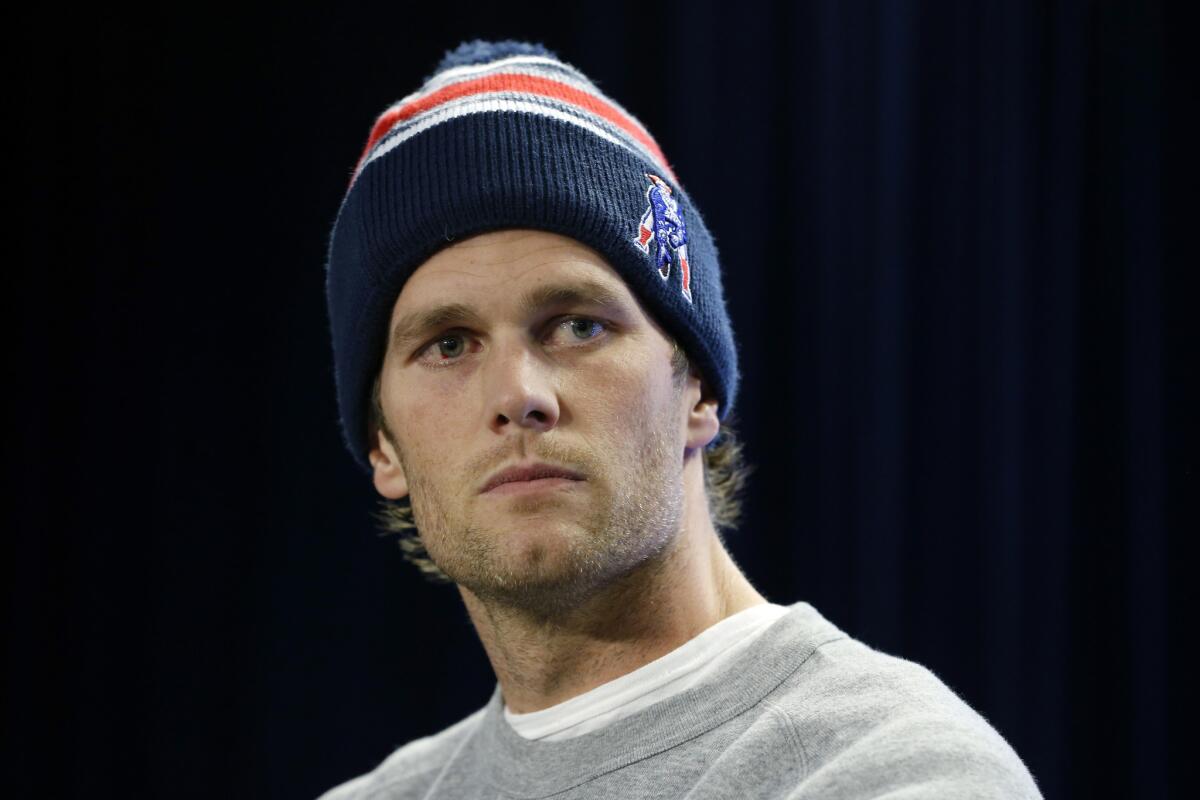

Before a send-off rally in Boston, quarterback Tom Brady tried to put the controversy behind him during his Monday radio show on WEEI.

“I personalized a lot of things and thought this was all about me and my feelings got hurt, and then I moved past it because it’s not serving me,” Brady said. “I think what’s serving me is to try to prepare for the game ahead, and I’ll deal with whatever happens later. I’ll have my opportunity to try to figure out what happened and figure out a theory like everyone else is trying to do. But this isn’t the time for that.”

Although Patriots Coach Bill Belichick has said his team followed league rules to the letter in handling the footballs in question, a report Monday suggested something more ominous.

Fox Sports’ Jay Glazer reported that the league, which is conducting an investigation into the matter, has “zeroed in” on a Patriots locker-room attendant who has already been interviewed as part of the probe.

Citing unnamed sources, Glazer said there is video showing the attendant taking the game footballs from the officials’ locker room and into another room at Gillette Stadium before bringing them out to the field. Although that in itself isn’t a smoking gun, it further raises suspicions about how closely the Patriots followed protocol and whether they had the opportunity to tamper with the footballs.

Patriots owner Robert Kraft opened the team’s media availability in Arizona on Monday evening by stridently defending Belichick and Brady, and criticizing how the NFL has handled the situation.

Kraft, reading a prepared statement, said that if the current investigation doesn’t definitively prove the Patriots tampered with the footballs, “I would expect and hope that the league would apologize to our entire team, and in particular Coach Belichick and Tom Brady for what they have had to endure this past week.”

Belichick was repeatedly asked about the situation at the news conference, and answered each by simply saying he was now focused solely on playing Seattle.

But this affair is far from the first time some type of brouhaha has cast a long shadow over the NFL’s marquee game. In the run-up to 49 Super Bowls, players have been arrested or gone missing, a different accusation of cheating was leveled against the Patriots, and a star quarterback was questioned by federal agents conducting a sports gambling probe.

Len Dawson of the Kansas City Chiefs was that quarterback, and he was interrogated during the week leading up to Super Bowl IV because of his casual connection to a known gambler who was arrested before the game carrying more than $400,000 and Dawson’s phone number.

“It was very difficult, because I hadn’t done anything wrong,” Dawson said by phone Monday. “Everybody’s yakking around trying to think of things to do or say, and I said, ‘Let’s tell the truth.’ I knew who that person was, but I hadn’t had any contact with him. It was such a disruption.”

The agents discovered quickly that Dawson was uninvolved or an Oscar-worthy actor.

“The guy says, ‘You know, I’ve interviewed a lot of murderers, thieves and all that, but I’ve never had anybody fall asleep on me while I was interviewing them,’” Dawson said. “I was tired.”

If that incident had any sort of effect on the Chiefs, it only galvanized them. They went on to beat the Minnesota Vikings, 23-7.

Other teams didn’t fare so well after dark clouds rolled in. In January 2003, the Friday before Oakland played Tampa Bay in Super Bowl XXXVII in San Diego, Raiders All-Pro center Barret Robbins stopped taking his depression medicine and crossed the Mexican border to party in Tijuana. He was unaccounted for during most of the day before the game, and was so incoherent when he returned Saturday night that Coach Bill Callahan deactivated him.

It’s impossible to know how much losing Robbins hurt the Raiders, but it certainly didn’t help. They lost, 48-21.

“It would have been better if something had happened to Barret on Monday or Tuesday before the game, as opposed to going out on Friday night and never coming back and then finding out about it on Saturday night,” said former Raiders quarterback Rich Gannon, noting the team opened the Super Bowl with an astounding 15 mental errors in the first 19 snaps.

“Here’s a Pro Bowl center and so much of our offense was predicated at the line of scrimmage. Everything was run checks and pass checks, run to pass, pass to run. ... I’d never put that on why we lost the game, but it certainly had some type of impact.”

The career of Cincinnati running back Stanley Wilson came to an abrupt end when he failed to show up for a team meeting on the eve of Super Bowl XXIII. An assistant coach found him passed out on the floor of his hotel bathroom, drug paraphernalia at his side. Wilson sat out the game, and the Bengals lost, 20-16, picked apart down the stretch by San Francisco quarterback Joe Montana.

When Oakland played Philadelphia in Super Bowl XV, legendary Raiders defensive end John Matuszak told coaches not to worry about the New Orleans nightlife. The Tooz promised to keep his teammates in line.

Apparently, he was talking conga line. He and others ignored curfew, essentially drank Bourbon Street dry, and wound up crushing the Eagles, 27-10. Because the Raiders won, the story is now part of their lore and that of the late Matuszak.

Then, there was Eugene Robinson. The day before the Atlanta Falcons played Denver in Super Bowl XXXIII, Robinson was presented with the Bart Starr Award, given to a player who best exemplifies outstanding character and leadership in the home, on the field, and in the community.

Later that night, Robinson was arrested for soliciting a prostitute.

Robinson played in the game and, perhaps distracted, made some key mistakes in the Falcons’ 34-19 loss.

Baltimore linebacker Ray Lewis played in a Super Bowl in 2001, a year after facing murder and assault charges stemming from a double homicide. (Lewis eventually pleaded guilty to a lesser charge, serving no time in prison and paying a $250,000 fine by the NFL.) The Ravens won Super Bowl XXXV, 34-7, over the New York Giants, and Lewis was selected the game’s most valuable player.

Twelve years later, the Ravens were back in the Super Bowl, and Lewis faced another controversy, an accusation in a Sports Illustrated article that he had used a deer-antler extract that contained a banned growth hormone to help him recover from a torn triceps. The Ravens won that Super Bowl, too, beating San Francisco, 34-31.

Seven years ago, the day before the 18-0 Patriots played the Giants in Super Bowl XLII — in the same stadium where New England will play Seattle on Sunday — the Boston Herald dropped a bombshell. The newspaper, citing an unnamed source, said the Patriots had secretly filmed the St. Louis Rams’ walk-through practice before the Super Bowl six years earlier. (The Patriots won that game.) Belichick denied the allegation, and the Herald retracted the story.

It’s impossible to measure whether that had any effect on the Patriots losing to the Giants, and watching their bid for a perfect season go poof.

In short, there’s no clear pattern of a team winning or losing when engulfed in a controversy during Super Bowl week.

“Anytime you have a distraction and you don’t handle it, it can become a real problem for your football team,” Gannon said. “My sense [in the Patriots’ case], this isn’t a team issue. This affects two people, the head coach and the quarterback. They’re the ones that have had to be out in front of it. They may use it as a rallying cry.

“If they play well, people will say it’s not an issue. If they don’t play well, people say it was a big distraction that led up to it and a big reason why they didn’t get it done.”

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.